Global demographic, economic, and environmental macrotrends describe key factors that drive global environmental politics.1 Humanity’s potential stress on the environment is to some extent a function of three key factors: population, resource consumption, and waste production. One way to measure this impact is through an ecological footprint, which measures humanity’s demands on the biosphere by comparing humanity’s consumption against the earth’s regenerative capacity, or biocapacity.2 The ecological footprint measures the sum of all cropland, grazing land, forest, and fishing grounds required to produce the food, fiber, and timber we need and to absorb the wastes emitted. Since the 1970s, humanity’s annual demand on the natural world has exceeded what the earth can renew in a year. This ecological overshoot was at a 50 percent deficit in 2010.3 This means that it now takes natural systems about 1.5 years to regenerate the renewable resources that we use and absorb the waste we produce in a year, and it could reach three years by 2050 in a business-as-usual scenario.4

Population Growth and Resource Consumption

Population growth affects the environment by increasing the demand for resources (including energy, water, food, and wood), the production of waste, and the emission of pollution. These relationships are not fixed, however, and most of the negative impacts result from how we carry out certain activities. Nevertheless, given the dominant economic and social patterns that have existed since the Industrial Revolution, the rapid growth of human population over the last one hundred years has significantly influenced the environment and will continue to do so throughout this century.

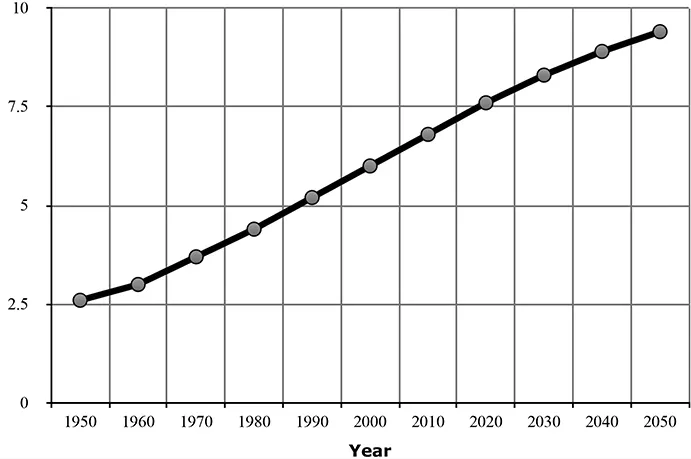

In 1900, global population stood at approximately 1.6 billion. Today it is more than 7.3 billion. It took fifty years for global population to go from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 2.5 billion in 1950. It then took only thirty-seven years for it to double, reaching 5 billion in 1987. It passed the 6-billion mark only twelve years later, reached 7 billion in late 2011, and is on pace to reach 8.5 billion by 2030, 9.7 billion by 2050, and 11.2 billion by 21005 (see Figure 1.1).

Projections of future population growth depend on fertility trends, which can be affected by economic development, education, widespread disease, and certain population-related policies. The world’s human population is currently growing at a rate of 1.18 percent annually.6 Although significantly less than the peak growth rate of 2.04 percent from 1965 to 1970, this still means a net addition of eighty-three million people per year.7 Most of this growth, as much as 92 percent,8 will occur in Africa and Asia. China and India alone already account for 37 percent of the world’s population. Moreover, the population in the forty-eight least-developed countries is projected to grow dramatically, from 954 million in 2015 to 1.9 billion in 2050 and 3.2 billion in 2100.9 Population increases have been accompanied by large increases in the consumption of natural resources, including fresh water, forests, topsoil, fish stocks, and fossil fuels. In addition, per capita consumption of natural resources has been rising much faster than population growth. For example, private consumption expenditures (the amount households spend on goods and services) increased more than fourfold from 1960 to 2000, even though the global population only doubled during this period.10 This increase is positive in that it reflects growth in the standard of living for billions of people. At the same time, the aggregate human consumption of natural resources has largely passed sustainable rates.11

FIGURE 1.1 World Population Growth 1950–2050 (Projected)

Source: “World Population,” United States Census Bureau, www.census.gov/population/international/data/worldpop/table_population.php.

As more developing countries pursue the lifestyles of North America, Japan, and Europe, the future will likely bring higher per capita rates of consumption unless resources are both consumed more efficiently and recycled more effectively. For example, the population of middle-income countries (including many of the world’s emerging economies, such as Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, and South Africa) has more than doubled since 1961, while the ecological footprint per person has increased by 65 percent.12 The United Nations (UN) estimates that the global middle class will grow from 2 billion today to 4.9 billion by 2030, with consequently large increases in demands for energy, food, water, and material goods.13

Despite large increases in the consumer class in a number of developing countries, the gulf in consumption levels within and among countries continues to draw attention. High-income countries, such as the United States, have an ecological footprint per capita that is roughly four times that of middle-income countries and five times that of low-income countries.14 The 12 percent of the world’s population that lives in North America and Western Europe accounts for nearly 60 percent of private consumption spending, whereas the 33 percent of the population that lives in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa accounts for only about 3.2 percent.15 The

United States has had more private cars than licensed drivers since the 1970s, and the average size of new, single-family houses in the United States has grown by more than 60 percent since 197316 despite a decrease in the average number of people per household.17 If everyone consumed resources at the level Americans do, it would take the planet 3.9 years to regenerate the renewable resources used and absorb the wastes produced.18

At the other end of the spectrum, nearly 1.2 billion people—one out of five—live on less than $1.25 a day, and 2.5 billion people live without basic sanitation, the overwhelming majority of whom live in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.19 A 2014 study estimated that 1.8 billion people drink water contaminated by human or animal waste and even more drink water delivered through systems that lack adequate protections against sanitary hazards.20

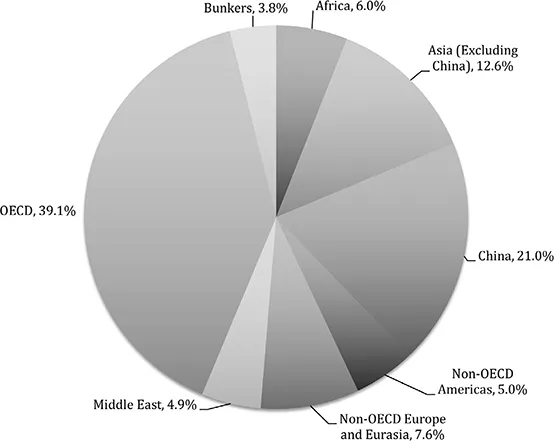

Today, the world’s richest countries use on average eleven times more energy than the poorest ones; the richest comprise only 18 percent of the world’s population but use nearly 40 percent of the world’s energy (see Figure 1.2). The United States, with less than 5 percent of the global population, uses about 25 percent of the world’s fossil-fuel resources—coal, oil, and natural gas.21 Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for about 13 percent of global population but only 4 percent of global energy demand.22 The average American consumes 3.5 times more energy than the average global citizen, 3.3 times more than the average Chinese, and 11 times more than the average Indian (and the vast majority of this energy still comes from burning fossil fuels).23 Approximately 590 million people in sub-Saharan Africa and 300 million people in India live almost entirely without access to electricity.24

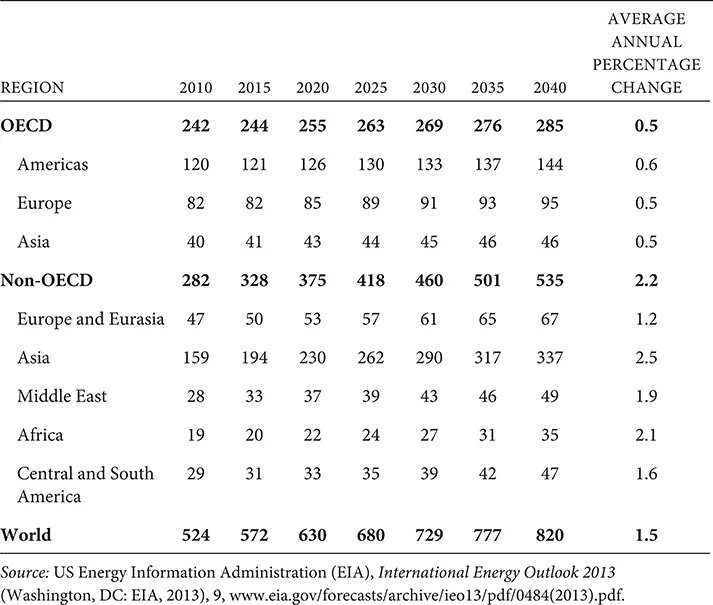

However, energy consumption in developing countries is increasing, driven by industrial expansion, infrastructure improvement, population growth, urbanization, and rising incomes (see Table 1.1). In 1980, China and India together accounted for less than 8 percent of the world’s total energy consumption; by 2014 their combined share had grown to 28 percent.25 In contrast, the US share of total world energy consumption contracted from 22 percent in 2005 to 16 percent in 2014, largely due to improved energy efficiency.26

FIGURE 1.2 Global Energy Use, 2013

Note: The term bunkers refers to international aviation and international marine fuel depots, which are not included in a specific country’s energy use statistics (or greenhouse gas emissions statistics).

Source: International Energy Agency, Key World Energy Statistics 2015 (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2015), 30, www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/KeyWorld_Statistics_2015.pdf.

Natural Resources and Pollution

Perhaps the largest aggregate impact that humans have on the biosphere is their carbon footprint (see Box 1.1), which has grown more than tenfold since 1960. The United States and China have the largest total national carbon footprints, with China emitting 27 percent of global carbon emissions, followed by the United States with 14 percent.27 In 2013, the United States emitted about twice as much carbon dioxide (CO2) as the entire continent of Africa.28 China has a much smaller per capita footprint than the United States (6.2 tons per person in 2010 versus 17.6 tons in the United States,29 although China’s footprint has increased since then), but its population is more than four times as large. India accounts for about 9 percent of global CO2 emissions, and its national carbon footprint is the third largest, but its per capita footprint is only about 1.6 tons per person.30

TABLE 1.1 Projected World Energy Consumption (Quadrillion BTU) by Country Grouping, 2010–2040

However, an energy sector transition is underway in many parts of the world, leading to an increase in the use of renewable energy. In 2014, renewables became the second largest source of electricity, behind coal. Energy efficiency improvements also helped to restrain the growth of energy demand in 2014 to just one-third of the level it otherwise would have been. According to International Energy Agency projections, energy demand is expected to grow at 1 percent per year to 2040, about half the average annual rate since 1990, due to increased energy efficiency in end uses and structural changes to the economy. CO2 emissions from power generation are expected to grow at only one-fifth of the rate at which power output will increase between now and 2040, breaking the long-standing one-forone relationship.31

Despite positive progress, efforts are not yet enough to move the world onto a pathway consistent with the 2°C climate goal (see Chapter 3). The years 2011–2015 have been the warmest five-year period on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization, and 2015 was the warmest year for which observational records exist.32 If present rates continue, global temperatures will rise by at least 2°C by the end of the century.33

Box 1.1 WHAT IS A CARBON FOOTPRINT?

A carbon footprint is a measure of the impact our activities have on climate change. Many of our daily activities cause emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs). For example, we produce GHG emissions from burning gasoline when we drive, burning oil or gas for home heating, or using electricity generated from coal, natural gas, and oil. These are considered to be the primary footprint —the sum of direct emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the burning of fossil fuels for energy consumption and transportation. More fuel-efficient cars have a smaller primary footprint, as do energy-efficient light bulbs.

The secondary footprint is the sum of indirect emissions of GHGs during the lifecycle of products used by an individual or organization. For example, the GHGs emitted during the production of plastic for water bottles, as well as the energy used to transport the water, contribute to the secondary footprint. Products with more packaging will generally have a larger secondary footprint than products with a minimal amount of packaging.

Source: Maggie L. Walser, “Carbon Footprint,” in Encyclopedia of Earth, ed. Cutler J. Cleveland, first published July 14, 2010, last revised April 5, 2013, www.eoearth.org/view/article/51cbed2c7896bb431f690448/.

The world’s freshwater resources are also under serious stress. Increased water consumption, rising population, and climate change mean that about 80 percent of the world’s population lives in countries with areas classified as having high levels of threat to water security.34 About 3.4 billion people live in regions with absolute water scarcity.35 Agricultura...