![]()

1

An Orphan and a Dreamer

My ambition is prevalent that I contemn the groveling and condition of a clerk or the like to which my fortune condemns me and I would willingly risk my life though not my character to exalt my station.

—Alexander Hamilton

Alex Hamilton was born in 1755 in Charleston on the island of Nevis in the British West Indies, a place of lush tropical jungles and sugar plantations. The island was only five miles across, surrounded by the sparkling turquoise waters of the Caribbean. Pirates swarmed the nearby seas. As a young boy, Alex would have seen captured pirates hauled through town to the courthouse for judgment before being hanged at Gallows Bay. He would have seen slaves brutally whipped in the open markets and sold in the auction blocks at Market Shop and Crosses Alley. He would have seen trading ships from all over the world sail into Charleston’s port.

He lived with his parents and his brother, James, who was two years older, in a humble stone house on the main street in Charleston, within sight of the beach. His father, James Hamilton, was something of a drifter. James was a younger son of a Scottish landowner whose family traced its lineage to the fourteenth century. The Hamiltons’ ancestral home, a castle called the Grange, was located in Kilmarnock, Scotland. James came to the sugar islands to make his fortune. Getting started in the sugar trade was difficult, and unfortunately, James Hamilton had no head for business. Before long, he fell into debt.

Lacking the money for boat passage back to Scotland, he spent a few years in and out of jobs. He was working at the port when he met Rachel Fawcett, Alex’s mother. Her father was a French Huguenot who had been driven from France because of his religion, and her mother was an Englishwoman. For a while, they had prospered, even owning a small sugar plantation in the foothills, before losing almost everything when a drought killed off a year’s worth of crops.

Alex was slender, with reddish-brown hair, dark blue eyes, and the kind of pale, translucent skin that flushes easily. He never went to school. He learned French from his mother, and probably how to read and write from her as well. He was also tutored by an elderly Jewish woman, who taught him, among other things, to recite the Ten Commandments in Hebrew when he was still so young that he had to stand on a table to be by her side.

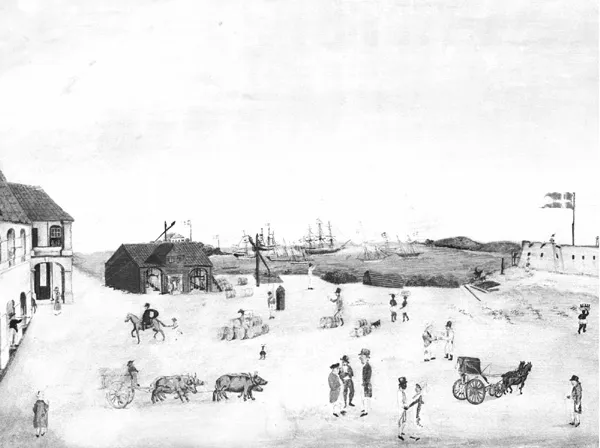

The Port of Christiansted, in the mid-eighteenth century, by H. G. Beenfeldt. This was the main port of St. Croix during Alexander Hamilton’s childhood.

When Alex was nine, his father’s brother in Scotland developed ties to a West Indian shipping company and was able to arrange a job for Alex’s father. To take this new position, James Hamilton moved his family to the bustling seaport town of Christiansted on the larger island of St. Croix, a town consisting of warehouses, stores, shipping posts, a church, and a fort that was used as a prison.

After arriving in Christiansted, Alex learned that his mother had a secret: She was married to another man. On Nevis, his mother had been able to pass herself off as Mrs. Hamilton. That was no longer possible after the family moved because it was on St. Croix that Rachel had been married to someone else—and imprisoned.

Rachel was a girl of sixteen when she married John Michael Lavien, who was about thirty at the time. She didn’t want to marry him but gave in to the urging of her mother, who mistakenly believed that Lavien was a man of wealth. In fact, Lavien was the opposite; he peddled dry goods, hoping to advance himself into the planter class. He wanted to marry Rachel because at that time, her family still owned the small plantation.

Rachel came to hate her husband, who Alex later described as crude and overbearing. A year after they were married, they had a child, Peter. After a bitter falling-out, Lavien publicly accused Rachel of having affairs with other men and had her imprisoned for several months, thinking that imprisonment would turn her into the meek and obedient wife he wanted. When she was released from prison, instead of returning to her husband, she fled to Nevis, where she met Alex’s father. By the time she returned to St. Croix with James Hamilton and their two sons, her oldest child, Peter, who was then about nineteen years old, had gone to live in South Carolina. Lavien had moved to the other side of the island, from Christiansted to Frederiksted.

About a year after Alex and his family moved to St. Croix, Alex’s father scored his first business success: He managed to collect a large debt owed to the company he worked for. Shortly afterward, he deserted his family forever, leaving Rachel to care for their two boys.

He went to the nearby island of St. Kitts. Soon the money he’d earned was gone. He drifted farther south, where he lived out the rest of his life in poverty. Alex’s view of his father was that he was lazy and not particularly competent, and that he deserted his family because he knew he could not support them. Over the years, Alex and his father occasionally exchanged letters, and later Alex offered him money, but they never saw each other again.

Society was highly stratified in the West Indies during Alex’s youth. At the top were the wealthy planters, who carried themselves like European aristocrats, riding through town in fancy carriages and wearing expensive clothing, while back home on their plantations, hundreds of enslaved people toiled in the cane-brakes—often naked—in the blistering hot sun. Just below the wealthy planters on the social hierarchy came the successful merchants and traders. Then came the craftsmen and laborers. Alex and his family were near the bottom of the hierarchy, just above the pickpockets, thieves, and drifters who roamed the streets of Christiansted. His status as a child born outside of marriage—declared illegitimate—whose father had abandoned him bumped him even further down the social ladder. His illegitimacy became a lifelong source of embarrassment.

After Alex’s father left, Rachel rented a two-story house at 36 Company Street from a New York merchant, Nicholas Cruger, and opened a store on the ground floor. She kept her accounts in order and made all payments in a timely manner. The profits from her store enabled her to feed the family. From her parents, Rachel had inherited three women slaves, Flora, Rebecca, and Esther, who had four children among them. Soon she acquired two more adult female slaves and earned extra income by hiring them out.

Then came a series of tragedies. In February 1768, Rachel fell ill with a fever. About a week after she became sick, Alex came down with the same illness. Alex regained his health, but his mother didn’t. She died at nine o’clock in the evening on February 19, 1768. Shortly afterward, the court seized all her money and possessions. Because Alex and his brother, James, were illegitimate, they were not permitted to inherit anything from her.

By this time, Rachel had almost no family. Her only living relatives were her deceased sister’s husband, James Lytton, and his children, Alex’s cousins, now grown to adulthood. For a while, Lytton had been the successful owner of a small sugar plantation. He still retained some of the wealth he had earned as a planter.

The court appointed Peter Lytton, James’s son, as guardian to Alex and his brother, and held an auction to sell off Rachel’s personal possessions, including her enslaved women and their children. James Lytton bought Rachel’s books at the auction and gave them back to Alex. The proceeds from the auction were turned over to Peter Lavien, Rachel’s oldest son, who was then a twenty-two-year-old churchwarden in South Carolina. He had made the trip back to the island to claim his inheritance. He snubbed his younger half-brothers and offered them nothing.

Alex and his brother went to live with Peter Lytton. At about this time, Alex went to work as a clerk for Beekman and Cruger, the New York trading company from which his mother had purchased goods for her store. He became chums with Edward Stevens, the son of a successful merchant. The friendship would last until the end of Alex’s life.

Peter Lytton turned out to be mentally unstable. Within a few months of taking the boys into his home, he committed suicide, stabbing himself while lying in bed. His will left everything he owned to the child of his black mistress.

James Lytton died a few weeks later. Though the sugar islands were regularly plagued by a range of tropical diseases, including malaria, yellow fever, and dysentery, so many deaths in such a short time was horrifying and devastating. If all that had happened wasn’t enough of a shock, it turned out that James Lytton had revised his will a mere five days earlier . . . and he also left nothing to Alex and his brother.

Fourteen-year-old Alex and his sixteen-year-old brother now had to fend for themselves. They went separate ways. James became a carpenter’s apprentice and went to live with his new master. Alex went to live with the family of his pal Edward Stevens. It would become a pattern in his life that well-to-do, aristocratic families took to Alex, inviting them into their homes and their lives.

Not long after Alex went to live with the Stevens family, Edward, who was a year older than Alex, departed for New York to study medicine. Edward hoped to return to St. Croix and treat patients who suffered from the island’s rampant diseases. Alex, who had to work for a living, remained in Christiansted as a clerk for Beekman and Cruger.

Alex felt stung by the injustices he had suffered. He resented the law that disinherited him because his parents hadn’t been married. He hated the fact that a person’s place in society came from birthright instead of ability and hard work. Taking stock of his own life, he feared that however hard he might work and however capable he might be, he’d rise no higher than a clerk. He longed for fame. He wished for a war so he could win respect on the battlefield and become a hero—the only way he could imagine earning a high place in society through his own accomplishments. He wrote passionate poetry, and he spun fantasies of glory and greatness.

Highly intelligent and quick to learn, he advanced rapidly at Beekman and Cruger. Soon he was doing managerial and accounting work. Because sugar prices were so high in Europe, the West Indies provided four-fifths of Great Britain’s overseas wealth, far more than the thirteen North American colonies combined. Alex thus found himself working in a hub of international trade. He learned about all aspects of the shipping and trading markets. He became versed in finance and international commerce. He also learned about smugglers, and the need for a business to have access to credit. He came to understand the value of a uniform currency.

The company traded mostly in foodstuffs and dry goods, but they also handled an occasional shipment of enslaved men and women. By this time, Alex had grown to despise the slave trade, which represented everything he hated about a stratified culture in which a person’s destiny was determined by the circumstances of his or her birth.

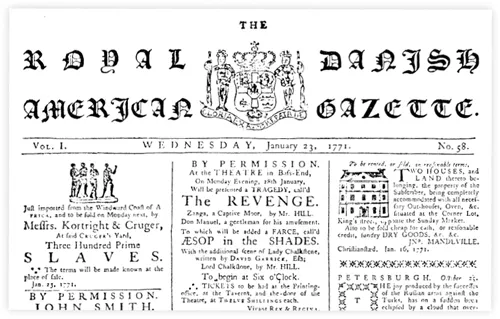

Detail of the front page of the Royal Danish American Gazette, Danish West Indies, 1771.

Alex was fifteen when the Royal Danish American Gazette began publishing a paper on the island. It included poetry. Alex wrote a love poem and sent it to the editor with a letter, which read:

I am a youth about seventeen, and consequently such an attempt as this must be presumptuous; but if, upon perusal, you think the following piece worthy of a place in your paper, by inserting it you’ll much oblige,

Your obedient servant, A.H.

While he gave his age as “about seventeen,” he had, in fact, just turned sixteen. His poem appeared in the following issue. A Presbyterian minister named Hugh Knox, whose work was also published in the Royal Danish American Gazette, was so impressed with Alex’s poem that he sought him out and befriended him. Knox made his library available to Alex and encouraged him to study.

The following year, in October 1771, Nicholas Cruger was forced to spend five months in New York because of his poor health. He designated Alex as the person to run the business in his absence—a big job for a sixteen-year-old. For five months, Alex made all the day-to-day decisions in a multinational trading firm. He collected money owed to the company. He inspected the goods and negotiated on behalf of the firm. He dealt with dishonest sea captains. He gambled on market prices. Written records and letters in his hand from this period show maturity well beyond his years. The experience fueled his dream that he was destined for something more.

On the night of August 31, 1772, came the event that would, in a roundabout way, forever change young Alex’s fortunes. That was the night a devastating hurricane struck St. Croix. For six hours, furious winds pounded the island, smashing homes, uprooting trees, tossing barrels of sugar and pieces of furniture as if they were weightless. The sea rose about twelve feet. Boats were flung onto the shore.

When the winds subsided, a shocked and dazed Alex wrote a letter to his father, describing the hurricane:

The roaring of the sea and wind, fiery meteors flying about in the air, the prodigious glare of almost perpetual lightning, the crash of the falling houses, and the ear-piercing shrieks of the distressed were sufficient to strike astonishment into Angels.

But then, Alex continued, God took mercy and relented:

He hears our prayer. The lightning ceases. The winds are appeased. The warring elements are reconciled and all things promise peace . . . Look back Oh! my soul, look back and tremble. Rejoice at thy deliverance, and humble thyself in the presence of thy deliverer.

The letter went on to describe the joy and relief—and humility—of the survivors. Alex showed the letter to Knox, who encouraged him to publish it. Alex hesitated, not wanting to capitalize on a tragedy. Knox prevailed, and the letter was published in the Royal Danish American Gazette on October 3, 1772.

Immediately Alex became a literary sensation. Even the island’s governor praised the letter and wanted to know more about the author. When the word went around that the letter was written by a motherless, illegitimate seventeen-year-old who’d received no formal education, Alex had his first taste of fame. Knox seized the moment and suggested to the island’s elite that a young man with such promise should not go to waste on ledgers and accounts. He set up a fund to collect money to send Alex to North America for a real college education. The fund provided Alex with a stipend that he would collect regularly from Beekman and Cruger’s New York offices.

Because the storm made it possible for Alex to come to the North American colonies for his education, it has been quipped tha...