![]()

Understanding clinical evidence

Chapter 1

The importance of clinical evidence

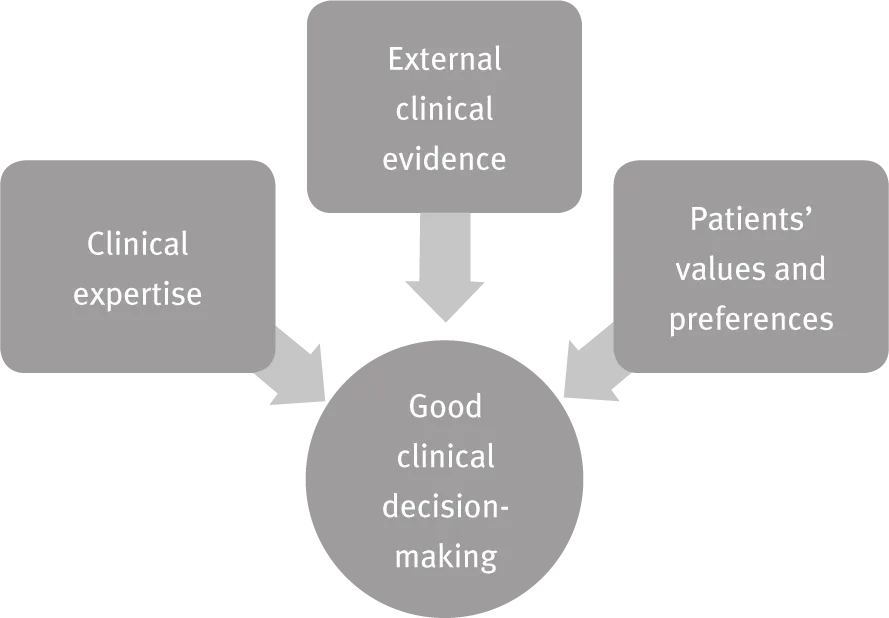

Combining the skill that an individual clinician has gained through experience and practice with the best available external clinical evidence is called evidence-based practice (EBP). It is also known as evidence-based medicine (EBM) and evidence-based healthcare (EBHC).

Definition

Clinical evidence is the information from research studies that helps decide the value of screening programmes, diagnostic tests, management plans and treatments.

Evidence-based practice

Integrating evidence-based medicine with patients’ own values and preferences is the basis of good clinical decision-making.

Expert opinion or evidence-based practice?

In the past, clinicians relied on their own experience and the opinions of experts to make clinical management decisions. While these judgements were often correct, the careful application of research evidence has been found to improve patient care, making it safer and more effective.

Grounding care in clinical evidence has now become routine. Concepts like P values, meta-analysis and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are such an important part of decision-making that clinicians need to understand them.

The types of clinical evidence

Researchers design a study to answer a specific clinical question, for instance “Is a steroid injection likely to be more effective than physiotherapy for tennis elbow?”.

Early in their planning, researchers need to check whether their question has been answered already. If it has, there is no point in wasting resources on replicating the work of previous researchers.

A study is therefore designed to answer either a new question, one that hasn’t been adequately answered before, or to confirm an answer that is unexpected or is particularly important.

The research method used depends on the question. The different methods are described in more detail in the following chapters, but here is a summary list of common ones.

Randomized controlled trials (Chapter 8) are a type of prospective study, i.e. one whose patients are identified and then followed up into the future. In these studies the risk of bias (see Chapter 5) is minimized by randomly allocating the subjects to one of two or more treatments; it could be used to compare the effectiveness of a new treatment for temporal lobe epilepsy with the existing best treatment, for example. The P value (Chapter 7) gives information on how likely it is that any difference in outcome was due to chance.

Cohort studies (Chapter 9) are another type of prospective research. Here, researchers follow groups of patients who are alike in many ways but differ in one or more particular characteristics. They may follow them for some years to look at outcomes, i.e. what happens to them. For example, researchers may study a group of patients to compare the effect of high and low levels of computer use on long-term visual acuity. A statistic called a risk ratio is used to compare the outcomes of these two ‘cohorts’ of patients.

A case–control study (Chapter 10) is an example of a retrospective design, i.e. one that looks back over time: the outcome of interest has already happened and the researchers want to know what factors may have influenced it. These studies compare a group of patients having a condition, the ‘cases’, with a group without it, known as the ‘controls’. This method could be used to assess whether hospital patients who have developed a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during their stay are more (or less) likely to have taken aspirin in the last month than similar, ‘matched’ patients without a DVT. The odds ratio is a statistic that compares these groups.

Research on diagnostic tests (Chapter 11) typically compares a test with a ‘gold standard’ test, for example how a new blood test for coeliac disease performs compared with the results of small bowel biopsies in the same patients. The resulting specificity and sensitivity values show how often the test is negative in patients without the condition, and positive in those with the condition, respectively.

Qualitative research (Chapter 12) finds out about what people are thinking and why. It could be used to find out why patients do (or don’t) see their GPs if they have a productive cough. Researchers find the key themes and can develop a hypothesis that fits them together.

Health economic evidence (Chapter 15) typically examines the costs and benefits of different healthcare interventions, treatments or policies. When applying economic tools to the world of healthcare, researchers may try to answer broad questions on health policy. They may also look at a more specific question; for instance, one that asks which treatment is most cost-effective for control of hypertension, when compared to an alternative. Our financial resources are limited, so health economists work out how to optimize the provision of healthcare.

Can one paper do it all?

Very occasionally a single research paper causes a big change in practice. However, more often individual pieces of research don’t give the whole answer, but are small building blocks to it.

One way for a clinician to plan an evidence-based approach to a clinical problem is to appraise and synthesize all the relevant papers. This is very time-consuming, so many rely on the work of others that have done that for them.

A systematic review (Chapter 13) is a literature review that identifies, assesses and synthesizes all the relevant research evidence. An author might review all the papers on the non-surgical management of appendicitis, for instance.

A meta-analysis (Chapter 13) combines the numerical data from different studies. Pooling the results of different studies on survival after cardiac stents, for example, might give a more reliable idea of the size of the effect than any of the individual underlying studies.

Clinical guidelines (Chapter 14) are recommendations that authors have made as a result of their own systematic review. An example is a guideline on the management of type 2 diabetes by diet alone.

The five ‘A’s

The key steps in using clinical evidence are as follows.

- Ask : define the clinical question, for instance, whether or not a specific treatment is better than placebo for a particular condition.

- Acquire evidence: make a systematic retrieval of the available literature and data.

- Appraise : critically appraise that evidence to assess its validity (how close it is to the truth) and clinical applicability (how useful it is likely to be for our own patients).

- Apply the results: make changes in clinical practice as a result of our appraisal of the evidence.

- Assess the outcome: evaluate the effect that those changes have on patient care.

![]()

Chapter 2

Asking the right questions

Before we can make any progress with finding the most appropriate clinical evidence and then working out if this evidence is valid and useful to us, we need to frame the question that we want to answer. In day-to-day clinical life we have lots of clinical questions to answer, so it also helps to know how to prioritize them.

See Chapter 18 for a tool that will help us to design our own clinical questions.

Definition

Clinical questions can be divided into two categories:

- foreground questions – these are about decisions that need to b...