![]()

1

Introduction: ‘Together We Are More’: New media for Old Tales

Victoria Grieve-Williams and Olivia Guntarik

In 1989 two Australian (NSW) policemen dressed in blackface at a police barbeque to mock two Aboriginal men who had died in custody. They wandered around with nooses on their necks saying, ‘I am Lloyd Boney’ and ‘I am David Dungay.’ Lloyd Boney had been found deceased hanging by a sock in a police cell some ninety-five minutes after his arrest in 1987. His family and the Aboriginal community and their allies believed he was one of many Aboriginal men murdered by police in similar circumstances: For example, John Pat in 1983, Eddie Murray in 1981. David Gundy too – shot dead in his home in 1989 as a result of a bungled raid by the police Special Weapons Operation Squad (SWOS) who were in pursuit of another man – is recognized by the Aboriginal community as a death in police custody. The video evidence of the police blackface mockery was passed on to an ABC reporter and televised in 1993. Later that year, eighteen-year-old Daniel Yock died as a result of police violence in Brisbane, Queensland. The evidence of the protests that followed the deaths of these men is hard to find. In recent decades, instances of Aboriginal protests and talking back to white power abound due to the widespread take-up of social media by Aboriginal people to publicize the race-hate crimes committed against them.

In 2004, large-scale riots occurred in Redfern and on Palm Island due to the deaths in custody of Thomas Hickey and Mulrunji Doomadgee, respectively. These riots were unprecedented in Australian history and succeeded in showcasing Aboriginal anger and frustration globally through media attention. Police presence in Redfern had been stepped up in what was perceived as coordinated attempts to clear the inner-city suburb of Redfern of Aboriginal people and allow gentrification to occur. Fourteen-year-old Thomas Hickey was riding his bicycle and trailed by police in a pursuit vehicle when he was impaled on top of a high picket fence as a result of being thrown into the air. Mulrunji Doomadgee was singing while walking down a street on Palm Island, taken into custody and beaten so badly that he died as a result of his liver being cleaved in two. In both locations the police intensified the riot instead of acting to calm it; in Redfern they were fighting young Aboriginal men and children. Aboriginal writer Tony Birch published an essay, ‘Who Gives a Fuck about White Society Anymore?’ as a response to the Redfern riot; media commentary was extensive. Mulrunji Doomadgee’s death has been followed by legal challenges in the courts and a documentary, The Tall Man, as well as global media publicity. The extensive use of new media and new powerful Aboriginal voices entering media commentary has arguably seen a paradigm shift in Aboriginal media profile over the past two decades.

The deaths mentioned above do not include those that have occurred through white vigilante violence, and these have added another dimension to our understanding of violent Aboriginal deaths. There are several examples. Adopted into a white family in Perth, eighteen-year-old Warren Braedon was murdered by a gang of white youths in 1993 ‘because he was black’. In 2009, Kwementyaye Ryder was kicked to death in the dry Todd River bed in Alice Springs by a group of white youth who had been driving dangerously near sleeping Aboriginal people and shouting racist insults in the early hours of the morning. In 2016, in Kalgoorlie Western Australia, fourteen-year-old Elijah Doughty was fatally wounded when struck by a vehicle that had been pursuing him on a dirt bike at high speed. The circumstances of Elijah’s death and the subsequent court hearings were widely publicized and protests were held in every capital city in an attempt to get justice for Elijah. The Black Arm Band – a group of Aboriginal musicians formed in response to a Prime Minister saying he had no time for the ‘black arm band view of Australian history’, that is, the truth telling of massacres and criminal takeover – composed a poignant song for him that is on YouTube. Aboriginal take-up of contemporary media forms has lifted protest to be broader, deeper and more effective.

In 2014, Ms Dhu, a twenty-two-year-old Aboriginal woman, called police because of a violation of a domestic violence order by her partner. Police found she had unpaid parking fines and imprisoned her for four days, deliberately ignoring her complaints of feeling unwell, wrongfully assuming she was withdrawing from drugs. She died as a result of infection caused by cracked ribs she previously suffered at the hands of her partner. In 2015, David Dungay died in prison as a result of being forcibly restrained by seriously untrained custodial officers. His inquest was shown a harrowing video of his final moments when he was saying ‘I can’t breathe’ and spitting blood. In 2017, Tanya Day died of traumatic brain injuries after she was arrested for public drunkenness on a train in central Victoria. CCTV footage shows her arriving at a police station for questioning. She repeatedly asked not to be put in custody. At the inquest into her death in 2019, police insist she was treated with dignity and respect. Her family state otherwise.

By July 2018, news of the predicament of Aboriginal Australians suffering deaths in custody and from vigilante violence had spread effectively around the world resulting in strong international support. Outside the inquest into David Dungay’s death in Sydney, Hank Newsome, president of the #BlackLivesMatter movement in Greater New York, USA, stood in solidarity with David’s family and supporters, his arm around the diminutive body of David’s mother Leetona Dungay. ‘It’s the same story, different soil’, he said in reference to the death of Eric Garner in New York City in 2014. Both men had cried out that they could not breathe when restrained by officers and, their cries ignored, had died.1

These examples demonstrate innovations in social media uses in mobilizing political support. Yet, to be too quick to celebrate social media is to ignore its ugly underbelly. Just a month earlier in June 2018, at the fringe of the city of Melbourne, more than 10,000 people had gathered in a park. On an icy winter’s night in Melbourne they had come together for a silent vigil to commemorate the life of Eurydice Dixon, a twenty-two-year-old woman who was found dead at the park the previous week, raped and murdered by a stranger on her way home from a night out in the city. The vigil was a chance for the public to come together to mourn and demonstrate the community’s desire to end violence against women. Reporters interviewed many women about why they attended these events and why they protested. Among the most heartbreaking responses a mother stated: ‘It happened to my daughter.’ For another woman it was ‘To pay respect’. For another, ‘To pray for change’. For others: ‘We want to make a difference.’ ‘We want violence against women stopped.’ Attendees held signs declaring: We will beat this. Together we are more.

This is not an unusual story. Several years earlier a candlelight vigil was held for another murder victim, Jill Meagher, only a few blocks away from this park. At the time, there was also a peace march that drew a large crowd. Bright and cheerful banners fluttered in the wind proclaiming No Violence and Respect Women.

On both these occasions political speeches about change were delivered in Parliament as a response to the acts against these women. Media attention was intense and, while the murders were deplorable and tragic, the activism and mourning in their wake powerful, astute observers were quick to point out the differences between coverage of Dixon’s murder and violence against other women, particularly women of colour.2 For instance, Chinese woman Qi Yu was killed the same week but her murder ‘slipped by with little attention’.3 The murder of Sudanese woman Natalina Angok in Melbourne in 2019 is a similar case in point. Violence against white women, particularly if they are perceived as young and ‘undeserving’, often generates more media and public attention and outrage. This phenomenon crosses global borders. It is what Cornel West referred to as ‘the problem of the color line’, tied to the practice of a long history of colonialism and white supremacy, reincarnated through the alt-right movement, through recurring acts of xenophobia, discrimination and violence against blacks, Latinos, Asians and other racial, religious, gender and sexual minorities.4

The historical legacy of white supremacy bleeds into contemporary settings perpetuated by discursive constructions that pivot between a white normative figure in duress and a wider public ready to bring redemption to the figure in crisis. We saw this in the constant media references to both Dixon and Meagher in multiple media articles on violence and women. While there is no doubt that both women deserve to be remembered, it is equally important to recognize where the gaps in the nature of the coverage lie and in the racialized textures of the stories on display. There were detailed descriptions and backstories associated with both women. Dixon was portrayed as an up-and-coming comedian with a burgeoning career, a rising star whose young life had been tragically cut short. Meagher was the newly married, independent and intelligent colleague who was at the prime of her life. Media articles describe her last movements in detail, going as far as to provide the text messages she sent to friends to reflect her wit and wisdom. There is an obvious pattern here and it highlights how the media gives voice and a face to victims of crime that is not normally attributed to the same extent for non-white women. Qi Yu, in contrast, was painted as ‘quiet’ and ‘nice’; we do not learn what she did for a living nor much about who she was besides the fact her origin is Asian. For her, there was no public vigil.

And yet the facts and figures about the rates of violence against women, Aboriginal people and other minorities reveal a sad truth. These are the statistics: One woman is killed in Australia every week. One in five women has been raped. More than four hundred Aboriginal people have died in custody since 1991.5 Violence, in all its forms, online and off, continues.

But this is not a book about statistics or data, big or small. It is not confined to any one region of the world; it is global in its reach. Neither is it a book about protests writ large.

This book is about change – in the nature of protests, in the ways in which we organize to resist and the changing repercussive consequences of different forms of protest. Our aim is to gather a range of perspectives on whether the differing ways in which people come together to work for change make a difference.

Our intention is to reveal the movement, the flows of activity that are often initiated by extraordinary individuals, the vibrancy, proximity and even distance associated with these changes. We have focused on media, communication tools and actions, as well as their associated acts of sharing, networking and influencing practices. This anthology documents and celebrates recent works and thinking, approaching change from historical, personal and political perspectives. The book can be read as offering an opportunity to understand a multifaceted, transnational phenomenon – the coming together of people to instigate change, and the modes and practices of communication that make those solidarities real.

New beginnings …

We begin with the premise that connections between older and newer forms of protests are not well understood in that there is an assumption of a disconnect, that historical forms of social and political organization were not as effective as more contemporary forms. We begin with a focus on the people at the margins who have the most to gain but also the most to lose in instances of social unrest. We begin with the claim that while social media protests are an inherent part of contemporary life, their relative efficacy to traditional protests (such as sit-ins, pamphleteering, speaker shoutdowns and obstructions) in the pre-internet age has yet to be fully explored, understood and contextualized.

For these reasons, we made a point to resist beginning with the biggest protests originating in the West, namely the United States. Instead, we privileged writings from the Global South and contributors who describe the challenges of communities and individuals who have overcome the lack of information, resources and policies specific to their needs. We centred our attention on those people who have to be more innovative in their drive for change and to advance their message. Within the pages of this collection, readers will only find passing references to Occupy Wall Street and the #MeToo movement. Our starting point for analysis is Aboriginal Australia, a place and a people that tend to go unnoticed in ever-growing discussions on social movements. Yet for us, this genesis represents the textual and contextual horizon of our approach: to position a critique of any theorization of social movements along the borders of difference and across cultural and political content that tends to be reduced, overlooked or stereotyped in popular media.

In this light, the significance and applications of visual media during protests cannot be underestimated. These images hold our attention for a reason; they possess the power to convey a larger story, to capture a moment in time, and carry the potential to take us back to an individual or collective experience of resistance. They bear the traces and frictions of the encounter between people, places and technologies, between ideas and their historical worldviews, and between those activists and communities sitting at the heart of the struggle. As visual artefacts, they also retain timeless qualities of nostalgia for what has been lost, while communicating a movement’s central purpose or appealing to our collective conscience.

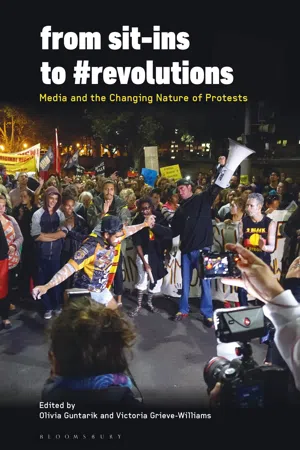

The image on the cover of this book expresses a particular history, part of the 2015 National Day of Action to protest the Australian government’s as yet unsuccessful bid (despite continuing threats) to force the people within 150 remote Aboriginal communities in Western Australia off their land. During this time, a series of gatherings and events were staged across major regional and urban centres, including Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney and Perth, organized under the banner of #SOSBlakAustralia. These protests rallied people at key sites to take over major intersections of the city. Paddy Gibson, an activist academic from the University of Technology Sydney, took this photograph during the Sydney protests as the crowds marched towards Central Station, showing how the resistance in Sydney connected to wider national action. This photograph reflects the sense of cultural pride on the day. The man holding the megaphone is Felon Mason, who had a strong leadership role in the demonstration. He used the megaphone to marshal the crowds and to direct the protest chants, which centred on the issue of community closures. Felon also guided the singing and dancing taking place at the intersections, using the megaphone to deliver short impromptu speeches along the way, while urging the people to band together to defend the autonomy of remote communities. He made a point about how the closure of the Aboriginal community in Redfern at the Block predated the push to close remote communities and this needed to be a strong focus of the campaigning in Sydney. By attacking the community in central Sydney over many years, the government had managed to remove a vital hub of black activism that had supported communities across Australia (see Chapter 2).

Paddy Gibson shared this image on his Facebook page, and the photograph was re-shared through new social networks, jostling with other images of the crowds on the day. This image of protesters who had stopped traffic as they performed an Aboriginal dance, circulated with other images of protesters holding banners that read, ‘Our Land, Our Life’; the distinctive Aboriginal flag dotting the landscape is iconic to Aboriginal protest in Australia.

In selecting this photograph as our cover image, we draw attention to the importance of images in symbolizing significant protest moments and the ways in which visual media can resonate with the people and continue to be viewed, recirculated and re-presented in different forms and new contexts. This is revealing of the ways that an image can convey mood, tone and raw emotion, how the visual elements of time and place can touch us, divide and conflict us simultaneously. Ultimately, what this photograph represents is our persistent hunger for consuming history through the image. We need the enduring power of images to reinforce our beliefs, for image and imagination are inextricably linked insofar as certain pictures of history can allow for a kind of collective imagining. The photograph of the young warriors from more than 100 years ago in Grieve-Williams’ chapter on Willie Brim (Figure 7.1 on page 96) is significant because, alongside the more recent photographs in the chapter, it highlights cultural continuity while asserting temporal depth, thus providing a way to understand how the past matters in the present and for the generations to follow.

We cannot build a better future without imagining the possibilities of our shared futures. Our opening chapter offers a discussion of Aboriginal activism in Australia as a way to consider these possibilities. Grieve-Williams highlights how Aboriginal people have fought against racial segregation policies both at home and abroad, and raised awareness about stolen Aboriginal children, slavery and stolen wages, the need for citizenship, for land rights, for self-governance and most recently the need for a treaty or treaties, as well as the threatened closure of remote Aboriginal communities through #SOSBlakAustralia. Australia has a black history and we wanted to centralize the ways in which these political claims continue to challenge and resist the colonial legacy and the development of the neoliberal state.

Chapters in this collection also privilege non-Western traditions and peoples, incorporating decolonizing alternatives that sit outside of Eurocentric positivist models. To this end, we are inspired by Patricia Hill Collins’ work on the concept of intersectionality, which insists on bringing multiple power relations and identity politics into view. Collins’ theoretical insights allow us to scrutinize how systems of domination mutually cohere along the lines of race, class, gender and nation. Here, we see our common challenges as being greater than our differences; here, we see the greatest challenge being how we express and engage with those common challenges across our differences. Collins offers a valuable perspective that prompts us to question the relations of power that shape our social conditions and the ties that bind us to different forms of oppression. Her acute awareness of the need to create safe spaces of diversity in fostering group autonomy and effective coalitions resonates with our own worldviews on the need to identify points of connection across raced and gendered cultural, political and national boundaries. We applied these considerations to ground our socio-historical approach to viewing political struggles and their multiple dimensions and intersections. This informed our thinking in gathering this collection, which personifies both contemporary and traditional cultural forms of expression, the expression of activism in reg...