Chapter One

Policing History

A Military Handbook on the Southern Provinces

“How can I trust you?” A. smiled, but he was staring intently at me. I was caught completely off guard. My housemate had suggested I talk to A., a member of her family: “I think it would be better you ask him, he knows a lot about the situation here!” I could not offer much in response to A.’s question. “Erm … here’s my card?” He nodded. “Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies,” it said under my name. He smiled. “Okay, you can take notes.” For A., the conflict in southern Thailand was a conflict about history. The Thai state, he explained, was trying to extinguish the history of the once glorious and independent sultanate of Patani that used to be the center of Islamic scholarship in the region. This history is no longer taught at state schools, said A. Only local pondoks keep it alive, yet these traditional Islamic boarding schools have also now come under state control. A. elaborated that what he called the “movement” was therefore determined to fight for the right of Patani people to learn and teach their own history again.1

A.’s suspicion reveals how sensitive discussions about Patani’s history have become in the context of the southern conflict, and how signifiers of religion—the word “Muslim” on my card—function to indicate support for a certain version of history. According to A., history not only defined the essence of Patani but also determined the cause of the insurgency movement, with which he seemed to identify. His highlighting of Patani’s past glory reminded me of the strategies that insurgents reputedly use in recruitment, relaying a similar narrative to convince prospective members that they have to “fight to regain control [of their] history.”2

The contentions about Patani history have been so fierce that the 2006 report of the National Reconciliation Commission warned, “Violence in the southern border provinces may be regarded as a problem of history.” This problem of history is not simply a clash of two nationalisms, but rather characteristic of the Thai imperial formation.3 As much postcolonial scholarship teaches, the production of history is one of the central discourses through which modern imperial power produces hierarchical difference. Dipesh Chakrabarty has demonstrated that the modern discourse of history—what he calls “historicism”—conditions the project of imperial modernity. The idea of human progress through secular time legitimated the notion of civilizational development. In its spatialized version, history distanced the West from the non-West, placing the latter into the “waiting room of history.”4 This discourse, as Fernando Coronil argues, establishes relations based on disassociations, thereby “separating relational histories, reifying cultural difference, and turning difference into hierarchy.”5 History in the imperial formation thus manages difference by stabilizing its own linear, dominant form of time, and distancing those temporal Others that threaten to disrupt its narrative of homogenizing progress.6

In fact, Siam’s own imperial entanglement shaped the state-led enforcement of a new practice of historiography at the end of the nineteenth century. The royal elite championed the modern discourse of history to demonstrate Siam’s civilized status compared with Western nations.7 It was thus precisely during the transition of the old Siamese empire to the modern imperial formation that modern historical discourse gained ground. In the course of a relatively short period of time, the elite coined two neologisms that delineated this new field of knowledge: borankhadi (literally, “antiquity studies,” and later used to designate “archaeology”) and its replacement prawattisat (literally, “past-science”).8 Significantly, the official endorsement of the modern discourse of history helped to produce a number of disassociations that still centrally structure the narrative of Thailand’s civilizational development today. Most important for our purposes here, modern Thai historiography has elided Siam’s own imperial encroachment on former principalities and tributary states such as Patani, and has produced a gendered and racialized narrative of a historical Buddhist kingdom wherein a Thai lineage is protected from external (colonial) threats by its paternal royal rulers.9

A speech made by King Chulalongkorn (Rama V, r. 1868–1910), who is still revered in Thailand as the great modernizer, to inaugurate the Antiquarian Society in 1907 illustrates the modern narrative of Thai history.10 In it, the king differentiated the new practice of historiography from the old tradition of writing royal chronicles, and he urged his listeners to collect documentary evidence from proper historical sources instead of following the stories of rulers told in the chronicles. He deployed racialized terms to argue that the written documents available, though few, distinguished the Thai nation from other “negro nations” that only relay their history “by word of mouth.” A considerable part of the speech was devoted to a long list of cities and former city-states that he identified as “old settlement(s) of the Thai race” based on archaeological remains of Buddhist temples. These (city-)states were “now joined together as united Siam.” Using this evidence, members of the society should help to “compile a history of Siam over the past 1000 years.”11

The new historiography that Chulalongkorn wanted to establish could narrate the secular progress of modern Siam without relying on old sacred chronicles, and would strive to be as white as the written documents available allowed. The king’s speech thereby reveals that the imperial concept of civilization was already ingrained in elite thinking at the time. In colonial scholarship, only peoples with written historical records were seen as capable of civilizing historical progress and as worthy of investigation within the newly established discipline of history, whereas oral historical traditions were left to the discipline of ethnography.12

This colonial idea of history became a political program in Chulalongkorn’s lecture; he described history as a “discipline” that acted both as an objective norm for ruling the kingdom (“to evaluate ideas and actions as right or wrong, good or bad”) and as a means for governing his subjects (“to inculcate love of one’s nation and land”).13 Just as he presented Siam as an imperial formation that anachronistically incorporated different city-states into its racialized realm, he imagined an imperial history that absorbed all local histories into one unified, civilized narrative of continuous progress. This history strengthened the power of the state and governed potentially unruly subjects by integrating them into its linear narrative.

Significantly, Chulalongkorn failed to mention Patani in his speech. One reason may be that in 1907, negotiations about Patani between British and Siamese authorities were still underway, and they were only settled with the Anglo-Siamese Treaty signed in 1909. The omission might also reveal the marginality of the history of the Islamic sultanate to the central narrative of modern Siam as a Buddhist kingdom. Perhaps most importantly, it effectively concealed Siam’s own imperial conquest of Patani, thus producing national memory based on the erasure of useless historical traces.14

Producing Knowledge about Southern Thailand

A similar method of streamlining history has been deployed by state authorities in the course of the ongoing southern conflict. For example, scholars interested in the history of the southern provinces will find that most of the relevant documents have been rendered inaccessible in the Bangkok National Archives—sometimes whole pages have been removed from the Archives’ catalogues. When I visited in 2019, the friendly staff advised me to hurry up and copy the few sources still available because more boxes would likely soon be removed.15

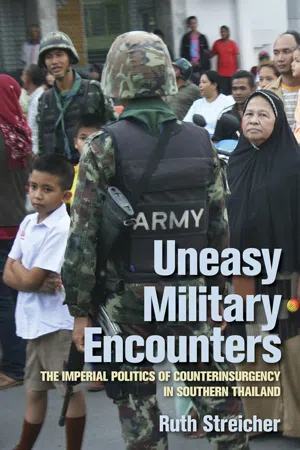

While sources on Patani history continue to disappear from the National Archives, counterinsurgents have strategically produced certain kinds of historical knowledge to police the southern population. A prime example is a handbook for military officers that the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) published as part of its initiative to win over the hearts and minds of people living in southern Thailand, titled Handbook of Operational Knowledge for Officers Working in the Southern Border Provinces.16 It was published in 2010, with two thousand copies of the first edition, and contains four thematic chapters: “Ethnic History,” “Islamic Religion,” “Lifestyles and Culture,” and “Social Circumstances.” It is larger and heavier than similar handbooks, with just over two hundred A5 glossy pages, and it is printed in color. Pictures feature prominently; approximately one third of the book consists of photographs of southern historical sites, cultural practices, and people, some of them interacting with military personnel. Harmony prevails in these photographic representations of Patani past and present, except in the illustrations to a section titled “From the Malay Resistance Movement to Muslim Separatism,” which show a group of Muslim men in prayer caps looking skeptically into the camera and, on the next page, police inspecting a motorbike destroyed by a bomb explosion.

The preface by then army commander Gen. Anupong Paochinda leaves no doubt that the ISOC produced the handbook as an integral part of counterinsurgency operations. Recognizing that the southern unrest also has “historical, cultural, religious and ethnic dimensions,” he warns that the “perpetrators of violence” use distorted information to win the “hearts and minds” of the local population and to blackmail state authorities, in the end turning people into a “mass” of supporters for the insurgency movement. The handbook consequently is designed, Gen. Anupong explains, to support military efforts to “make people in the area stand on our side” by providing military and civilian state authorities with “accurate knowledge about southern Thailand.”17

The structure of each chapter reflects how the ISOC envisioned this project of policing knowledge. The first part elaborates the topic. The second part explains the “errors” that circulate in the area, especially among the insurgency movement. The chapters end by instructing officers on what kind of facts they can cite to build understanding and convince the local population of the correct knowledge. The handbook, in other words, not only intends to educate civilian and military authorities about southern Thailand but it also tells these authorities how to use facts to educate the local population.

The epistemological grounds on which the handbook rests are central to the whole military project of building understanding. By referring to a positivistic notion of facts, the handbook aligns the military with objective truth while at the same time eliding the location of these truths. This “view from nowhere” establishes a position of dominance, and “understanding” thereby becomes a unidirectional and paternalistic undertaking of teaching the local population that proceeds from the ISOC’s purported objectivity.18 The military aligning itself with objectivity is especially noteworthy in a conflict region where claims to knowledge—about history, in particular—are among the stated reasons for violence, and in a country where the government restricts open discussions about Patani’s history. In this context, the military construction of objective truth furthers the linear narrative of Thailand’s progressive imperial formation while marking alternative histories as false.

Counterinsurgency and Knowledge Production

Manuals are a common form of knowledge production in counterinsurgency both in Thailand and internationally. The US Army’s 2006 Counterinsurgency Field Manual, for example, promotes the gathering of “cultural knowledge” as “essential to waging a successful counterinsurgency,” and uses anthropological literature to devise different methods for obtaining such knowledge. This cultural turn of counterinsurgency had wide-ranging institutional consequences. Most notoriously, US armed forces in Iraq established the Human Terrain System program, which involved embedding social scientists to conduct sociocultural analysis for military purposes.19

The shift in US military policy also had an impact on counterinsurgency strategy in Thailand. After September 11, 2001, the Thai state renewed its historically close military ties with the United States, as evidenced by its dispatching troops to Iraq and participating in, on average, forty joint US-Thai military exercises per year.20 Thai military personnel regularly receive scholarships to study at US military institutions. As the Royal Thai Embassy in Washington states, “Since 1950, well over 20,000 Thais,” including King Vajiralongkorn (Rama X, r. since 2016), have obtained such training, thus “greatly enhancing US access to all levels of Thailand’s military hierarchy.”21 Training institutions include the US Army War College and the Naval Postgraduate School, which specializes in studies of unconventional warfare. Many of the theses and reports written by Thai scholarship recipients after the flare-up of the southern conflict in 2004 explicitly deal with questions of counterinsurgency strategy and often directly refer to US examples. One of my military contacts had studied at the Naval Postgraduate School and indicated that the 2006 US manual on counterinsurgency constituted one of the central reference points for developing a counterinsurgency strategy for southern Thailand.22

In fact, knowledge production has been at the heart of counterinsurgency ever since the inception of this imperial form of policing and throughout its reincarnations during the Cold War.23 Thus Montgomery McFate, an important advocate of the integration of cultural knowledge into US counterinsurgency policy, endorsed anthropology as a discipline that had helped to “consolidate imperial power.”24 Thailand itself is a case in point, demonstrating how the gathering of cultural knowledge has been central to military policing projects, particularly with the establishment of the modern military. One of the earliest Siamese ethnographies, published in 1889, for instance, was written by the then commander of the Siamese army responsible for an area in the northeastern part of the kingdom. The article “On Different Forest Races” assembles the commander’s observations on people who live “far away from cities” in the “jungle,” and the topics included are typical of nineteenth-century anthropology: “villages and housing” as well as “marriage” and “religion, beliefs, seasonal events, and festivals.” Although it is unknown how the k...