![]()

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION: ETHICS, “LITERATURE,” “THE HUMAN,” AND IRONY

Wittgenstein, in the lecture discussed above, describes his “feeling” about ethics “by the metaphor, that, if a man could write a book on Ethics which really was a book on Ethics, this book would, with an explosion, destroy all the other books in the world.” Assuming he means that such a book would contradict the very notion of a book, I accept his view. It follows that I am, at the very least, reluctant to think of my own work as a book “on ethics.”

To most readers, in fact, it will look like a book on “literature.” I have reasons for disliking this term and the whole concept it tries to name, reasons I will set forth below. But it is true that mine is a book mostly about texts, as it must be. If the project of carrying ethics beyond Wittgenstein could be adequately represented in a free-standing conceptual structure, the result would be precisely a book “on ethics” and presumably an explosion. The project, accordingly, is made up mainly of finding ways to avoid this contradiction, ways of writing that have a clear ethical dimension without ever being “on ethics” in any reasonable (or explosive) sense. Nor do I mean “ways of writing” in the abstract, which would lead to the same contradiction. I mean specific texts, which I have chosen for what I hope will be their usefulness in enabling me, in my turn, to produce a text that both invokes and avoids the bedeviling contradiction of ethics.

My project, thus understood, is not new. Among philosophers and literary scholars, in fact, there has been great interest in attempting to rescue ethics by way of the attenuation it undergoes when forced into conjunction with the concept “literature.” One recent book, Martin Blumenthal-Barby’s Inconceivable Effects, starts out from the same lecture of Wittgenstein that I have cited and contains an excellent summary of recent work with an orientation similar to its own. I will use this book, further on, to situate what I am trying to do.

Ethics and Its History

But hang it all, what is ethics?—readers will ask. Given the problem of taking a position “on ethics,” I will go as far as I can in answering.

Ethics is involved in any decision I make about what to do when my conduct is not fully determined by necessity or at least practicality. And if the idea of “acting ethically” has any meaning at all, then it must be true that in acting thus, I do not simply satisfy my personal whims or desires or needs—which implies that ethics has to be understood as a method.

Ethics, in this basic sense, is not the same thing as morality. My own view is that what we normally recognize as morality is a particular type of ethics, not identical with the whole. Morality, I mean, is any ethics that has a metaphysical dimension, any ethical method that is derived from a rational ideal or perhaps from the content of a revealed religion. I do not claim that this distinction is traditional, or even etymological; mores, after all, in Latin, can designate mere customs. But “morality,” in English, does suggest something rather more elevated than “ethics,” which is the basis for my terminological distinction.

Many writers—Kant foremost among them—would insist that my distinction is vacuous, that there is no such thing as ethics without an ideal or metaphysical underpinning, that if rules of conduct are to be taken seriously, they must be given by some higher authority. (For Kant, that authority is the inherent structure of reason.) I disagree. I do not even agree that the concept of ethics necessarily includes the concept of rules. Ethics is always a method. But I deny that the manner in which my ethical conduct deviates from what I would otherwise find easiest, or most comfortable or advantageous, can always be explained by formulable rules.

Ordinarily (or Kantianly) this matter is looked at the other way round. Morality is understood as the study of duty in the broadest sense, including my duty toward myself and toward various religious and political institutions, as well as my duty in transactions with other people. Since ethics is concerned mainly with these latter transactions, it is thought to be contained within morality, which would imply that its content can be derived from moral principles. My preference, on the contrary, is to regard ethics as the more general category and morality as one particular form. Even within the scheme I propose, morality could be understood as dominant, could be considered the essence of ethics. But it does not need to be considered thus.

In any case, I insist on the character of ethics as method—an idea which I borrow from Nietzsche in a manner I will explain in the next chapter. This approach excludes from ethics, for example, Emmanuel Lévinas’s philosophy of encounter with the “other” and Martin Buber’s dialogue philosophy of the “I–Thou,” both of which play out in experience considered as a developing whole and do not originate as a methodical intervention in experience. There is plenty of room for ethical discussion in Lévinas’s thought, as in Buber’s. But ethical discussion and ethics are not the same thing; otherwise a book “on ethics” would be possible. The strict idea of method, moreover, raises the question of the specific collective, the “we,” in which this or that method is respected; for without such a collective, method is mere idiosyncrasy. Therefore the ethical “we” is crucial in my view. Ethics in the form of propositions, as far as I can see, is inescapably universalist, in the sense that its “we” is always at least universalizable. (If the propositions make sense, they are available to anyone.) The question is whether a non-propositional ethics can be found, and what sort of non-universal “we” would accompany it. The case of Habermas, whom I will discuss in detail, is instructive. His ethics is emphatically methodical, reducible to the method of rational argumentation. But, at the same time, the strength of his insistence on a universalizable collective creates an internal tension that I claim constantly unbalances his Enlightenment project.

At this point I think I have said all I can on a general plane. I do have reasons for subordinating morality to ethics, and for positing a non-universal “we” and the idea of method. But those reasons belong wholly to the domain of practical criticism. I will argue that there are many important ethical thinkers whose thought is completely misunderstood if it is taken as universalist or moral. And I will argue further that we owe precisely to these thinkers a sense of the ethical that is entirely indispensable in the world of modern politics, science, and religion, where the contradiction suggested by Wittgenstein has become endemic and increasingly corrupting.

My argument is rooted in the eighteenth century, especially with Leibniz and Lessing, who are important not only in themselves but also because of their proximity to Kant. For the ethical side of their writing has been obscured by the pretensions of what I will call propositional ethics, the type of ethics that is insisted upon by Kant and then subscribed to in most post-Kantian school philosophy. (It is the type of ethics that would cause Wittgenstein’s universal “explosion” if it could be realized.) But I do not mean that Leibniz and Lessing are ethical innovators. They are, rather, the preservers of a long tradition of non-propositional humanist ethical writing, preservers now in an increasingly inhospitable age, that age whose spirit is then captured by Kant’s prodigious propositional achievement, the categorical imperative. Kant is much more the innovator, and a very successful one. But an understanding of what Leibniz and Lessing work to preserve makes it easier for us to recognize their practice of pre-Kantian ethical writing, writing in the humanistic tradition, when it reemerges later in response to more modern problems. I will call that traditional practice rhetorical ethics (ethics embedded in a text’s rhetoric, not expressed in propositions). But rhetorical ethics must not be confused with Habermas’s “discourse ethics,” which is a prime example of the attempt to revive precisely propositional or Kantian ethics in a form supposedly purged of its difficulties.

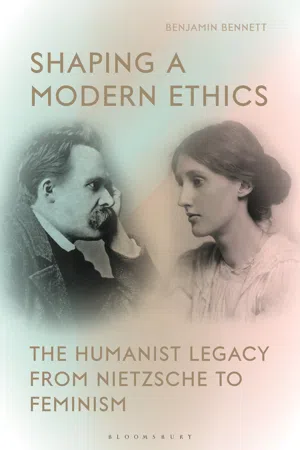

I will begin my argument in Chapter 2 with the modern form of rhetorical ethics, the “ethics of irony,” that is worked out by Nietzsche and then, so to speak, re-originated by Richard Rorty. Only after this matter is set forth will I go back to the eighteenth century and, in Chapter 3, attempt to show how Nietzsche’s achievement in ethics is anticipated by Leibniz’s non-Kantian ethical procedure—a procedure, incidentally, that is not derivable from his morality or theory of the good. Then, in Chapters 4 and 5, I will take up Lessing’s ethics of irony and discuss the manner in which it can be regarded as a Jewish ethics, interestingly similar to the ethical dimension of psychoanalysis as understood by Freud. Chapter 6 will suggest a provisional theoretical structure by situating Habermas, Rorty, and Niccolò Machiavelli with respect to some crucial issues. And finally, in Chapter 7, using texts of Virginia Woolf, Ingeborg Bachmann, and Monique Wittig, I will try to show the unique and historically inevitable operation of ironic or rhetorical ethics in feminist thought.

Ethics of Reading?

The general idea of a modern non-propositional ethics is not new. Martin Blumenthal-Barby opens his book Inconceivable Effects with a lucid summary of the literary and rhetorical aspect of ethical thinking as it evolved mainly in the twentieth century (ix–xxxi).1 Under the rubric “Philosophy’s Turn to Narrative” (xi) he discusses Alasdair MacIntyre, Richard Rorty, and Martha Nussbaum, and eventually dismisses all three: MacIntyre for his insistence on community membership as a basis for ethics (xii) and the other two for being insufficiently attentive to the “figural” or “aesthetic” or “material” component of literary texts (xiv, xxiii). I think he is not fair to Rorty on this point, especially not to Rorty’s idea of irony, which I will treat in Chapter 2. But he is certainly right when he talks about a modern awareness—I would say, the modern revival of a very old awareness—of the “insufficiency of propositional language in the face of ethics” (x).

After discussing the search for ethical orientation in responses to the content of more or less literary narratives, Blumenthal-Barby takes up the topic of “Literary Studies’ Turn to Ethics” (xviii), his main instances being Wayne Booth, Tobin Siebers, and J. Hillis Miller. Booth’s “ethical pluralism” (xix), as far as I can see, is not much different from the ethics that had been ascribed to Rorty or Nussbaum. But when we get to the matter of an ethics of reading in Hillis Miller and Siebers, or more specifically an ethics of critical reading, we find ourselves much closer to the center of the problem of a modern ethics—if not to a solution of that problem. The trouble is that we do not have a good idea of what we mean by “reading” in the first place. Is reading ever enough of an act to warrant ethical consideration and judgment? Or does it, as an act, ever have enough in the way of social or political consequences?

Blumenthal-Barby, taking a cue from Derek Attridge’s response to Hillis Miller, suggests invoking the thought of Lévinas and the idea of “the ethical demand of the other” (xxii)—except that the otherness in question is here not that of another human being but that of a literary text, a “textual otherness” (xxv, xxviii) that consists in the text’s resistance to the appropriative advances I make in reading it, its resistance to “the encompassing grasp of our interpretive techniques” (xxvii).2 This conceptual move is certainly ambitious enough, but it cannot possibly succeed if we do not find a way of regarding the reading process as an “event” (xxviii)3 in the reader’s experience, comparable to the direct encounter with another person. And here a difficulty arises—in my view a crippling difficulty. For while we cannot claim much positive knowledge about what we call “reading,” still there are some negative points about which we can be fairly definite. And one of them is that “reading,” in any reasonable sense, does not have the quality of an experienced “event,” for the simple reason that it cannot be located in time. An event, by definition, is chronologically locatable, whereas (as Stanley Corngold points out) every instance of reading is automatically un-located in experienced time by the components of pre-reading and re-reading that belong to its very constitution.4

Perhaps what we should really be talking about is not an ethics of reading, but an ethics of criticism (see Siebers, The Ethics of Criticism) or, more specifically, an ethics of critical writing. Miller would disagree. He says he is concerned with “something that at least has a chance to be concrete, namely the real situation of a man or woman reading a book, teaching a class, writing a critical essay” (The Ethics of Reading 4). But it turns out that the social reality of the classroom and the materiality of writing are not “concrete” enough. He immediately clarifies:

The metaphorical jump from the event of facing a person to the supposed event of “facing” a text is thus crucial here. But even without my point about the unlocatability of reading as an event, it is still hard to see how reading can have an “ethics” except by way of a public or at least social development of itself, which means by way either of writing or of the give and take of actual discussion. Miller agrees, in any case, that an “ethical moment” (8) must be located in reading before an ethics of reading can be imagined.

The problematics of this whole matter can be approached from another direction. Why, namely, do Hillis Miller and a few of his contemporaries, and nowadays everyone, invariably call their treatments of this or that text “readings,” and not, for example, “interpretations”? Miller suggests an answer to this question: