![]()

Part I

English in the world today

![]()

Section A

Problems and contexts

![]()

1 Introduction: defining and identifying problems

As I wrote in the general introduction, we begin by looking at the phenomenon of English in the world and considering the ways in which the language presents challenges for those who use or work with it as part of their everyday routine. The heading for this first section is ‘Problems and contexts’, and by formulating the topic in this way we immediately begin with presuppositions both about the relations people can have to the language, and the approach we are going to take towards its study. It is taken for granted in the use of this subheading that English in the world is, in certain circumstances, a problem. Indeed, the book as a whole is devoted to identifying the nature of these reputed problems, and reporting on theoretically informed practical solutions to them. Before stepping directly into this task, though, it is worth considering what constitutes a ‘problem’ in this context. Why should English present challenges for those who use or engage with it around the world? And what do these challenges consist of?

To jump straight to the punch line, the short answer is this: in the ordinary day-to-day activities of life, the use of English as a means of communication may not be – or at least not seem – in any way problematic. For an increasingly large number of people across the globe, the use of English is a normal and everyday occurrence, and one they will likely not reflect upon in any explicit way. Instead, it is something they simply do. To borrow a metaphor that has recently become popular in parts of the sociolinguistics literature (e.g. Shohamy, 2006; García, 2009), ‘English’ can be thought of not as a noun but as a verb. That is, English is an activity rather than an object; it is something people do rather than something they acquire, possess, or use.

The point here is that it is impossible to fully abstract the entity away from its actual use. And indeed, when all is going well it is not necessary to abstract it away from its use. We do not need to have a general or theoretical concept of English to be able to communicate in English. To borrow Mikhail Bakhtin’s observation about the way we instinctively and unreflectively use different speech genres whenever we speak, we can say of all our commonplace communicative habits that “[w]e use them confidently and skilfully in practice, and it is quite possible for us not even to suspect their existence in theory. Like Molière’s Monsieur Jourdain who, when speaking in prose, had no idea that was what he was doing, we speak in diverse genres without suspecting that they exist” (Bakhtin, 1986, p. 78). For the proficient English speaker, the majority of communication in English will be conducted without any need to know about such things as the typological character, the grammatical structure or the philological history of the language they are using. I was able to communicate perfectly adequately in English long before I knew the first thing about linguistics; just as I am able to watch the world going by outside my window without knowing the slightest thing about optics.

It is when the user of the language comes up against difficulties of some sort, or is presented with particular challenges, that a shift takes place: the shift from procedural knowledge to propositional knowledge. In other words, it is when a user of the language runs into a problem that strategies which draw upon an analytic understanding of language become useful. This is when it is necessary to know not simply how to do something, but how to understand what it is you are doing. By understanding what it is you are doing, it is then possible to see how you might be able to change it: to modify, improve or repair it.

The problems that produce the need for this shift of perspective can be of various types. They can relate to communication and intelligibility, to identity and cultural politics, or to professional concerns such as education. In each case, use of the language will not simply be a matter of intuitive communication but will involve issues which are causing a ruction of some sort in other social interactions. And although such problems can and do occur with respect to any language, the extensive reach and global profile of English means that it especially is the site for a great many such problems, and is thus worth dedicated investigation.

As one of the key precepts of this book is going to be that the exact nature of these language-related problems rely for their scope of meaning on the contexts in which they occur, it is important to examine real-life instances. For this, we need to begin with some representative examples of the nature of English use around the world today. It is to this, therefore, that we turn in the first chapter.

![]()

2 English in the world today

English and variety: examples

Varieties and functions

Let us begin by looking at a selection of examples of English usage from various global contexts. For each example I have provided a basic explanation of the context, followed by the data and then a commentary summarising some notable features. In the sections that follow, as we map out the areas in which applied linguistics problems relating to the global use of English most often occur, I will refer back to these examples and offer further analysis, drawing out the significance of the features on display here for World Englishes studies.

Example 2.1

The first extract is from a conversation between three people: M, S and H. M is an American and speaks English as his mother tongue; S is a German speaker; and H is a Chinese speaker. They are discussing the price for some decorating work. In this, and subsequent transcripts, each of the turns in the conversation (i.e. each instance that the conversation switches from one speaker to another) have been numbered so they can be easily referred to in the discussion that follows.

1 M: | Let’s say we need decorations and we need it cleaned up. |

| | What’s your bottom line? |

2 S: | What’s my what? |

3 M: | What is the bottom line. What, what’s the- |

4 H: | bottom line, yes |

5 M: | least you can do it for? The least it can be done for? |

6 S: | The lowest, uh- |

7 M: | |

8 S: | price? Four thousand. |

9 M: | Four thousand. |

| | (Roberts, 2005, p. 151, cited in Seidlhofer, 2009, p. 201) |

Comment

In this short extract, English is being used as a means of communication by a small group who do not share a common first language. As such, they are using it as a lingua franca. They are engaged in a task – negotiating the price of some decorating work – which involves the need for mutual understanding and agreement. By the end of the exchange they appear to have reached this common understanding, but for a short while in the middle (turns 2–7) they have trouble fully understanding each other, and the flow of communication stumbles over the meaning of the phrase “the bottom line” (turn 1). This is an idiom which the Oxford English Dictionary records as being of US origin, and is not an expression with which S and H, the non-native speakers in the dialogue, appear to be familiar. By rephrasing his question though, M eventually makes himself understood, and the interaction has a successful outcome.

Example 2.2

The next two passages are both excepts from poems. The first is by the Nigerian writer Frank Aig-Imoukhuede (1932–2007), and the second (Example 2.3) by the Indian writer Nissim Ezekiel (1924–2004).

Example 2.3

Comment

Both these poems are early examples of writers using a style of English which reflects or draws upon the ways in which the language is used in their native communities. As such both display linguistic features which are divergent from a standard British or American English, and instead represent an ‘indigenised’ use of the language. Frank Aig-Imoukhuede’s poem ‘One Wife for One Man’ (Example 2.2) is written in Nigerian Pidgin English. Among the many features which mark this as different from standard English is the spelling (which reflects the pronunciation; so ‘fader’ instead of ‘father’) and the distinct vocabulary of words such as oga meaning ‘master’ and borku meaning ‘plenty’.

Nissim Ezekiel’s ‘The Patriot’ (Example 2.3) is also imitative of local patterns of speech, in this case a form of Indian English. Again there are several features which differ from standard British or American English. These include the use of the present progressive (e.g. “I am standing for peace”) instead of the simple present tense (standard British or American English would have “I stand for peace”); the reduplication of words such as “fighting fighting”, which is used to intensify the meaning (Gargesh, 2006); and missing out the object after a transitive verb, as in the phrase “modern generation is neglecting” (where standard British or American English would normally be “the modern generation is neglecting it”). Many of these grammatical patterns are to be found in Indian languages and have been transferred onto the way English is spoken in this context. In the poem they are used specifically to indicate a local voice for the opinions that are being expressed, and when the poem was published in the anthology Contemporary Indian Poetry in English (Peeradina, 1972) it was given the title ‘A very Indian poem in Indian English’, to highlight the deliberate use of this local style of the language.

It should be noted that both these poems are representations of these types of English. That is, they are not transcriptions of real-life spoken data in the way that the speech in Example is. Instead, they are creative imitations of typical local speech patterns which are being used as part of the creative repertoire of the two poets. The Nissim Ezekiel poem, for example, uses these patterns of speech as part of the characterisation of what is a slightly comic central character, while Aig-Imoukhuede’s poem is about the clash of cultures that resulted when the “white man come”, and the use of Pidgin helps to illustrate this on a textual as well as thematic level.

Both poems also mark early attempts by writers to develop a distinctive use of English in literature which is authentic to their own experiences of the language. A critic writing in 1971, for example, commented that Aig-Imoukhuede “is one more example of an African poet who is eager to use English as his medium and yet find a voice which is at once African and genuinely his own” (Roscoe, 1971, p. 42). Likewise with Ezekiel, this attempt to represent an ‘Indian English’, although viewed in some quarters as verging on caricature (Parthasarathy, 1976, p. 8), has also been described as “break[ing] the stranglehold exercised on poetic style by the notion of a standard language … [by] allowing poetry to explore parts of the human structure it had not earlier known it could accommodate or inhabit” (Patke, 2009, p. 281).

Example 2.4

This next extract – which is again real-life data – comes from a conversation between two young women, Dream and Cherry, who are originally from Thailand but at the time of this exchange were living in London. They are conversing via an instant messenger service on their mobile phones, and the topic of the conversation is the state of Dream’s love life. Again the individual turns in the conversation are numbered, and phrases which are not in English are translated below the original utterance in square brackets.

| 1 Cherry: | oh |

| 2 Cherry: | Ken-noi ngai |

| | [How about Ken-Noi? (Ken and Noi are popular TV personalities in Thailand)] |

| 3 Dream: | Mai wai la |

| | [No way] |

| 4 Dream: | Too young |

| 5 Dream: | They are the same age as my students loei |

| 6 Cherry: | shouldnt b phd... |

| 7 Cherry: | should b undergrad... |

| 8 Cherry: | but everything too late now |

| 9 Cherry: | herr |

| | [<sigh>] |

| 10 Dream: | Why don’t u have a bf? |

| 11 Cherry: | i have |

| 12 Cherry: | hahaha |

| 13 Cherry: | but i want exciting thing banggg |

| 14 Dream: | I can’t believe. U r cute mak mak na |

| | [You are cute!] |

| 15 Dream: | Gu wa laeww |

| | [This is what I think] |

| 16 Dream: | Dee mak I will tell ur bf dee gua lol |

| | [Great. I’d better tell your boyfriend about your plan] |

| 17 Cherry: | oh |

| 18 Cherry: | no la no laaa |

| | [No] |

| 19 Cherry: | jai rai |

| | [You are mean] |

| 20 Dream: | Eeh eeeh |

| | [Ha ha ha] |

| | (Example from Seargeant and Tagg, 2011, p. 10) |

Comment

What is particularly interesting in this extract is that although both participants have Thai as their mother tongue, they regularly switch into English as well. English is not being used as a lingua franca as it is in Example 2.1, therefore, because the two women share a common language. Instead, it is part of their everyday repertoire of linguistic resources, and they are shifting between different languages (what is technically known as codeswitching) as part of the natural flow of the conversation. This switching happens extensively, both between turns (e.g. between 3 and 4), and in the middle of utterances (e.g. turn 16).

As well as the codeswitching, this extract is also notable for the way that the English they use is influenced in many places by their native language, and so again displays features which are not found in standard British or American English. For example, there is the frequent use of discourse particles (words added to an utterance – often at the end – for the purpose of emphasis) such as ‘loei’ (turn 5), ‘banggg’ (turn 13) and ‘laaa’ (turn 18). These particles are frequently used in Thai (Smyth, 2002), and when they get transferred over to English they create what could be described as a specifically ‘Thai English’. Another distinctive feature is the use of particular grammatical patterns such as “everything too late now” (turn 8) where the copular verb “is” is dropped (standard British or American English would have “everything is too late now”).

This conversation also includes several linguistic features which are often found in the informal use of language online. For example there are instances of contractions such as ‘b’ for ‘be’, ‘u’ for ‘you’ and ‘bf’ for ‘boyfriend’ in turns 6 and 10. There is also some non-standard punctuation, such as the lack of capitalisation and apostrophes in turn 6 (“shouldnt b phd”). The result is a use of English which again is far from standard, but which, in this instance, is related not to the geographical or cultural backgrounds of the people using it, but to the medium of communication they are using. It is thus known as computer-mediated discourse, and the combination of this, the codeswitching and the ‘Thai English’ illustrates the diverse and creative forms English can take in the era of globalisation.

One final point of note in this example is the way that the Thai language is rendered in the Roman alphabet. Thai has its own alphabet, but here – due to the fact that the mobile phones the two women were using did not have the correct software for them to write in this alphabet – they transliterate everything into Roman script. The need to do this (i.e. the fact that the technology they are using favours the Roman alphabet rather than the Thai) may well be a motivating factor for why they chose to switch into English so frequently – and points to the way that language choice can be related to a range of social, cultural and material factors.

The visual display of English

The last two examples are slightly different from those above. These are illustrations of the visual display of English in public spaces. For both, the context in which they are displayed and the material form they take are very important, and illustrate something about the influence of English on cultural landscapes around the world.

Examples 2.5 and 2.6

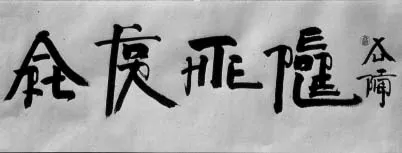

The photo in Figure 2.1 is of the hoarding for a flower shop in Kuwait. Figure 2.2 is an artwork by the American-based Chinese artist Xu Bing, from a series called ‘Introduction to Square-Word Calligraphy’.

Figure 2.1 FLY Flowers, Kuwait (Photograph courtesy of Hossein Zand, with thanks to Barbara Mayor)

Figure 2.2 Square Word Calligraphy: ‘Art for the People’ (2002), ink on paper (Xu Bing, 2004, p. 338)

Comment

As with the conversation between...