(ING) is perhaps the most studied variable in the English language (if not in all linguistics), because it is variable in all varieties of English and is sensitive to most of the factors sociolinguists have considered: phonology, morphology, syntax, dialect, style, class, ethnicity and sex. Moreover, the general picture is essentially the same across dialects for most factors, so that even in places as far apart as Los Angeles, Norwich, and Australia, men tend to have a higher rate of the alveolar variant [ɪn] than women. This regularity and stability is attractive for analyzing language use in the fraternity, where members are not all from the same dialect area.

Fischer’s classic (1958) study of (ING) and Trudgill’s (1972) study both focused on male behavior. Fischer’s differentiation between the ‘model’ and ‘typical’ boy shows that differences among men may be due to a speaker’s orientation to authority. Similarly, Trudgill claimed that the ‘covert prestige’ he found among men in Norwich reflected their identification with the ‘roughness and toughness supposedly characteristic of [working class] life which are . . . considered to be desirable masculine attributes’ (1972: 182).

Coding

Each token of (ING) was coded as alveolar and preceded by an untensed vowel (N), or velar (G). Each token was also coded for the independent variables of speaker, activity type, following phonological environment, and grammatical category. Speakers were coded individually.

Activity type is similar to the style factor in Labov (1966) and other studies. Most variation studies are based on interviews, and therefore do not have the possibility of coding for activity type. Activity type is defined both emically and etically [from within the group and as the observing analyst sees it]; members themselves recognize a difference between ‘hanging out’ and meetings, the two main types on which I have focused. ‘Meetings’ simply involve tokens of (ING) spoken during the full weekly meetings. A random sample of meetings was coded. Socializing takes place at a number of locations and with differing numbers of participants; however, dividing this activity type would not yield comparable results, because each speaker was not recorded in all socializing contexts. Tokens for the socializing activity type were exhaustive for each speaker, because this activity type was the most difficult to tape, and therefore fewer tokens were available. I also coded interview tokens. All interviews were not identical in setting; not all were private, and I did not have a close relationship with all interviewees. Interviews were coded for the first 45 minutes, or the complete interview, if shorter. Because of the volume of talk in interviews, they comprise over half of the total tokens. Some word lists and reading passages were recorded with some speakers.

Internal factors coded included following phonological environment and grammatical category. In addition to grammatical categories outlined by Houston (1985), the marker fuckin’ was included as a separate category. This word functions as several different grammatical categories, but is almost categorically pronounced as N.

Results

Tokens were analyzed using the IVARB variable rule multiple regression analysis program for DOS [a form of variable rules analysis, or VARBRUL]. All factor groups were selected as significant at the .05 level in the step-up-step-down procedure. Table D1.1 lists the results for all factors from a single run, including probabilities and percentage of N.

The non-discrete differences of probabilities in the grammatical status factor group roughly match Houston’s (1985) findings for grammatical category, although I have not analyzed the results in detail, since this issue has no bearing on my research question (except to account for any interaction between factors). For the same reason, I will not speculate on the striking differences between my results and Houston’s for the following phonological environment. The only similarities between the results are the effect of a following velar consonant (favors G), and [-back] consonants, which slightly favor N.

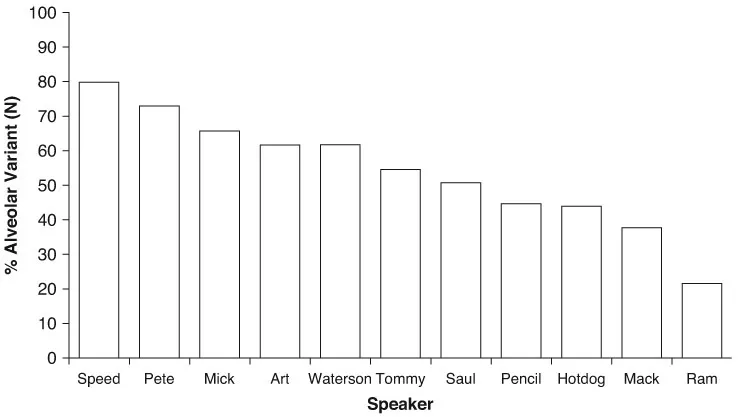

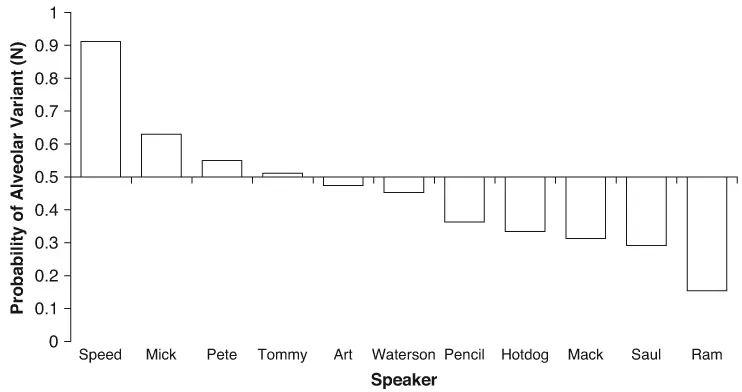

The results for the speaker factor group are reproduced graphically in Figures D1.1 and D1.2.

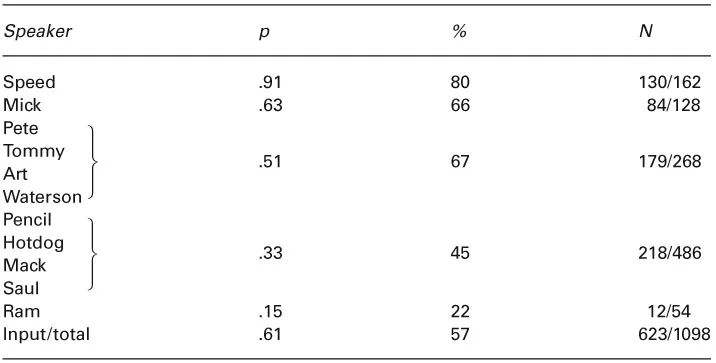

In Figure D1.1, the percentages of N use are shown, yielding a range from 80 percent for Speed to 22 percent for Ram. Note the gradual slope; there are no clear groupings among speakers. This situation changes for the variable rule results in Figure D1.2. Although the distribution still appears smooth, notice that Pete is not highly likely to use N (compared with his percentage of 73%), while Saul is very unlikely to use N (compared with his percentage of 51%). The disparities between percentages and probabilities suggest that there is an interacting factor that gives these men higher percentages than would be expected from their probability scores. The probabilities also suggest a way of grouping the speakers: two speakers favor N, but to differing degrees (Speed and Mick), another group disfavors N (Pencil, Hotdog, Saul, Mack, and possibly Ram), while the other speakers form a middle group (Pete, Art, Waterson, and Tommy) who neither strongly favor nor disfavor N. These groupings were for the most part ratified through further Varbrul analysis, which returned nonsignificant (p>.05) differences among Pete, Tommy, Art, and Waterson in one group, and Pencil, Hotdog, Mack, and Saul in another. However, Speed and Mick were significantly different from each other (p<.05), and Mick could not be combined with the middle group. Similarly Ram could not be placed with the group including Pencil. Table D1.2 shows the combined grouping. There is no common social factor uniting these groups; all show differences in the length of time they have been members of the fraternity, geographical origin and class. Ethnicity does not explain any differences, since all the men are white except Saul, whose family is Afghani. There could be a combined age and region effect, with Pencil, Hotdog, Mack, and Ram all being older members from the Washington, D.C. area (but Saul is from Rochester, New York), while Tommy, Art, and Waterson are younger members from the Washington, D.C. area (but Pete is from Virginia Beach, Virginia). These possibilities cannot, however, be investigated without a larger sample of speakers from regions other than Northern Virginia.

Table D1.1 Varbrul probabilities and percentages of alveolar (N) application of (ING) for all factor groups

| Speaker | p | % | N |

|

| Speed | .91 | 80 | 130/162 |

| Mick | .63 | 66 | 84/128 |

| Pete | .55 | 73 | 100/137 |

| Tommy | .51 | 55 | 16/29 |

| Art | .47 | 62 | 40/65 |

| Waterson | .45 | 62 | 23/37 |

| Pencil | .36 | 45 | 50/111 |

| Hotdog | .33 | 44 | 77/175 |

| Mack | .31 | 38 | 32/84 |

| Saul | .29 | 51 | 59/116 |

| Ram | .15 | 22 | 12/54 |

| Input/total | .62 | 57 | 623/1098 |

|

| Activity type | p | % | N |

|

| Socializing | .72 | 75 | 180/240 |

| Interview | .54 | 53 | 294/550 |

| Meeting | .30 | 47 | 124/264 |

| Reading | .10 | 54 | 25/46 |

| Input/total | .62 | 57 | 623/1098 |

|

| Following environment | p | % | N |

|

| [-back] cons. | .57 | 63 | 291/465 |

| Vowel | .51 | 58 | 226/391 |

| Pause | .36 | 41 | 75/184 |

| [+back] cons. | .35 | 53 | 31/58 |

| Input/totaI | .62 | 57 | 623/1098 |

|

| Grammatical status | p | % | N |

|

| ‘Fuckin’ | .97 | 97 | 86/89 |

| Progressive | .60 | 69 | 356/513 |

| Preposition | .55 | 60 | 9/15 |

| Participle | .48 | 54 | 47/87 |

| Noun | .42 | 49 | 49/99 |

| Participial modifier | .26 | 36 | 15/42 |

| Gerund | .16 | 24 | 59/242 |

| Adjective | .11 | 18 | 2/11 |

| Input/total | .62 | 57 | 623/1098 |

Figure D1.1 Percentage of alveolar variant for speakers

Figure D1.2 Variable rule probabilities of alveolar variant for speakers

Table D1.2 Probabilities and percentages of alveolar (N) application of (ING), for the combined speaker factor group

However, speaker was not the only external variable that affected the use of (ING); activity type was also significant (Table D1.1). Socializing highly favored N at 75 percent (.72 probability), while meetings disfavored N strongly at 47 percent (.30 probability). Interviews fell in between at 53 percent (.54 probability).

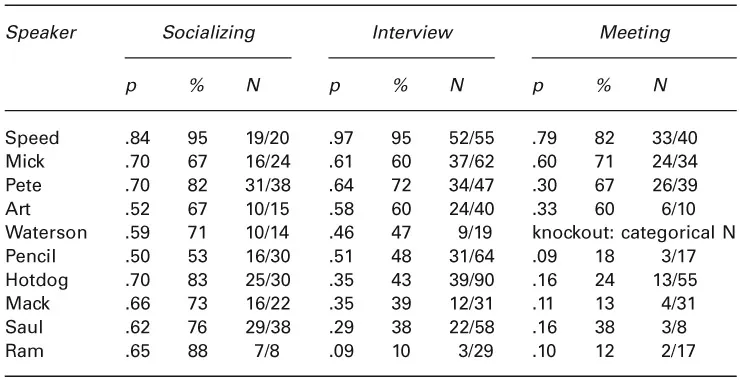

The variable rule analysis does not tell the whole story, however. As Labov (1972c: 240) eloquently noted, the interaction between style (activity type) and class (speaker) is one of the interesting aspects of this variable. Thus it is important to investigate the interaction patterns through a cross tabulation. [. . .] Across activity types, the pattern of speaker stratification changes dramatically; most speakers move in the same general direction, but they do not move in lock-step. Moreover, the differences between speakers increase from socializing to meeting. In the socializing activity type, most of the speakers congregate in a 67–88% range (21 percent difference). This clustering is found again in the interview results, with a group congregating in a 36–60% range (24 percent difference). In the meeting activity type, however, there is no such ‘core’ middle group; the speakers are spread out almost evenly. [. . .] Speed continues his outlier status in all three activity types.

I also performed a Varbrul analysis in which the speaker and activity type factor groups were combined into one group. A single factor thus consisted of a speaker and an activity type (e.g., Saul in meeting activity type). This factor group was selected as significant in a step-up-step-down procedure (p<.05). The probability weightings are shown in Table D1.3. [. . .] The speakers [here] are ordered as they were in Table D1.1, with Speed, the most likely to use N overall, at the top.

The probabilities in this chart show an even more striking interaction. Note that almost all speakers favor N in the socializing activity type, in a range of .50 to .84, and no speakers disfavor N. In further Varbrul analysis, all speakers except Speed were able to be combined into one group in the socializing activity type. In the interview activity type, speakers exhibit the largest range of weightings. This is probably due to the fact that the interviews varied in style, so that some speakers considered them more like socializing, and others more like meetings. Speed and Ram were the high (.97) and low (.09) outliers, respectively, while the rest of the men split into two groups, one disfavoring N (.32), another slightly favoring N (.56).

Table D1.3 Probabilities and percentages of alveolar (N) application of (ING) for speaker/activity type combined factor group

The meeting also shows a split in speaker groups, as confirmed through further Varbrul analysis: a large group who strongly disfavor N, in a range of .09 to .16, and two speakers who strongly favor N in meetings: Speed (.79) and Mick (.60). Note that Waterson’s weighting is effectively 1.0; his meeting tokens were excluded from the Varbrul analysis because they were categorically N. Moreover, Pete and Art (.21 combined) do not disfavor N to the same degree as the biggest group (.11). These figures show a clear differentiation among speakers within the meeting activity type, a fact that is more significant when we consider that the meeting is a relatively public activity type, while the interview is not, so that the men have access to models in the meetings, but not in the interview. The Varbrul analysis confirms the view that the men tend to use N more alike in the socializing activity type than in the meeting activity type. By investigating the differences in how the men talk in meetings, then, we should be able to understand more about the ‘meaning’ of this variable.

The speaker factor group also interacts with the language internal factor group of grammatical category [. . .]. [We can] see the strong effect of the discourse marker fuckin’: almost all speakers use N ca...