eBook - ePub

Hebrews (Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture)

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hebrews (Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture)

About this book

Examine the New Testament from within the living tradition of the Catholic Church

Well-respected New Testament scholar and popular speaker Mary Healy unpacks the Letter to the Hebrews, making its difficult and puzzling passages accessible to all.

Healy's commentary shows how Hebrews reveals the meaning of Christ's death in light of the Old Testament figures, rites, and sacrifices that foreshadowed it. Healy explains that Hebrews, when fully understood, transforms our understanding of who God is, what he has done for us, and how we are to live as Christians today.

The CCSS relates Scripture to Christian life today, is faithfully Catholic, and is supplemented by features designed to help pastoral ministers, lay readers, and students better comprehend the Bible and use it more effectively.

Commentary features include:

● Biblical text from the New American Bible, Revised Edition (NABRE)

● References to the Catechism, the Lectionary, and related biblical texts

● Theological insights from Church fathers, saints, and popes

● Reflection and application sections for daily Christian living

● Suggested resources and an index of pastoral subjects

Attractively packaged and accessibly written, the CCSS aims to help readers understand their faith more deeply, nourish their spiritual life, and share the good news with others.

Well-respected New Testament scholar and popular speaker Mary Healy unpacks the Letter to the Hebrews, making its difficult and puzzling passages accessible to all.

Healy's commentary shows how Hebrews reveals the meaning of Christ's death in light of the Old Testament figures, rites, and sacrifices that foreshadowed it. Healy explains that Hebrews, when fully understood, transforms our understanding of who God is, what he has done for us, and how we are to live as Christians today.

The CCSS relates Scripture to Christian life today, is faithfully Catholic, and is supplemented by features designed to help pastoral ministers, lay readers, and students better comprehend the Bible and use it more effectively.

Commentary features include:

● Biblical text from the New American Bible, Revised Edition (NABRE)

● References to the Catechism, the Lectionary, and related biblical texts

● Theological insights from Church fathers, saints, and popes

● Reflection and application sections for daily Christian living

● Suggested resources and an index of pastoral subjects

Attractively packaged and accessibly written, the CCSS aims to help readers understand their faith more deeply, nourish their spiritual life, and share the good news with others.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

God’s Answer to the Problem of Sin

Hebrews 9:1–28

All human cultures around the world and throughout history, diverse as they are, attempt in one way or another to deal with the problem of sin. There seems to be a near-universal recognition that sin—wrongdoing against God or others—requires some form of †atonement. The evil deeds that result from human selfishness, greed, lust, jealousy, or vengeance, and the harm they cause, cannot be adequately addressed by simply making an apology and moving on. The damage must be undone, the debt must be paid, the relationship must be healed. If this is true of offenses against human beings, all the more is it true of offenses against God.

Hebrews 9–10, continuing the central argument of the letter (chapters 8–10), presents God’s answer to the problem of sin. Here the author summarizes the heart of the good news: in Christ, God has dealt with sin once and for all—not by a divine decree that simply wipes it off the ledger, but by providing the all-sufficient †sacrifice that atones for sin, purifies the human heart, and repairs the broken relationship between God and man.

Chapter 9 explains how the sacrificial system of Israel, temporary and imperfect as it was, was designed to point forward to that one perfect sacrifice of Christ. Those former rites impressed upon God’s people profound truths about the gravity of sin and how God provides atonement for it. In biblical terms, the old covenant sacrifices are †types—signs that point in a veiled way toward the culmination of God’s plan in Christ. Hebrews 9 shows, first, why those rites could never fully resolve the problem of sin (9:1–10). It then explains how Christ’s blood, in contrast, is totally efficacious (9:11–14); how the covenant has been renewed and fulfilled (9:15–22); and how Christ’s work of atonement has been accomplished in the true, heavenly sanctuary (9:23–28).

This part of Hebrews is theologically rich but far from easy reading, alluding as it does to Israelite rituals that may at first seem strange or irrelevant. But readers who patiently engage with the biblical text will be rewarded by a far deeper understanding of Christ’s sacrifice for our redemption.

The Powerless Rites of the Old Covenant (9:1–10)

1Now [even] the first covenant had regulations for worship and an earthly sanctuary. 2For a tabernacle was constructed, the outer one, in which were the lampstand, the table, and the bread of offering; this is called the Holy Place. 3Behind the second veil was the tabernacle called the Holy of Holies, 4in which were the gold altar of incense and the ark of the covenant entirely covered with gold. In it were the gold jar containing the manna, the staff of Aaron that had sprouted, and the tablets of the covenant. 5Above it were the cherubim of glory overshadowing the place of expiation. Now is not the time to speak of these in detail.

6With these arrangements for worship, the priests, in performing their service, go into the outer tabernacle repeatedly, 7but the high priest alone goes into the inner one once a year, not without blood that he offers for himself and for the sins of the people. 8In this way the holy Spirit shows that the way into the sanctuary had not yet been revealed while the outer tabernacle still had its place. 9This is a symbol of the present time, in which gifts and sacrifices are offered that cannot perfect the worshiper in conscience 10but only in matters of food and drink and various ritual washings: regulations concerning the flesh, imposed until the time of the new order.

OT: Exod 16:33–34; 25–26; 30; Lev 16; Num 17:23; Mic 6:7

NT: Mark 7:3–4; Luke 1:8–11; Rom 3:25; Heb 10:19–20

Catechism: high priest of Israel and Holy of Holies, 433; Day of Atonement, 578; Jesus and the temple, 583–86; priests of the new covenant, 1564

Hebrews 9 returns to the theme of Israel’s †sanctuary and worship, which was the topic of 8:1–6. The long quotation from Jeremiah about the new covenant (8:7–13) may have seemed a sidetrack, but it was not, since covenant and worship go hand in hand (see 7:12). One of the primary purposes of the covenant is to stipulate how, when, and where the people will celebrate the †liturgy, their public worship. And the liturgy, in turn, is the highest expression of the covenant relationship.1 A new covenant, therefore, implies that there is a new liturgy.

To set the stage for the contrast with Christ, Hebrews first describes the old covenant sanctuary, its furnishings and rites. This description depicts neither the first temple, built by Solomon and destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BC, nor the second temple, built in 515 BC and probably still standing at the time Hebrews was written.2 Rather, it depicts the precursor to the temple, the †tabernacle or tent-sanctuary that was Israel’s place of worship during the desert wanderings. This is probably because the Scripture passages that most fully set forth God’s instructions for worship are the parts of Exodus that describe the tabernacle. During Israel’s sojourn at Mount Sinai, God gave Moses elaborately detailed instructions for building the tabernacle (Exod 25–31), which Moses then carried out to the letter (Exod 35–40).

After briefly recalling these details (vv. 1–5), Hebrews notes that the very structure of the tabernacle hinted at its own incompleteness and pointed forward to something better (vv. 6–10).

[9:1]

Even the first covenant had regulations for worship and an earthly sanctuary. The Greek word for “earthly” (kosmikos) could be translated “worldly” or “of this world,” and it implies that this sanctuary could never bring people into true communion with God, who dwells in heaven. But the sanctuary was also “worldly” or “cosmic” in another sense: in ancient Israel, the sanctuary was considered a microcosm of the whole created universe. The architecture and features of the tabernacle (and later, the temple) were designed to symbolize the cosmos—the heavens and the earth, the sea, the sun, moon, and stars—and to remind the worshipers that God intended all creation to be one great temple in which all creatures would glorify God.3

[9:2]

Although Hebrews seems to refer to two tabernacles (or tents), there was actually one tent with two rooms: the outer one, . . . called the Holy Place,4 and the inner room, the †Holy of Holies. The †Holy Place was entered through a veil, and the Holy of Holies was curtained off by a second veil, made of precious fabric and embroidered with images of cherubim (Exod 26:31–33). This arrangement, along with the courtyard that surrounded the tent, created zones of restricted access. The Levites served in the courtyard, but only the priests could enter the tent itself, and only the high priest could enter the Holy of Holies (Lev 16). Even the area immediately outside the court was off limits to ordinary Israelites (Num 1:51–53). Although the purpose of the tent was to serve as a meeting place between God and his people, at the same time these zones served to instill a profound awareness of the abyss that separated humanity from the transcendent, holy God.

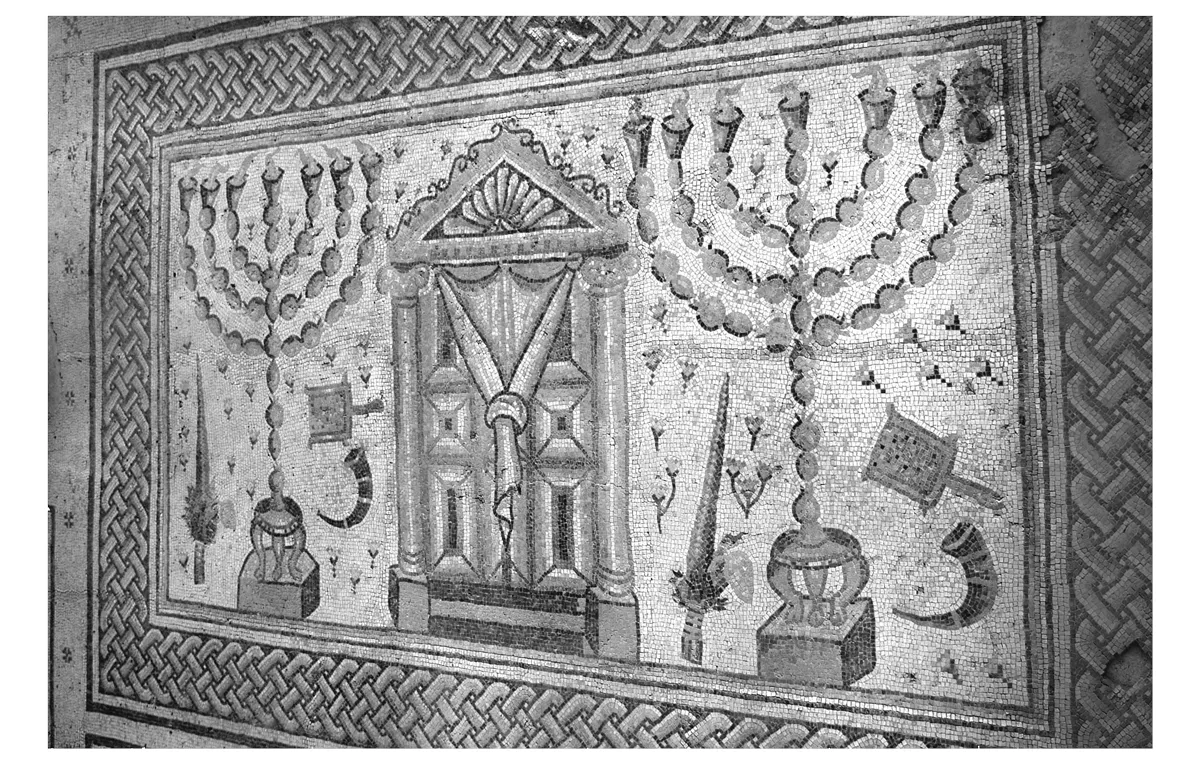

Fig. 12. Floor mosaic in the fourth-century AD synagogue in Hammat Tiberias, Israel. In the center is the curtained “ark” that held Torah scrolls. On either side are a seven-branched menorah, a shofar (ram’s horn), an incense pan, and a palm frond and citron used during the Feast of Booths. [© Baker Publishing Group and Dr. James C. Martin]

In the Holy Place were three sacred objects. First was the seven-branched lampstand, or menorah, made of pure gold (Exod 25:31–40)—to this day a famous symbol of Judaism. Each branch held an oil lamp, with cups shaped like almond blossoms for holding the oil. The menorah was to be kept perpetually lit as a sign of the Lord’s abiding presence with his people (Lev 24:2–4). With its blazing blossoms, the menorah was probably designed to evoke the burning bush where God had first spoken to Moses and revealed his holy name (Exod 3).

Second, there was the table made of acacia wood overlaid with gold (Exod 25:23–30), on which was placed the bread of offering (in Hebrew, “bread of the Presence,” or translated more literally, “bread of the Face”). These were twelve loaves representing the twelve tribes of Israel, which were replaced with fresh loaves every sabbath (Exod 25:30; Lev 24:5–9). The table also held bowls and pitchers for libations of wine, perhaps to recall the sacred meal that concluded the covenant on Mount Sinai, when Moses and the elders of Israel “beheld the God of Israel” and ate and drank in his presence (Exod 24:9–11). For the Christian readers of Hebrews, the items on the table even more strikingly evoke the sacred banquet of the new covenant, the Eucharist, in which Christ offers the cup of salvation and the true “bread of the Presence”—the bread that is in the most literal sense God’s presence in the midst of his people.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Endorsements

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Editors’ Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Outline of Hebrews

- God’s Final Word

- Far Superior to the Angels

- A Little Lower Than the Angels

- Pilgrims and Partakers

- Rest for the People of God

- Jesus Our Great High Priest

- A Call to Maturity

- The Priesthood of Melchizedek

- The True Tabernacle and the New Covenant

- God’s Answer to the Problem of Sin

- We Have Been Sanctified Once and for All

- Confidence to Enter God’s Presence

- In Praise of Faith

- The Discipline of a Loving Father

- Pleasing Sacrifices in Day-to-Day Life

- Suggested Resources

- Glossary

- Index of Pastoral Topics

- Index of Sidebars

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hebrews (Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture) by Mary Healy, Williamson, Peter S., Healy, Mary, Peter S. Williamson,Mary Healy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Commentary. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.