This is a test

- 217 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

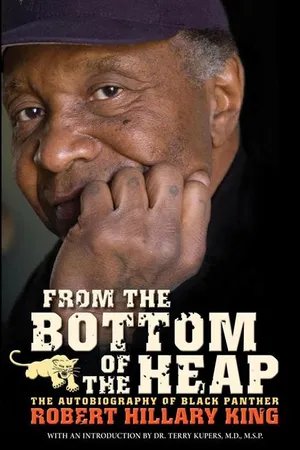

Born black and poor, King journeyed to Chicago at the age of 15. He married, had a child and briefly pursued a semi-pro boxing career. However, he was sent to prison in 1970 for 35 years for a crime he didn't commit. While incarcerated he joined the Black Panther Party and successful lobbied to improve prisoner condistions. In return, the wardens beat him, starved him and the authorities never gave him parole. This is the story of inspiration and courage and the triumph of the human spirit.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access From The Bottom Of The Heap by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Advocacy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter 1

WHEN I MET MY FATHER, HILLARY WILKERSON, for the first time I was thirteen years old. By that time, having lived an unsheltered lifestyle, I had already undergone the transition from man-child to man. But my maturity to actual manhood was to unfold more gradually. In the pages that follow, I share this unfolding with the reader.

Two young people: Male and female…a dark night, desire to escape and explore the unknown. Hormones working overtime, helped by a nip from an hidden bottle. Nine months later (more or less), on Sunday, May 30th, 1942, into this world came one Robert Hillary King — a.k.a. Robert King Wilkerson.

Hillary Wilkerson, my father — of whose seed I am the product — having experienced the joy of planting the seed, found that joy to be short-lived. In the typical fashion of many Black men of that era, he split. The responsibility for and to the product of his seed proved much more than he was willing and perhaps capable of enduring. He had to seek refuge. Hillary enlisted in the imperialist army of these United States. From there, he went on to plant seeds in other, foreign soils…

Clara Mae King, my mother, who was very young when my older sister, Mary, was conceived — and not much older at my own conception — never developed a true sense of responsibility toward any of the three children she eventually brought into this world. Years later, Clara would tell me that at the time of Mary’s birth — and mine — she felt we would fare better with her mother, Alice, than with her. My mother was very short, and her diminutive size seemed to have played a role in shaping her personality. Clara never revealed to me directly that she had hang-ups about her size, but when I came to know her years later, I could sense the insecurity that plagued her. She began drinking alcohol at a very early age, and it was alcohol that contributed to her early death at the age of forty-one.

The first-born of my mother was Mary, two years, three months and seven days my senior. Mary took after Clara in size, inheriting the gene that prevented her growth. She also began drinking heavily, and she too died young at the age of twenty-seven.

Ella Mae, my younger sister, was born a few years after me. I didn’t have the pleasure of meeting her until I was twenty-three, at my mother’s wake and funeral in 1966. And it was shortly thereafter that Mary died also…

In retrospect, when I think of my mother Clara, I am grateful that in her attempt to shield and protect me from the savage forces that confronted her, she passed me on to her own mother, Alice. My grandmother’s own standing, in many ways, was as bare as Clara’s. But my grandmother did not view me (or my sister) as being a burden. And I can truthfully say that there were many other Black women of the same era who, while facing equally (or surpassing) bad odds as Clara, met the situation head on. Alice, whom I learned to call Mama, was one such woman.

At the time of my grandmother’s acceptance of Mary and me, Ella wasn’t born. When she was, she stayed in New Orleans. Though Mary and I were born in New Orleans, during our infancy, Clara had brought us both back to Gonzales, Louisiana, where Alice lived. Ella Mae never came to Gonzales. Shortly after her birth, Clara passed her off to another relative. However, had Clara brought Ella to Gonzales as she had done with her other two children, Mama would have also been responsible for Ella’s childhood survival. That was the type of woman Mama was.

chapter 2

I HAVE SOME VIVID MEMORIES OF THE WAY Gonzales was back then. There wasn’t anything impressive about this small town and economic security was nearly non-existent, especially for Blacks. In order to feed her children, Mama worked the sugar cane fields, which was seasonal. I often heard her say, “I had to cut cane with ice on the stalks.” They grew a lot of corn there also. The town’s school was known by the simple name of “Smith’s.” I never knew the name of the school for whites. I remember Orice’s Grocery, where Mama used to “deal” (“dealing” was synonymous with having established credit). Orice’s memory is vivid because, whenever I went there with Mama, I was always treated to a “moonshine cookie,” so called because of its size and shape. My great grandparents also lived in Gonzalez, as well as some of my great uncles and cousins.

Gonzalez’s jailor, part-time handyman, and part-time janitor, was Black. According to Mama, the man who wore all of these titles was a distant cousin of ours. One day we stopped by the jail while this cousin was in the process of dining. The very first thing I noticed about him was that he had only one arm. He tried his damnedest to get me to join with him in his eats, offering me the same utensil he was eating from. I just stared at him. The truth is, I didn’t want any of that food. And the reason was, in the corner was another Black man, behind what I then described as being a “lot of skinny iron.” From behind this iron, the man watched us all, somber-like. Looking into his face, I immediately felt some kinship with him, more than with my cousin and I felt that the one-armed man was responsible for keeping the somber-looking man behind that skinny iron. The one arm, too, I found at that age to be monstrous. I disliked our cousin, and I was glad when we left.

When we had gone some distance, I asked Mama what that other man was doing at our cousin’s house, and why was he behind all that skinny iron? She told me that it wasn’t our cousin’s house, but a jailhouse, that our cousin only worked there. And she told me that the man behind the bars (not skinny iron) must have done something bad to be there. She called him a “cornvick.” I was only about four years old at the time, and my small mind went to work. It told me that since there were many cornfields around, a “cornvick” must live between the stalks and was considered “bad” for doing so.

I was glad we lived in a house. It was an old, decrepit house, just off of the highway. It was shabby, unpainted, and leaky; whenever it rained, that old house rained also. The summers weren’t too bad, our house had lots of holes in it which served as air ducts. But the winters, even in Louisiana, were bitterly cold. At that time, Mama had nine living children of her own: Clara, my birth mother, was the eldest; Robert and Ruth were fraternal twins; Houston was next in line. Then there were George, Henry, William, Verna Mae, and James. By the time I made my fifth birthday, Clara, Robert, Ruth, Houston, George, and Henry (whom Mama had called her “first set of children”) had all gone their respective ways, some leaving as young as thirteen years old. That left William, Verna Mae, James, Mary and me, and of course, Mama.

One bright summer evening, before Houston and George departed, I remember standing in our yard, looking across the street at the well-painted houses with manicured lawns inhabited by whites. I saw some activity in one of those yards. Looking closer, I saw two of my uncles, Houston and George, in a row of pear trees, loaded with ripened fruits. Houston and George were violently shaking the trees, while nearby a dog barked incessantly. When they would get through shaking one tree, they would rush to another, repeating the effort.

After doing this a number of times, they began picking the fallen pears from the ground and throwing them across the street, into our yard. Everywhere I looked, it seemed to be raining fruit. I wanted desperately to pick one up and eat it, but each time I attempted this, falling pears would barely miss my head. I began to dart from place to place, but everywhere I darted, more pears fell. Soon the thought of trying to get a pear left me. I was now desperate for some shelter. I tried to make it to the porch and into the house for safety, but the falling pears cut me off. So I just stood there, rooted in one place, and began to holler, louder and louder. I think my loud bellowing actually scared my uncles. I know for sure that it got their attention. They stopped throwing and began gesturing wildly for one of the other children to usher me to safety.

When George and Houston returned from that escapade, we all had a big laugh. It was not long after this incident that George and Houston departed from us, only to be seen again years down the road.

With the departure of Houston and George and with Mama working six days a week, the responsibility to watch us when Mama wasn’t home fell to William, the next oldest. Each day after Mama left for work, we would find ourselves plagued by a huge German shepherd dog that belonged to one of the whites living across the street. That dog knew we were alone, and that we were afraid of it. We would all be out in the yard playing, and one of the children would see it coming and yell, “Here comes the dog, git on the roof!” That was the safest place to hide from the dog when Mama wasn’t around. We had to shinny up a post to get to the roof, and as the littlest, I was always last. William would always be the one to reach down and pull me to safety.

One day everyone was too busy playing to keep much of an eye out for the dog. By the time we spotted the animal, it had advanced too near. Everyone broke into a dead run straight for the porch. First William, then Verna, now Mary, then James. By the time James had shinnied up the post, the shepherd was on the porch, snarling and baring its fangs. I tried to wrap my little legs around the post, at the same time reaching toward William, who was yelling for me to grasp his outstretched hand. At one point, William had me in his grasp. But then I slipped: I fell hard.

Thinking only of the dog, I immediately sprang to my feet, turning around to face it. By this time, it was right upon me. I was trapped and I wasn’t expecting any help from William or any of the rest of them. They had proven time and time again that they were not going to tackle that dog, and neither was I! Trapped and frightened, I began to yell bloody murder. Then a strange, but wonderful, thing happened. The dog stopped in its tracks. It gave me a most curious look, dropped its tail between its legs, and hauled ass away from the premises, and didn’t look back until it had reached the other side of the highway.

From that day on, I cannot recall our having any further trouble with that dog. Once more, my holler had come to my rescue!

chapter 3

WILLIAM HAD LEARNED THE RUDIMENTS OF cooking, but sometimes we had nothing. On these days, we had to wait until Mama came home. We all found consolation in sight of her coming up the highway, grocery bags in arms.

On one of those days, knowing that we all were hungry, she headed straight to the kitchen to prepare a meal. I was right behind her, holding onto her skirt. Every now and then she would reach down to cuddle me, saying, “Don’t worry, baby, mama gon’ feed you in a little while.” And I was believing this, too. I really thought it would only be a “little while.” But a “little while” turned into a “huge-while” that to a kid could seem like forever. Every now and then Mama would lift a lid from one of the pots, and the smell escaping would assault me with such intensity that I would bend over, holding my arm across my empty belly. Each time she would do it, Mama would say, “Just a little longer, children,” or something to that effect. Finally I could stand it no longer. She lifted a lid from one of the pots, and before she could say a word my belly growled in protest, and I followed suit: I started hollering and bellowing and didn’t stop until she knelt down and took me in her arms. It was this soul-searing yelling and bellowing that made Mama realize how truly hungry I was. She said, “Oh, my poor baby!” The rice was already done. The meats in the pots were not quite done, but the gravy was. I eagerly ate rice and gravy…

I have related these childhood incidents because I feel there is a present-day application that can be drawn from them. The application is: when one has a legitimate beef, a loud protest is the correct behavior.

Later I remember a deluge: Water — seemingly with a desire for retribution — literally poured from the sky. And the water rose. More than three feet high, it covered our porch and beyond. Inside the house the water was nearly up to my knees; off the porch, the water would be over my head.

The morning after the rain ceased, Mama had to wade in water up to her waist in order to get to the highway so she could proceed to work. The land on our side of the highway was much lower than the other side, where the whites lived.

Before Mama left that morning, she told William to keep us all inside, and for him to stay there too. But as soon as Mama was out of sight, William was heading for the porch. We all followed him. I stopped in the middle of the porch, for William told me to stay where I was. He and the others went splashing off into the yard. Watching them play, I felt alone, and the farther away they waded, the more alone I felt. I began to inch my way towards the end of the porch. I really didn’t intend to go off the porch, but with my eyes trained on their retreating forms, the spell was cast. Each time they would take a step, I would take one. The water did the rest. It was polite enough to pull me right off the edge of the porch. This is one time my yelling failed me. I tried, but nothing, not a sound would escape from my mouth. Then, from what seemed like a mile away, I heard Mary yelling: “Oh look! Junior is drowning, Junior is drowning.” They all hurried back as fast as they could, and pulled me to safety. I was numb with fear, but most grateful. I remember hearing William say: “We ain’t goin tell Mama about this, ya’ll hear?”

Mama never found out.

A few days later — the water now receded — we were out playing once more. We spotted a big fat field rat. William decided to tackle it. He found a stick, and advanced upon the creature, backing it into a corner. Having no place to turn, the rat went on the offensive. It leapt up and caught one of William’s fingers, biting down viciously. Surprisingly, William didn’t scream. Instead, he seized the rat by the throat, and choked it to death. When he pried its mouth open his finger looked as if it had been torn by a pair of pliers.

We all went back to the house, bringing the dead rat with us. William poured coal oil on his wounded finger, which stopped the bleeding. Then he found a spider-web and wrapped it around his finger. He poured more coal oil on the web and finger, and wrapped a clean rag around it. The finger seemed to take no time to heal….

As for the rat, well…after dressing his finger, William put on a pot of water to boil. While the water was boiling, he reached for a kitchen knife and handed it to Verna, who gutted and cleaned the rat. The boiling water was used to make a rat stew, which we obligingly ate for lunch. After that day, William became somewhat of a hero to me, someone I could look up to. I was four years old at the time.

With school beginning, and the rest of the children away, Mama would bring me to her parents’ house, and they would mind me while she worked.

Alice’s parents, Robert and Mary Larks, were my great grandparents, whom I addressed as “grandpa” and “grandma.” I am told that they had a total of twelve children, but in my lifetime I’ve only met seven: Norsey and Morris were the males; Carrie, Alice, Clementine, Alma and Alka were the females.

With all of their children grown and gone, grandpa and grandma had lots of free time, and in their leisure, they were glad to have me around. But they were also to be feared at all times. Whenever either of them spoke, it seemed like a command. I stood in awe of both.

I am told that they both were part African and part “Indian,” that is, Native-American. Her form of disciplining was the pulling of the ears, his was the traditional “strop,” as he called it. I tried to steer clear, always, of grandpa’s “strop.” Neither Grandpa nor Grandma was mean or anything of the sort. They were just two people who tolerated no nonsense.

I remember once Grandpa and I were in his garden, hoeing the plants. Actually, Grandpa was doing the hoeing. Every now and then I would make an attempt at it, but the hoe I was trying to use wouldn’t let me. If the hoe wasn’t falling from my hands, I was falling to the ground in my attempt at hoeing! Each time this would happen, Grandpa would throw back his head and roar with laughter.

Around noontime, we left the garden and headed to the house for lunch. Grandma was out visiting at the time, so Grandpa opened the china cabinet, removed a deep dish, and began filling it with good smelling food. Thinking it was my food, I was ready to sit and eat. But Grandpa sat at the table and began to eat all by himself instead. I stood there watching him all the while, wondering just when he would fix mine. When Grandpa had eaten all but a little of the food, he got up, nudged me to his chair, and told me to eat the rest. I sat eagerly and ate what was left.

That evening Mama came and picked me up. She asked me, “What did you and papa do today?” I told her that we had worked in his garden, and that afterwards, Grandpa had gone into the house and fixed himself a great big plate of food. I motioned with my arms to show what a great big plate of food it was. Mama asked “Well, did he fix you one too?” I said, “No, Mama, he didn’t fix me no plate.”

Mama was really asking if had I eaten that day. But at the time, my child’s rationale could not understand this. I answered directly, and what I thought to be correctly. Grandpa hadn’t fixed me a dish when he had fixed his own. But the way it came out, Mama believed that Grandpa hadn’t fed me at all.

The next day, when Mama dropped me off at Grandpa’s, she turned to him and went into an unexpected tirade. “My baby tells me that y’all worked in the garden yesterday and afterwards, y’all went into the house and fixed you food, bu...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- DEDICATION

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- A WORD

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER 1

- CHAPTER 2

- CHAPTER 3

- CHAPTER 4

- CHAPTER 5

- CHAPTER 6

- CHAPTER 7

- CHAPTER 8

- CHAPTER 9

- CHAPTER 10

- CHAPTER 11

- CHAPTER 12

- PHOTOGRAPHS

- CHAPTER 13

- CHAPTER 14

- CHAPTER 15

- CHAPTER 16

- CHAPTER 17

- CHAPTER 18

- CHAPTER 19

- CHAPTER 20

- CHAPTER 21

- CHAPTER 22

- CHAPTER 23

- CHAPTER 24

- APPENDICES

- KING FAMILY TREE

- ANITA RODDICK A FRIEND OF DISTINCTION

- A POEM FOR ALICE (AFRICA)

- MALIK RAHIM AND THE FOUNDING OF COMMON GROUND

- THE CASE OF THE ANGOLA 3