![]()

1

Vermouth

Most people who drink cocktails have sampled vermouth, often without being aware of it, and usually without even knowing what vermouth is. Vermouth can be red or white, sweet or dry. Announcing itself with fragrances of spices and herbs, vermouth is known for its exotic and pleasing aromas, and its interplay of bitter and sweet components on the palate.

In fact this is the definition of vermouth: an aromatized, fortified wine. And this is what has galvanized the mixology world in recent years: the rediscovery of a wine that adds unusual dry or sweet elements to a cocktail, blending beautifully with a variety of spirits, bitters and citrus accents, making it easy to create perfect balance in a glass.

Vermouth Before Cocktails

Was vermouth created as a cocktail element? Absolutely not. In the eighteenth century, when vermouth became popular in Europe, there was no cocktail movement in existence. There was no tradition of blending finished wines and spirits. Lacking the modern transportation network we have today, Europeans in every region were limited to consuming their own locally produced drink. Sometimes it was simply wine from local vineyards, or it could be a marc or grappa-style beverage: a strong alcoholic drink made with fruit pomace (the remains after grapes have been pressed for wine). Sometimes it was a distilled spirit – a brandy made from grapes or whatever other fruit or grain grew locally.

Vermouth was a new development in the 1700s in Torino (the city now known to English-speakers as Turin), Italy. It was a wine that was fortified with alcohol and aromatized with many herbs and spices, but aimed at the general consumer, and not meant to be a medicinal treatment. Much as the ‘cordials’ of today were originally considered enjoyable versions of health tonics, vermouth in essence straddled the line. It was basically an aperitif, an appetite stimulant taken before the meal. This is a good rationalization for drinking vermouth, whether or not it is true.

Vermouth also became popular because people enjoyed its taste. It had a familiar flavour profile for inhabitants of this part of Piedmont (now in northern Italy), with native mountain herbs and a well-established combination of sweetness and bitterness. Sweetened, herbed wines had been in existence in Europe for centuries by the time vermouth came along. In Turin, exotic spices were also added to vermouth because this city was on a spice-trading corridor that led first from Asia to Genoa by ship, then over land through Turin to more northern European cities.

There are basically three traditional, international styles of vermouth: red, sweet white and dry white. Red is called rosso in Italian and rouge in French. It was the first style created, followed by sweet white, which is called bianco in Italian and blanc in French. Dry white is referred to as ‘dry’ or ‘extra dry’ – the English terms are used on labels in most countries. Traditional vermouth is made with white wine; red vermouth gets its hue from the herbs used for flavouring, as well as some caramelized sugar for colouring if necessary.

Many wonderful, small artisanal producers are popping up in the New World as well as in Europe today. These new companies may make vermouth in traditional styles, or with their own formulas: recipes of wines, herbs, spices and production techniques that might be quite different from historic production. Each country or region has its own rules for vermouth labelling, and some of them can be quite broad. But if new producers don’t want to be identified with a specific vermouth style from France or Italy or Spain, they don’t have to be. This can make for fascinatingly creative vermouths. However, it can also make it difficult for bartenders to create drinks with these very original products: a mixologist must sample each vermouth, and then work out his or her own cocktail formula that melds well with each one. These are the pros and cons for each producer, who must choose either a variable artisanal style, or the standardized international style.

A Note on Bitterness

Some producers, both large and small, make a version of vermouth which is actually a ‘bitter’: a distillation of a fortified wine wherein herbs are used to create an extremely bitter flavour, and the alcohol percentage is usually significantly higher than that of vermouth. ‘Bitters’ (plural) are something completely different. They are herbal infusions used by the drop, as flavourings; the most famous one is Angostura bitters.

Sometimes a ‘bitter’ becomes confused with vermouth. For instance, the well-known Italian Punt e Mes is a genuine vermouth made in Piedmont, with a larger proportion of bitter herbal flavouring. On the other hand, Barolo Chinato, which is another bitter libation also from Piedmont, is not vermouth. It is in the ‘bitter’ category, which in Italian encompasses many different liqueur-style drinks that are known as amari (amaro, singular). The difference can be in the base wine and in the amount of bitter flavouring. Barolo Chinato producers, for example, use a base of Barolo, a red wine. They also aim for more of an emphasis on the bitterness, while true vermouth is a more complex melange of flavours ranging from sweet through herbal to bitter.

Unless the production method is known – or there is clear labelling – it is easy to confuse these preparations because a bottle of bitter may look like a vermouth and it may (or may not) contain similar herbs. In Italy, for instance, each region has its own preferred traditionally made, local bitter. In fact every village in the region may have a slightly different favourite preparation.

Bitter products are most often employed as digestivos in Italy or digestifs in France, which means they are traditional, well-respected aids to digestion; they are usually taken after the meal. Vermouth is served before the meal and if anything is considered to be an appetite stimulant, not a calming drink.

It’s almost a matter of degree. But for the purposes of this book, the discussion here will be about fortified wines that self-identify as vermouth. For the reasons noted above, and because there are infinite numbers and styles of local ‘digestive’ bitters made with fortified wines and other types of alcoholic bases, this chapter will deal only with the larger categories of vermouth: red, blanc or bianco (sweet white) and extra dry (also known as dry white).

Italian and French History Intertwined

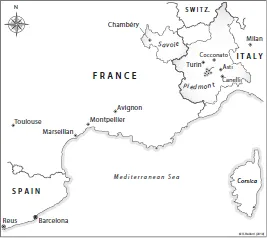

By the early 1800s vermouth’s popularity had spread from Piedmont west to the southern Alpine region of France, where it was also produced by quite a few companies. Soon afterwards it spread to Spain, which mainly produced domestically consumed vermouths. It wasn’t until about the year 2000 that vermouth began its current resurgence around the world.

But first, back to the origins of this drink. Distillation had become well known a few centuries before vermouth was created, and was popularized in Europe by the work of Arnaud de Villaneuve, who lived about AD 1240–1311. He was born in an area of Europe then dominated by the Crown of Aragon. This kingdom encompassed parts of several countries as we know them today, including southern France, southern Italy, northern and eastern Spain and the islands of Sardinia and Majorca. Villaneuve (also known as Villanova and a variety of other spellings) was famous throughout the kingdom, gaining celebrity at Montpellier and other universities where he taught and wrote about medicine and theology. Villaneuve is widely believed to be the originator of the concept of fortifying wine, using the Arab-originated process of distilling grapes, which he then added to local wine to make it stronger, mainly for medicinal purposes. Whether it was luck, skill or a combination of the two, under his ministrations Villaneuve’s most notable patients did recover from their health problems. He became a doctor to kings and popes, moving among the kingdoms of Majorca and Aragon. Prolific in scientific research and theological exploration, he wrote dozens of books on both of these subjects, at least one of which was preserved for hundreds of years in the Vatican Library, copied over and over until the invention of the printing press, when it was printed and reprinted for centuries. According to legend, Villaneuve was on his way to cure another king when his ship went down off the coast of Genoa around 1311. Luckily, his process of fortifying wine was not lost at sea.

Arnaud de Villaneuve, a doctor, philosopher and professor who lived and worked mainly in Mediterranean areas that are now part of France and Spain, is credited as producing the first medicinal distillations in Europe, around AD 1300.

These events happened in the very region where vermouth was born: in what is now southern France, northern Italy and a section of northern Spain that includes Catalonia. Shortly after the achievements of Arnaud de Villaneuve became known, winemakers began to use distilled spirits to ‘fortify’ wine – literally to make the wine stronger, so it would be more palatable after long ocean voyages when wines were exported from France, Portugal or Spain to England, the Netherlands and other countries too far north to be able to grow their own wine grapes. At the same time, herbalists and doctors were experimenting with distillation to extract medicinal elements from various plants. They could either add the herbs to the fermented grapes or grain while they were distilling them, or they could distil the herbs separately, then add them to a wine or spirit. They also created more palatable medicines by adding sweeteners and mixing the herbal extracts into wine.

In other parts of the world and centuries earlier, in China, ancient Egypt, classical Greece and Rome, a rudimentary distillation process was known, as was the popular addition of herbs and spices to wine. There is currently some debate about which culture was the first to make flavoured drinks with a base of wine or brandy, but that discussion is best left to archaeologists and ethnologists at this point. The concern here centres not on what happened thousands of years ago in different continents, but on the drink called vermouth, and when and how it came into being.

One theory of the invention of vermouth credits a sixteenth-century inhabitant of Piedmont. This man, who was named Alessio or d’Alessio, produced a locally made drink enhanced with wormwood (Wermut in German) which was similar to a popular medicinal wine in Germany. Alessio had apparently learned about this wine while visiting Bavaria, and brought the concept back to Piedmont. His beverage was not necessarily a fortified wine, and it was taken as a medicine. However, a modern U.S. company, Tempus Fugit Spirits, now produces several vermouths with the brand name Alessio in tribute to this historical figure.

Whether or not Alessio contributed to its invention, today we would still say that vermouth is from Italy, and specifically from the city of Turin in Piedmont. So it’s not a coincidence that Turin is also currently a centre for the European commercial revival of vermouth. This Italian city remains the spiritual, and actual, home of vermouth – even though the countries we now know as France and Italy did not have the same borders a few hundred years ago. At the time that vermouth was first popularized, Turin was part of the Kingdom of Savoy, which encompassed the southeastern part of France now known as Savoie, as well as the northwestern region of Italy that is now called Piedmont. Beginning in 1416, the dukes who ruled Savoy maintained Chambéry (which is now in France) as their capital city. In 1563 they shifted the capital to Turin.

In the early 1700s the Savoyard dukes also became rulers of the Kingdom of Sardinia. Through various conflicts and treaties, the province of Savoy itself became part of France for a while (1792–1815), but the Savoy kings consolidated their power and won it back. Then Savoy was deeded to France in 1860 when the Kingdom of Sardinia became part of the newly unified country of Italy. A ruler of the Kingdom of Sardinia, Victor Emmanuel ii, was the first ruler of Italy; in fact he was instrumental in brokering the unification.

As it happens, a Savoyard king is also considered directly responsible for the popularity of vermouth; this was Victor Emmanuel ii’s father, King Carlo Alberto, in 1840. At that point in time, vermouth had become such a popular drink that the local producers deemed it necessary to arrange the protection of a king to keep it authentic. But before that, someone had to actually invent the fashionable Italian drink called vermouth.

Currently, prevalent belief – buoyed by the Carpano vermouth company today – is that the inventor of modern vermouth was Antonio Benedetto Carpano. He came from a rural area in northeast Piedmont so of course he would have been familiar with regional mountain herbs and herbal drinks. Carpano went to Turin seeking work, and found a job as an assistant in a wine shop in the centre of Turin, a shop owned by a man named Marendazzo.

The shop was located in a central plaza that is now...