![]()

1

The Birth of English

Clues in placenames

The most important factor in the development of English has been the arrival of successive waves of settlers and invaders speaking different languages. The history of placenames in Britain is closely connected to the presence of various languages at various points in time.

English does not originate in Britain, but can be traced back to the language of the various tribes in what is today’s north-west Germany. If you had been standing in Britain 2,000 years ago, you would probably have heard a language more like modern Welsh. Today, we consider languages such as Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Irish Gaelic and Breton to be ‘Celtic’ languages. Ancient Britain was inhabited by various Celtic-speaking tribes, of which the ‘Britons’ were one. Appendix II displays the Indo-European ‘family tree’ of languages. Note the Celtic branch. The idea is that languages grouped on particular branches have features in common. Thus, the Irish word for English full is lán, and it is the same in Scottish Gaelic. Hence, the assumption here is that these languages are closely related; they form part of the Goidelic branch. Welsh is a slightly more distant Celtic relative, forming part of a Brythonic branch, and has the form llawn. Both Breton and Cornish, the other members of that branch, have the fairly similar leun. These Celtic language branches are descended from a kind of mother language higher up the family tree. No written records survive of this ‘mother Celtic’ – it is a hypothetical language, Proto-Celtic, reconstructed by linguists (an asterisk before a word indicates that the word is a reconstruction and not recorded anywhere). For example, we can infer that the Proto-Celtic word for English full includes the sounds [l] and [n], and a vowel, probably [a], in between (square brackets represent sounds; we will consider the representation of sounds in upcoming units). Most scholars give the form *φlāno as the Proto-Celtic word (the letter <φ> represents a sound somewhat like that represented by <f>, but only involving the lips in pronunciation). English full, of course, is very different, but it does, as we shall see later in this unit, have Germanic cousins with fairly similar words. Ultimately, if we go back far enough in time (and well before surviving written records) or higher up the family tree, the theory is that we arrive at a language, Proto-Indo-European, which is the common ancestor of all languages in the tree.

As far as vocabulary is concerned, the impact of the Celtic languages on English has been minimal – a mere handful of words. Scholars have claimed that words such as brock (a badger) and dun (a dark greyish brown colour) and bard (a minstrel-poet) have a Celtic heritage, and there may also be a case for truant and gull. The predominant Celtic word-legacy is in placenames, such as those below:

Cities: Belfast, Cardiff, Dublin, Glasgow, London, York

Rivers: Avon, Clyde, Dee, Don, Forth, Severn, Thames

Regions: Argyll, Cumbria, Devon, Dyfed, Glamorgan, Kent, Lothian

We cannot be totally sure what these placenames might have originally meant. Like many other placenames, they pre-date written records, which are preserved in significant quantities in English only from about AD 700. Indeed, the study of the history of placenames in general is characterised by careful reconstruction (and a bit of guesswork!). Apart from records, we can, for example, compare placenames with words in surviving Celtic languages or consider the geography of the places in question. Thus, we can make a reasonable guess about the meaning of the placename element ‘pen’ in the placename Pendle, because ‘pen’ in today’s Welsh means a summit or top, and there is indeed a hill top at Pendle. Such detective work in tracing the history of words, whether placenames or any other type of word, is a matter of ETYMOLOGY. Etymology will be an important issue in both Units 5 and 6. The study of both placenames and personal names in particular is referred to by linguists as ONOMASTICS.

- 1.1 Consider the list of placenames above. What areas of the British Isles seem to be well represented? Can you guess why this might be?

The first notable group of invaders to join the Celtic-speaking tribes of Britain were the Romans, bringing Latin (check Latin on the family tree in Appendix II). Although Julius Caesar had raided Britain in 54 and 55 BC, it was not until AD 43, under Emperor Claudius, that the real occupation of Britain got under way. Lowland Britain (the midlands and south), which already had had some cultural and trading contact with continental Europe and Rome in particular, was taken over relatively swiftly, but today’s Wales and northern England – the highland areas – took a generation, and the invasion ground to a halt at Carlisle, where Hadrian’s Wall was ostensibly built to keep out tribes (e.g. the Picts) further to the north (i.e. in what we would think of as Scotland today). In the north of England, not only was the terrain more difficult but there was a lack of people to do business with, and so a ‘military zone’ was set up. In the low-lands to the south, there was a more highly developed system of aristocratic leaders, attracted by Roman culture and willing to do business. The result was deep societal divisions in the British Isles. The survival of Celtic placenames in some areas (see Exercise 1.1) must partly reflect the lack of domination and/or assimilation of Romans in those areas.

The Romans often Latinised existing Celtic placenames, rather than inventing completely new names. London is a Celtic placename, supposedly based on the personal name Londinos, meaning ‘the bold one’. It was made more like Latin by being changed to Londinium. Few place-names surviving today are straightforwardly based on single Latin words. If invading powers want a swift administrative transition, they do not change all the placenames, otherwise confusion will result. One example of complete change is Catterick, which apparently is derived from Latin cataracta ‘a waterfall’ (and there is a waterfall at Catterick). A less dramatic change is to add a placename element, of which the most notable from Latin are:

castra = a camp, walled town (e.g. Lancaster)

portus = port (e.g. Portsmouth)

via strata = paved way, a ‘street’ in a town (e.g. Stratford)

In the above illustrative examples, only the first, Lancaster, has a Celtic element. ‘Lan’ is from the River Lune, and Lune is probably from Old Irish ‘slán’, meaning ‘health-giving’ (which wouldn’t be my description of the river today!). The non-Latin and non-Celtic elements mouth and ford of the other examples, Portsmouth and Stratford, have a Germanic background.

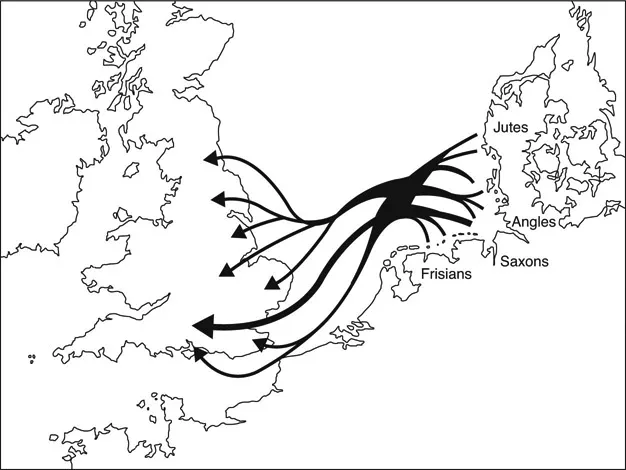

The English language has its roots in the language of the second wave of newcomers – in the Germanic dialects of the tribes of north-western Europe (including areas of today’s north-west Germany). Check English and its location in the family tree in Appendix II. As we already noted, a number of modern Germanic languages clearly have words that are related to English full. For example, Modern German has voll, Dutch vol, Swedish full and Danish fuld. These tribes, conventionally referred to as the Anglo-Saxons, entered Britain in the year AD 449, after the Romans had with-drawn in AD 410. At least that is what the standard histories say, drawing their inspiration from Bede, a monk at Jarrow in Northumberland, who completed his ecclesiastical history of the English people, the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, in 735 (the surviving early eleventh-century manuscript can be seen at: http://image.ox.ac.uk/show?collection= corpus&manuscript=ms279b, and a translation can be found at: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/bede/history.html). According to Bede, three tribes – Angle, Saxon and Jutish – were initially invited in by the British king Vortigern, to help fight off the Picts to the north. Eventually, they became discontented with the deal offered by the Britons, so they helped themselves to British territory. Bede follows this with an apocalyptic account of mass murders, buildings being razed to the ground and refugees. Map 1.1 shows where these tribes are thought to have come from (there is particular uncertainty about the location of the Jutes).

Map 1.1 Angle, Saxon and Jute invasions

Bede’s account, however, is unreliable. Note he was writing roughly 300 years after the event. Moreover, histories are selective interpretations, written by writers with their own agendas. Bede’s claims about specific tribes invading in a purposeful and warrior-like manner would help create a heroic Anglo-Saxon history behind which the various tribes and kingdoms of Briton could unite. Placename evidence seems to suggest that there were identifiable tribes. The Angles appear to have settled in and given their name to what is now East Anglia (comprising Norfolk = ‘north folk’ and Suffolk = ‘south folk’), and also spread to Mercia (the Midlands) and further north to Northumbria (‘north (of the) Humber’, and south-east Scotland). The Saxons appear to have remained in the south, as evidenced by the area names Sussex (‘south saxons’), Essex (‘east saxons’), Middlesex (‘middle saxons’) and the old name for the south-west Wessex (‘west saxons’) (Wessex extended from Sussex to Devon and as far north as Gloucestershire; its most famous capital was Winchester). The Jutes seem to have remained largely in Kent and the Isle of Wight. However, it is possible that the terms ‘Angle’, ‘Saxon’ and ‘Jute’ were overlapping or even synonymous, not least of all because commentators nearer that time were inconsistent in their usage. Archaeological evidence does not support the idea of invading hordes, mass destruction and the Britons fleeing to the north and west. Many excavations suggest slow dilapidation of Romano-British buildings, and not sudden destruction. There was indeed some warfare and displacement of Britons, but there is also evidence that many Britons, particularly in the east, adopted the new prestigious Germanic culture, and there is evidence of intermarriage. Moreover, the Anglo-Saxons never got as far as the northern and western extremes of Britain. The Celtic languages – notably Cornish, Welsh, Irish Gaelic and Scottish Gaelic – proceeded relatively independently of English in what are today Cornwall, Wales, Ireland and Scotland. Each established its own literary tradition, and, excepting Cornish, which died out in the eighteenth century, are living languages today.

This, you might think, closes the Celtic chapter in the history of English. But not so. More recently, scholars have pointed out that it is very likely that the Celts outnumbered the Anglo-Saxons, and that the bulk of the Celts, especially in south-eastern areas, switched to speaking the Germanic dialects that constituted English. So, given that there were...