eBook - ePub

AFA9 Spy vs Spy

Australia Foreign Affairs 9

Jonathan Pearlman

This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

AFA9 Spy vs Spy

Australia Foreign Affairs 9

Jonathan Pearlman

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The ninth issue of Australian Foreign Affairs explores the rapidly evolving espionage threat facing Australia as changes in technology enable malign actors to target individuals, officials, businesses and infrastructure. Spy vs Spy examines how Australian agencies can defend against this attempt to not only steal secrets but also disrupt the workings of government and society. Contents of this issue include: An essay by Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong

"The Fix": a high-profile strategist reflects on how to solve Australia's foreign affairs challenges

"The Back Page": award-winning journalist Richard Cooke dissects key foreign policy terms

Correspondence on AFA8: Can We Trust America?

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is AFA9 Spy vs Spy an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access AFA9 Spy vs Spy by Jonathan Pearlman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Géopolitique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

GéopolitiqueDRAWING THE LINE

Witness K and the ethics of spying

Kim McGrath

In the first week of January 2019, a private jet landed at Presidente Nicolau Lobato International Airport in Dili, the capital of Timor-Leste. Former Victorian premier Steve Bracks emerged into the monsoonal heat and was greeted by staff from the office of Xanana Gusmão, Timor-Leste’s chief maritime boundary negotiator. They drove Bracks to the waterfront café at the Novo Turismo Resort and Spa, where Gusmão was waiting. The subject of the meeting was Bernard Collaery, Gusmão’s former lawyer, who was pleading not guilty to breaches of Australia’s intelligence act.

Collaery’s charges related to an Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) operation in Dili in 2004, in which Canberra is believed to have recorded Timor-Leste officials’ private discussions about maritime boundary negotiations with Australia. In 2013, the Australian government revealed the allegations of spying. Five years later, in June 2018, Attorney-General Christian Porter consented to charges being laid against Collaery and a retired ASIS agent known only as Witness K for “conspiring to reveal classified information”.

Gusmão led the Timorese resistance against the Indonesian occupation in the mountains of East Timor and, after his capture in 1992, from his jail cell in Jakarta. In 2002, he became Timor-Leste’s first president, and later served as its prime minister.

Bracks says Gusmão wanted to know what he could do to support Collaery, who had been his lawyer following Timor’s independence from Indonesia in 1999 and on several subsequent occasions.

Gusmão saw it as a moral issue. He said he would travel to Canberra if necessary, to give evidence in support of Collaery and Witness K, because, he told me, it would be against his conscience not to. He saw them as “honourable men” who should have been lauded for their actions. From his viewpoint, they had revealed a crime. A crime against one of the poorest countries in the world, by one of the richest.

In April 2020, the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory was due to hold a preliminary hearing about the extent to which Collaery’s case would be heard in public. Gusmão was planning to go to Canberra to give evidence, until COVID-19 travel restrictions led to the hearing date being vacated. Witness K’s plea date was also postponed. Collaery’s hearing was re-listed for May. The hearing was held in secret, so it is unknown if Gusmão’s evidence was tendered or if he appeared by video link.

The prosecution of Collaery and Witness K throws a spotlight on the nexus between politics and intelligence, and the unfettered power of ministers in Australia’s intelligence regime. Unfortunately for Collaery and Witness K, and the 7000 staff currently working in Australia’s ten intelligence agencies, it also shows that opportunities for an operative to challenge a direction to perform an immoral or illegal act are limited and likely to be career-ending.

“People in ASIS are not devoid of conscience … but there is no avenue for them to raise concerns.”

According to section 11 of the Intelligence Services Act 2001, ASIS and the other five agencies to which the Act applies are to work “only in the interests of Australia’s national security, Australia’s foreign relations or Australia’s national economic well-being”. Australians accept the need for extreme secrecy around spying operations aimed at combatting terrorism and other security threats. But does that social licence extend to using espionage for illegal, immoral or corrupt acts? Should the state use its spies against a friendly government for purely economic gain, either for the state or for private companies?

Leading security analyst Desmond Ball warned that “the relationship between intelligence and policy is complex and delicate. It can easily become politicized, so demeaning the intelligence process and ultimately risking national security.” This is what happened in Canberra in 2004–05. And it is arguably what drove Witness K to later raise with the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS) disquiet within ASIS about the operation.

The office of the IGIS is responsible for ensuring Australia’s intelligence agencies act “legally and with propriety, comply with ministerial guidelines and directives and respect human rights”. In early 2008, Witness K approached the IGIS, Ian Carnell, alleging that a cultural change within ASIS had led to his constructive dismissal. According to a statement Collaery made to federal parliament, part of the complaint involved an operation Witness K “had been ordered to execute in Dili, Timor-Leste”. Carnell allowed Witness K to take private legal action, but this could only be done through a lawyer with the security clearance to act for intelligence agents. Collaery was on a list of such lawyers. Despite his well-known connections with the Timorese leadership and the fact that Witness K’s grievance involved the Dili operation, Collaery was appointed Witness K’s lawyer.

Collaery is restricted by national security legislation from talking about the operation. Clinton Fernandes, an Australian Intelligence Corps officer from 1997 to 2006 now at the University of New South Wales, is not so constrained. In his 2018 book Island off the Coast of Asia, Fernandes writes that the listening devices installed in the Palácio do Governo

were turned on and off by a covert agent inside the building. They then beamed the recording by microwave signal to a line-of-sight covert listening base set up inside the Central Maritime Hotel … The digital recordings were then allegedly couriered across town to the Australian embassy, and sent to Canberra for analysis.

The 127-room Central Maritime Hotel was a converted Russian hospital ship that was rebuilt in Finland, used as a hotel in Myanmar and then towed to Dili because there were no hotels or restaurants of suitable standard for international visitors. It was conveniently moored opposite the waterfront white-stuccoed Palácio do Governo.

The 2005 Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor estimated that more than 150,000 people, a quarter of the population, were murdered or deliberately starved to death between 1974 and 1999, when the territory was under Indonesian rule – a brutal occupation aided and abetted by Australia. In 2004, when the Dili bugging occurred, the Timorese remained physically and emotionally traumatised. Of the 177 countries on the United Nations Development Programme Human Development Index measuring poverty, Timor-Leste languished at 158, one place above Rwanda.

Retired diplomat Bruce Haigh says ASIS officers involved in the Dili operation were put in an impossible position: “People in ASIS are not devoid of conscience. I’ve known many ASIS and ASIO officers over the years … They want to keep Australia, and Australians, safe. They would object to such an immoral operation, but there is no avenue for them to raise concerns.” Former ASIS spy Warren Reed argues that most intelligence officers have “a keen sense” of democratic values and “will generally stand firm against attempts by their service’s management to diverge from those widely accepted norms of behaviour”.

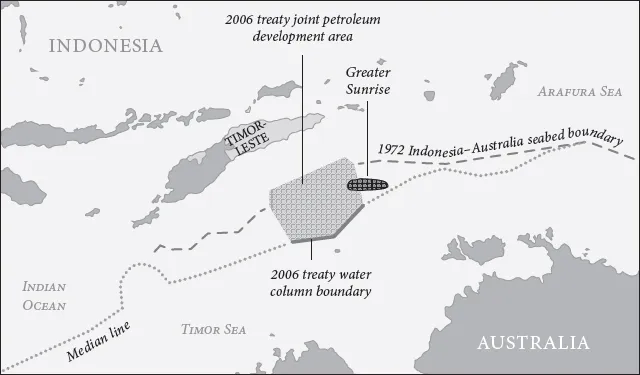

The Greater Sunrise oil and gas fields, which lie in the Timor Sea between Australia and Timor-Leste, were the cause of a long and controversial dispute between the two neighbours.

The current director-general of ASIS, Paul Symon, has stressed that ASIS acts only in response to a list of priorities set out by the National Security Committee (NSC), chaired by the prime minister. ASIS reports to the minister for foreign affairs, also a member of the NSC, who must authorise specific activities. In 2004, that minister was Alexander Downer.

When the operation became public in 2013, Downer, long retired from politics, defended Australia’s tactics in the Timor Sea negotiations. He told the ABC’s Four Corners program in March 2014 that he could not confirm or deny the spying. But he added: “The Australian government was on Australia’s side in the negotiations and we did our best to make sure that we were able to achieve our objective.”

De Mello reported Downer told him “Australia could bring meltdown to East Timor if it so chose”.

Australia’s objective was to retain rights to hydrocarbon-rich areas of the Timor Sea much closer to Timor than to Australia. In the early 1960s, Australia issued petroleum exploration permits in the Timor Sea to Woodside, now Australia’s largest natural gas producer, in areas contested by Indonesia and Portuguese Timor. Australia refused Portugal’s requests for talks and instead negotiated a treaty with Indonesia in 1972. The agreed boundary skirted the edges of the permits issued to Woodside and other companies – well north of the median line.

Woodside discovered the Greater Sunrise oil and gas fields in 1974. The following year, with Australia’s covert support, Indonesia invaded Portuguese Timor. Unlike Portugal, which had argued for a median-line boundary, Indonesia suggested joining the end points of the 1972 treaty, which would have put Greater Sunrise entirely in Australian waters. Despite UN resolutions calling on Indonesia to withdraw, Australia commenced negotiations with Indonesia in 1979 to agree on a boundary between Australia and occupied East Timor. This amounted to Australia formally recognising Indonesia’s sovereignty in Timor, the only Western nation to do so.

However, once negotiations commenced, Indonesia argued for a median line. It took a decade to reach agreement on the Timor Gap Treaty, infamously signed by foreign ministers Gareth Evans and Ali Alatas in a jet as they drank champagne over the Timor Sea in December 1989. The treaty established a “resource-sharing arrangement” (not a permanent boundary) that gave Australia rights to the lucrative oil and gas fields off the coast of East Timor.

By the late 1990s, the possibility of an independent East Timor was threatening the treaty. If East Timor became independent, the deal Australia had negotiated with the illegal occupier would cease to exist. East Timor would have rights under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, ratified by Australia in 1994, including the right to a 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The Timor Sea is approximately 350 nautical miles wide, so Australia and East Timor would have overlapping EEZ entitlements. The boundary would be determined by international law, and would likely involve drawing an equidistant line halfway between the coasts of neighbouring states.

Downer worked hard to keep the Timor Gap Treaty alive, even before East Timor gained independence. A month after Indonesia’s surprise January 1999 agreement to a vote of self-determination in East Timor, Downer visited Jakarta and sought out Xanana Gusmão, who was under house arrest after six years in Indonesia’s top-security prison, Cipinang.

Downer talked to Gusmão about, among other things, the smooth transition of the Timor Gap Treaty from Indonesia to East Timor. In an interview with filmmaker Gil Scrine in Dili in March 2019, Gusmão said he was surprised that the Australian foreign minister wanted to talk about the treaty. He recalled telling Downer that he was not “prepared to talk about oil and gas” and instead pleaded for international troops to quell the escalating violence.

In October 2000, Sérgio Vieira de Mello, head of the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET), met with Downer and other ministers in Canberra and was also surprised that their “key preoccupation” was the treaty. Amid the deployment of more than 5500 Australian personnel in East Timor, and the massive development challenge facing the Timorese people, Canberra’s focus was on the energy resources in the Timor Sea. De Mello cabled a colleague after the meetings that the Timor Sea issue “elicited a strong – even strident – reaction from Downer and his department”. De Mello reported Downer told him “Australia could bring meltdown to East Timor if it so chose”.

Between July 2001 and April 2003, Downer made four trips to Dili. Initially his aim was to ask UNTAET to step into Indonesia’s shoes and accept the terms of the Timor Gap Treaty. This was a big request, as Australia’s claim beyond the median line was as belligerent and out of step with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea as China’s nine-dash line in the South China Sea. Australia’s diplomacy also risked alienating a friendly, desperately poor neighbour that was the subject of a massive international effort to establish statehood.

UNTAET’s negotiators pushed back, arguing for a boundary reflecting international law – a median line and lateral boundaries that would put all of Greater Sunrise in Timorese waters. But the UN negotiating team was under-resourced and overworked – and, for all we know, Australia’s intelligence agencies may have also been secretly lending assistance to Australia’s negotiators.

Two months before Timor-Leste’s independence, and just weeks after an American company, Oceanic Exploration, offered to fund a Timorese application to the International Court of Justice to determine the maritime boundary, Australia withdrew from the jurisdiction of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and the maritime division of the ICJ. In a media release on 25 March 2002, Downer stated, “Australia’s strong view is that any maritime boundary dispute is best settled by negotiation rather than litigation.”

UNTAET had some small victories, but when the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste came into existence on 20 May 2002, its first official act was to sign the heads of agreement for the 2002 Timor Sea Treaty with Australia. Modelled on the Timor Gap Treaty, this created a revenue-sharing arrangement, not a maritime boundary, and left 80 per cent of Greater Sunrise outside the “Joint Petroleum Development Area”. It was a huge win for Australia.

Timor-Leste asked for a 50–50 share of Greater Sunrise. Australia refused

In November 2003, 100 international non-government organisations signed a letter to John Howard, criticising Australia’s “callous” approach and warning that its long-term interests were “best served by a stable and prosperous East Timor”. The Howard government had a different assessment of Australia’s interests. It considered the possibility of Timor-Leste gaining sovereignty to the median line in the Timor Sea such a threat “to Australia’s national security, foreign relations or economic well-being” that it was apparently necessary to direct ASIS (and possibly other intelligence agencies) to support Australia’s negotiating team. This was a damning indictment of Australia’s negotiators, some of the best and brightest lawyers in government, backed by the resources of multiple departments. Timor-Leste’s team was led by former US ambassador Peter Galbraith, supported by a handful of idealistic young lawyers.

One of the issues that reportedly drove Witness K to complain to the IGIS was his concern that intelligence assets were being diverted from the war on terror to the Dili operation. The Timor Sea negotiations started in 2004, just three years after al-Qaeda terrorists ploughed passenger jets into the twin towers in New York on 11 September 2001. Following the attack, Howard invoked the ANZUS Treaty and committed Australia to support “United States–led action against those responsible for these tragic attacks”. This resulted in Australia’s participation in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, heightening the security threat in Australia and increasing pressure on its intelligence assets.

A year after September 11, Downer told parliament that the government had received information “about a generic threat to Australian and United Nations interests in South-East Asia”. At the time, more than 20,000 Australian tourists visited the Indonesian island of Bali each month. Three days after Downer’s statement, DFAT amended its travel advice for Indonesia but, in bold type, stated that services were “operating normally” in Bali.

This was a catastrophic failure of Australian intelligence. On 12 October 2002, two members of Jemaah Islamiyah, a South-East Asian extremist Islamist group with links to al-Qaeda, set off bombs in the Sari nightclub and Paddy’s Bar at Kuta Beach in Bali, killing 202 people, including 88 Australians and 38 Indonesians. Days later, the Howard government was forced to admit that two weeks before the blasts, it had received a US intelligence report that included Bali among targets for an impending terrorist attack. Howard told parliament that the report was analysed by Australian intelligence assessors, who decided that travel warnings did not need to be upgraded. Applying the narrowest definition of “intelligence”, Howard insisted he had been assured there was no specific information warning of an attack on 12 October in Bali. The IGIS came to the same self-serving conclusion. Warren Reed said it was “an unthinkable and unforgivable failure of the intelligence network”.

In July 2004, the Howard government released a white paper on terrorism. In the foreword, Downer wrote that the government was responding to the threat with a “sustained and strategic campaign”. ASIO and ASIS budgets had been boosted, the paper noted, because intelligence offered “the best chance of detecting terrorist activity and allowing us to take steps to prevent an attack”. Jemaah Islamiyah was named as a key threat.

Two months later, Jemaah Islamiyah claimed responsibility when a car bomb exploded in the driveway of the Australian embassy in Jakarta. In addition to the suicide bomber, eight people were killed, including the embassy gardener and four Indonesian police, and more than 150 wounded.

A m...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Editor’s Note

- Andrew Davies: Mission Impossible

- Danielle Cave: Data Driven

- Kim McGrath: Drawing the Line

- Anne-Marie Brady: Party Faithful

- Penny Wong: The End of Orthodoxy

- The Fix

- Reviews

- Correspondence

- The Back Page by Richard Cooke

- Back Cover

Citation styles for AFA9 Spy vs Spy

APA 6 Citation

Pearlman, J. (2020). AFA9 Spy vs Spy ([edition unavailable]). Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1324245/afa9-spy-vs-spy-australia-foreign-affairs-9-pdf (Original work published 2020)

Chicago Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. (2020) 2020. AFA9 Spy vs Spy. [Edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. https://www.perlego.com/book/1324245/afa9-spy-vs-spy-australia-foreign-affairs-9-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Pearlman, J. (2020) AFA9 Spy vs Spy. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1324245/afa9-spy-vs-spy-australia-foreign-affairs-9-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. AFA9 Spy vs Spy. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd, 2020. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.