![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Thinking about Islam and politics in global perspective

There is little doubt today as to the importance of Muslim politics in contemporary world affairs. From the emergence of transnational networks pursuing global militant agendas in the name of Islam, to the persistence and transformation of traditional Islamic political parties—several of which experienced dramatic political success in the wake of the Arab Uprisings that began in 2010—to the appearance of global media personalities claiming to speak as authoritative and authentic Islamic voices: Islam and politics seem today to be everywhere. But how well do we actually understand this phenomenon? Muslim politics are certainly much discussed today, but— arguably—little or poorly understood within most circles of debate and deliberation. How can we best make sense of this highly complex, diverse, and sometimes even contradictory world of religion and politics? How to understand the relative importance of the multiple manifestations of Muslim politics around the world and the many competing voices claiming to speak on behalf of Islam? What is the difference between those Islamist movements that emphasize jihad and those that pursue politics through nonviolent, even democratic, means—and how do they relate to each other? What possible futures might we predict for political Islam?

These are a few of the questions that this book addresses. In some cases possible answers to several of these puzzles will be offered, while in other instances the book aims to provide the reader with the background information and analytical tools necessary to reach his or her own conclusions. It should be clarified that this book, while certainly ambitious in scope, does not attempt to provide anything like a grand, unified theory of Islam and politics. While key cross-cutting themes are certainly identified, the primary emphasis throughout is on the inherent pluralism and diversity of Muslim politics— that is, on the impossibility of a single theory to account for political Islam. It is suggested, however, that there are better and worse explanations as to why Islamic social and political movements appear and assume the forms that they do under certain circumstances. As numerous analysts of political Islam have observed over the years, particular formulations of Islam and politics certainly do seem to suit specific social, political, and economic conditions. This text is offered, then, in the spirit of a comparative, synthetic overview: a guide to the wide-ranging global landscape of Islam and politics, an introduction to the broad ecology of thought and practice in contemporary Muslim politics, and a critical survey of some of the key ideas advanced by leading scholars in their efforts to explain the phenomenon of political Islam. In a modest way, this book also hopes to offer the rough contours of its own distinctive analytic— one that emphasizes the importance of the interplay between global and local contexts of Muslim politics in a time of unprecedented social interconnectedness and interdependence.

The structure of the book is roughly as follows. This introductory chapter orients the reader to some of the key themes and concepts surrounding the discussion of religion and politics more generally (e.g. the idea of religion and politics as separate domains; debates on secularism) and the specific challenges we face when dealing with this topic in the context of Islam. Readers are also asked to reconsider some of their assumptions about just what counts as politics, and how to recognize the presence of politics or religion in a given setting and social relationship. In other words, even though we may often be dealing with Muslim-majority countries, how do we know when Islam is actually a relevant factor in a given political situation—that is, how can we tell when Islam really has an influence? Because this book seeks to emphasize the wider global context of Islam, this first chapter also offers some suggestions about how to approach the interplay between local and global levels of analysis in a world of intense interconnectedness. While not a text on globalization per se, it is nevertheless important to evaluate whether and how some of the trends and transformations commonly associated with this term may inflect our analysis of Muslim politics in distinctive new ways.

The analysis offered in this book is firmly rooted in a belief that an understanding of the interplay between Muslim societies and various local, regional, and world political issues throughout history is absolutely crucial to achieving any kind of handle on contemporary Muslim politics. To this end, the next two chapters briefly explore key themes and concepts in the history of Islam and politics, while progressively introducing a new framework for understanding today’s political Islam. Chapter 2 covers a broad swath of history from approximately the seventh century CE up to the late eighteenth century. It looks at Muslim politics in the time of the Prophet Muhammad and immediately after, explaining the emergence and consolidation of certain key institutions and norms in Muslim politics prior to the expansion and fragmentation of the early Muslim community. The various regional polities and Islamic empires that rose and fell over the subsequent ten centuries are briefly surveyed before acclimatizing the reader to the onset and implications of European colonialism in the Muslim world. The chapter then analyzes a variety of Islamic responses to Western imperialism before moving on to examine the process of modern state formation in the Muslim world in the post-colonial period. The chapter concludes with an overview of the interaction between world politics more broadly and Muslim politics in and across particular local and national settings. We look at how what seemed initially to be a crisis for Islam in the face of widespread support for the secular nation-state model in the early twentieth century quickly evolved into the precursors of what eventually became the political project of Islamism.

Chapter 3 provides a detailed overview of the emergence of modern Islamism through an examination of post-colonial state formation in the Muslim world. It looks at major Islamic political theorists in the twentieth century, and also the key activists and thinkers who gave birth to the Islamist project. The conventional model of state-based Islamism is then illustrated through a detailed study of the formation and evolution of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) in Egypt—the prototypical modern Islamist movement, and the model for many subsequent groups around the Muslim world. We analyze the ideology and organization of the Brotherhood, and trace its development through three generations. The chapter concludes by surveying major developments in twentieth-century Islamism in a number of other key settings. An extensive textbox in this chapter provides an overview of key theories and debates in the study of political Islam so as to familiarize the reader with the major explanatory paradigms currently available for understanding Muslim politics.

Having identified the major animating forces behind Islam and politics today, the next section of the book seeks to provide the reader with a wealth of concrete empirical detail regarding how these trends are actually playing out in specific Muslim contexts. The next four chapters offer detailed case studies of Islam and politics across a range of national, regional, and trans-national settings. The reader will find chapters that deal with topics such as Islamist participation in elections and normal political processes, the nature and evolution of Islamism in those countries that style themselves as “Islamic states,” and the impact of conflict and war on Muslim politics. Key countries—such as Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia—are covered, but in an attempt to emphasize the global context of Muslim politics, this section moves away from the conventional country-by-country case study model to include dedicated sections on important transregional and transnational movements such as Al-Qaeda and the global jihadist movement.

The final chapter presents an argument that Muslim politics—through the intervening effects of globalization, and the emergence within certain Muslim communities of a political consciousness transcending national borders as well as conventional spaces of formal politics—is entering a phase in which the methods, goals, and vocabularies of Islamism are undergoing considerable transformation. It is suggested that “classic” Islamism, as a totalizing project seeking to capture state power, increasingly is forced to compete with Muslim political agendas above and below the state that seek, respectively, to establish transnational Islamic polities, or to open up spaces for the inclusion of religion in public life and greater recognition of Muslim identity claims within the context of broadly secular societies. The idea that the net effect of these developments is moving us towards a condition that some analysts have termed “post-Islamism” is considered through a discussion of several contemporary Islamic movements that operate outside the formal political realm, but whose activities nonetheless need to be seen as forms of Muslim politics. The book concludes with some reflections on how these disparate strategies and politics will likely play out in the coming years.

Islam in the World: Some Basic Facts

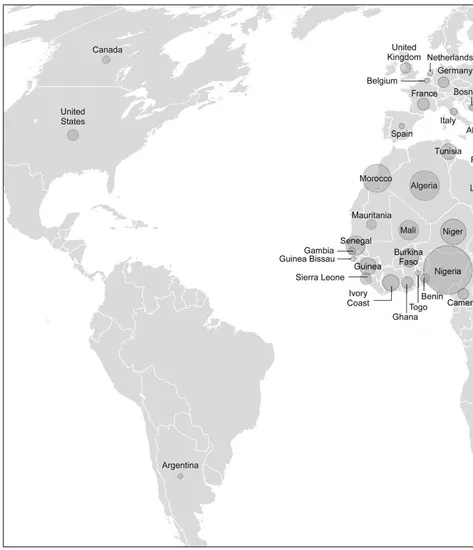

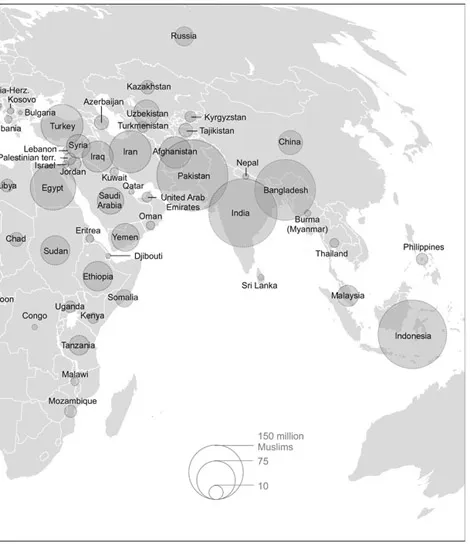

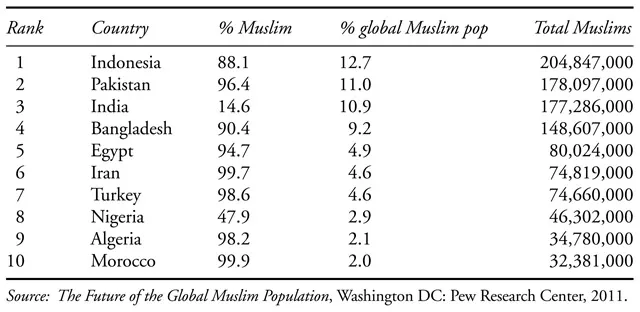

Before getting into substantive discussion, it will be helpful to orient the reader to the subject matter at hand: Muslims and the Muslim world. Comprising approximately 1.6 billion people across almost every continent, Islam constitutes one of the great world religions today—and certainly the fastest-growing.1 Often thought of as a Middle Eastern phenomenon, it is worthwhile taking note of the fact that the four countries with the greatest number of Muslims are actually in Southeast Asia (Indonesia) and South Asia (Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India). The states of the former Soviet Union are home to large numbers of Muslims, and significant populations are to be found in West and East Africa. So it is important immediately to disabuse ourselves of the idea that the Middle East and the Muslim world— despite their common overlap in contemporary discourse—are coterminous. Today we also hear much about the idea of Islam and the West as two separate entities. As Chapter 2 demonstrates, it makes much more sense in historical perspective to emphasize overlap and exchange between these world cultures, rather than conflict and incompatibility. Furthermore, with sizeable Muslim populations in Western Europe and North America, Islam is an increasingly important religion today in many of the countries that we would think of as part of the West.

It almost goes without saying that, given this size and geographical breadth, Islam is a thoroughly diverse phenomenon—a fact that makes it difficult and even dangerous to try conclusively to define what Islam has to say about a given idea or situation, or what the “Islamic” view on something might be. Inevitably, this perspective will vary significantly from context to context. As explained in greater detail below, this book uses the term “Islam” to refer to a particular tradition of discourse and practice that is variously defined across multiple social and historical settings. There is therefore no connotation of normativity implied in our usage, for example, of the term “Islamic.” Islam should always be considered in relation to how it is understood and experienced in specific contexts and circumstances. That does not mean that anything and everything counts as Islam. Embodied within the very idea of a tradition is the notion that this tradition has boundaries—but these, it should be emphasized, are always open to contestation and negotiation. Likewise, there is no attempt made here to define who or what counts as Muslim. For our purposes a Muslim is anyone who identifies him or herself, at least in part, with Islam—regardless of how the latter may be understood.

Broadening Our Understanding of Politics

It may strike the reader as slightly strange to begin with a discussion of the definition of politics, but this is necessary given the wide range of phenomena under consideration in this book, some of which we propose to treat as “political” although they would not generally be considered part of the commonplace world of politics. Conventional understandings of politics tend to equate it with particular sets of activities and institutions—more specifically, the processes through which actors pursue governmental power in the context of the modern nation-state. We generally have a sense of the kinds of activity that count as political (e.g. elections, coups d’état, lobbying) and the relevant sorts of actors and institutions (political parties, nation-states, militaries). To be sure, many of the Muslim countries and organizations covered in this volume correspond quite closely to this model. In Jordan and Kuwait, for example, Islamist political parties contest parliamentary elections in the hope of having a greater role in legislative processes. In the case of certain other social forces examined here, however, we need to recalibrate some of our assumptions in order to recognize them as properly political. For example, a few of the movements we look at reject the very model of the nation-state, and seek instead to establish forms of political community premised on very different norms and principles. It is still not difficult, however, to see such groups as political, since it is clear that they are seeking to challenge prevailing institutions through which social power is exercised. More challenging, however, are the cases of certain mystical orders or movements that emphasize personal piety—many of which ostensibly eschew politics altogether. The approach advanced by this book is one

Map 1.1 The global Muslim population

that would see any rejection of politics as a particular sort of political act. Usually what is being articulated in such claims is a challenge to a specific vision of public morality that understands social order and “the good” to accrue from the direct exercise of power via the institutional channels of government. By way of an alternative, these movements seek to emphasize an understanding of the public good as something that best emerges through an emphasis on personal piety and devotion—that is, the idea that one creates the good Islamic society not by top-down legislation, but rather through the collectivization of individually pious Muslims.

Table 1.1 Largest Muslim populations by country

With this illustration in mind, we can say that, for our present purposes, it is important to regard as political all actors and activities involved in the establishment, maintenance or contestation of particular visions of public morality (“the good”) and of social order. There is, of course, something to be said for the analytic utility of narrow definitions. Indeed, if we widen our understanding of politics too far, then everything becomes political— hence, for purposes of analysis, nothing is political. Well aware of this pitfall, it should be pointed out that, in the vast majority of cases examined in this book, the end point of Muslim politics involves challenges to state authority via methods and tactics easily recognizable as political according to standard criteria. A broader definition of politics is being proposed primarily to enable us to recognize, and include in our analyses of these processes, social actors and even ideas whose political relevance might not otherwise be immediately discernible. It is an approach that permits a richer, more nuanced, and more comprehensive appreciation of the relationship between Islam and politics.

Religion and Politics in Europe and the Muslim World

Before we wade into the comparative analysis of Muslim politics that constitutes the central focus of this book, it would be worthwhile to dwell briefly on a number of more general issues surrounding the analysis of religion and politics in a globalizing world. The intersection of religion and politics is notoriously tricky terrain to navigate, and we would do well to examine some of the baggage we inevitably bring to the analytical table. This is not only because religion and politics are usually highly emotive and polarizing subjects unto themselves, touching on issues around which people frequently stake strong senses of identity, morality, and worldview. This is also because we often tend to hold particular views about the proper relationship between these two spheres, and feel varying levels of comfort when we encounter situations in which the two seem to be mixing. Different societies around the world inevitably have different histories, traditions, and norms relating not only to the intermingling of religion and politics, but to the very definition of the boundaries that delineate and—sometimes— separate these two domains. Of particular importance here, of course, is the vexed question of secularism. Secular norms are arguably part of the...