eBook - ePub

Cases and Materials on the Carriage of Goods by Sea

This is a test

- 604 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cases and Materials on the Carriage of Goods by Sea

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Cases and Materials on the Carriage of Goods by Sea, fifth edition, offers tailored coverage of the most commonly taught topics on Carriage of Goods by Sea courses. Combining a collection of legislative materials, commentaries, scholarly articles, standard forms and up-to-date English case law, it covers the major areas of chartering and bills of lading as well as matters such as exclusion and limitation of liability.

Significant innovations for this edition include:

- coverage of blockchain technology and smart contracts in shipping

- coverage of autonomous shipping

- recent developments on the construction of commercial shipping contracts

- recent developments on the transfer of rights and liabilities in the contract of carriage

- tables and diagrams for ease of reading

- discussion of some of the most important decisions by the senior courts of England and Wales, with the most up to date case law included

- references to academic and professional literature for further reading and research

- industry standard form clauses

- reference to important foreign cases

- emphasis on how it is that shipping law operates and is applied in commercial practice

A clear, student-friendly text design with a strong emphasis on research and problem solving. This up-to-date collection of materials relating to the carriage of goods by sea will be of value to students of law, researchers and legal practitioners.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Cases and Materials on the Carriage of Goods by Sea by Anthony Rogers,Jason Chuah,Martin Dockray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter 1

Introduction

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Chartered shipping

- 3 Liner shipping

- Further reading

1 Introduction

The law of carriage of goods by sea has contributed greatly to our understanding of both contract and tort law and is of continuing relevance to the development of commercial law providing, as it does, a steady flow of litigation on essential issues such as the nature of the terms of a contract and the effect of any breach. Since our last edition the flow of litigation has continued and this despite the fact that an unknown, but we suspect large, number of cases are settled via arbitration (which is not usually available to the general public) such as that conducted by the London Maritime Arbitrators Association (the LMAA).

It is a subject that places high intellectual demands upon those who would study it. However, the law of carriage of goods by sea is also important for those who work in the offices of shipping companies and shipping law firms and this direct connection between the intellectual and the pragmatic is part of its fascination. We hope to have achieved a balance so that this edition is useful to the person working in chartering or claims for shipping firms in London or Piraeus (as well as other shipping centres), but also provides an easy access to the law and legal analysis for those engaged in the academic study of carriage of goods by sea or private international trade law at university.

In order to fully appreciate its significance it is important to note that while a knowledge of carriage of goods by sea is essential to understanding shipping law (a term that more accurately reflects the private law nature of what is more commonly called maritime law), shipping law itself is a key element in international trade law. It is difficult to imagine how a study of shipping law (or maritime law if you will!) can be fully complete without seeing it in its context.

The law of carriage of goods by sea is a distinct part of English law. It has special rules that have no direct counterpart in other areas of domestic law. Nevertheless, for the most part, English law relating to the carriage of goods by sea consists only of the application of general common law ideas, together with a small number of important statutes. The basis of the subject is the law of contract but it also draws on the laws of tort, bailment, agency, property and equity.

But if only familiar principles of general law are involved, how can the law of carriage be said to be distinct? One answer can be found in the way in which general legal ideas have been adapted to meet the special features of the sea trade. Shipping is a truly international business: parties to the business may be located anywhere in the world and duties under a carriage contract may be fulfilled in any coastal state. It is sometimes suggested that this international nature brings with it a pressure for international uniformity of the legal rules. This is open to debate since there are also many examples where sovereign states appear to have responded to attempts at international agreement by acting in the national interest. Nonetheless there are examples of law that has widespread, if not complete, application e.g. the Hague-Visby Rules, which we examine later in this book. A significant factor in achieving uniformity is the almost universal use of standard form documents as the basis of most carriage contracts and also the selection of English law and jurisdiction clauses in those contracts, for example in GAFTA (Grain and Feed Trade Association) contracts.

The commercial practice of carriage of goods by sea falls to be performed in special and often hazardous conditions in which it is practically impossible for one party to the agreement to supervise the work of the other from day to day. This factor was clearly instrumental in the development of the sea carrier’s implied duties, including the duty to provide a seaworthy ship and the duty not to deviate from route. It also influenced those parts of the law dealing with the shipper’s duty to disclose the dangerous nature of goods shipped, the master’s powers of jettison and other extraordinary powers conferred on the master in the event of an emergency.

Another notable feature is that shipping is directly dependent on other commercial activities. Contracts for the carriage of goods by sea are not made in commercial isolation. They are typically entered into in order to sell goods or to give effect to a previous sale. This means that contracts for sea carriage are often of direct interest to persons such as buyers or lenders as well as to the original parties to the contract. Third parties may become involved in the carriage of goods in other ways. Even when a cargo remains in the ownership of a single shipper throughout an ocean voyage it is quite possible that the whole or part of the contract (loading or discharging the cargo, for example) may actually be performed by someone other than the party who originally contracted to carry and deliver. This leads to complex questions about who can sue and who can be sued. In the absence of a statute dealing with the particular problem, in English law satisfactory answers to these questions often involve the creative application of ideas drawn from contract (for example, implication of a contract or of a term), tort (for example, recognition or denial of a duty of care), bailment (terms of bailment) or the law of evidence or of damages.

The widespread use of standard forms has already been mentioned. This use amounts in itself to an important feature of the sea trade. It means that much of the law in this area consists of settled interpretations of common clauses and decisions about the terms that can be implied into contracts of carriage in the absence of express agreement. One consequence of the addiction to the use of standard forms is that judicial decisions on the interpretation of standard terms are of wide interest in the shipping industry, which pays marked attention to the law reports. But the wide use of certain forms also means that a judicial decision that disturbs an accepted construction of a document may retrospectively affect many transactions entered into on the basis of that previously accepted meaning. This may influence the willingness of the courts to reverse a settled interpretation. But so too does the knowledge that shipping circles show no reluctance to make amendments to standard forms in order to avoid anything seen as an unsatisfactory precedent.

So much for some of the special features of the trade; can these special features be proved to have influenced the form of what is mostly judge-made law? It would not be easy to show this in some branches of the common law. But the problem is not so great in the case of the law of carriage by sea. For there is a long tradition of looking at this subject as more than a closed set of technical rules. This means that it is not difficult to collect examples of judgments that determine the law only after consideration of the policy that makes the most sense in the special context in which maritime contracts are performed. The well-known decision in Behn v Burness (1863) 3 B & S 751, Exchequer Chamber is a clear example. Other examples include McAndrew v Adams (1834) 1 Bing NC 31, Common Pleas and Bentsen v Taylor [1893] 2 QB 274, CA. We consider these in Chapter 2 and they are not isolated instances.

As we have already noted, the study of the law of carriage of goods by sea is a discrete academic subject but, whilst acknowledging its intellectual status, we should not lose sight of its intimate connection with commercial practice. It is important therefore to set our study of law into its context. The following extract from Stopford, M, Maritime Economics, 2009, 3rd edn, Oxford: Routledge at page 61 will help do this.

The sea transport system

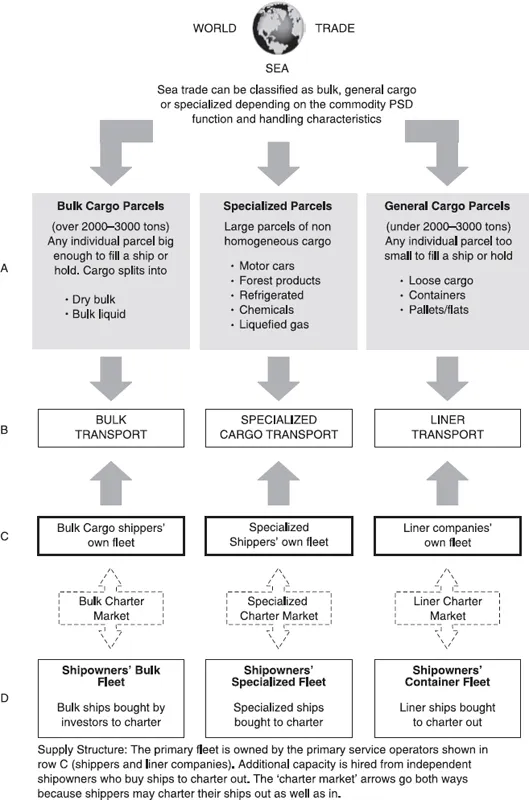

The economic model for sea transport saw that over the last 50 years the shipping industry has developed a new transport system based on mechanization and systems technology. Within this system the economic pressures arising from the parcel size distribution and demand differentiation create the demand for different types of shipping service. Today’s shipping market has evolved into three separate but closely connected segments: bulk shipping, specialized shipping and liner shipping. Although these segments belong to the same industry, each carries out different tasks and has a very different character.

The transport model is summarized below. Starting at the top of this diagram (row A), world trade splits into three streams; bulk parcels, specialized parcels and general cargo parcels; depending on the PSD function for the commodity and service requirements of each cargo parcel. Large homogeneous parcels such as iron ore, coal and grain are carried by the bulk shipping industry; small parcels of general cargo are carried by the liner shipping industry; and specialized cargoes shipped in large volumes are transported by the specialized shipping industry. These three cargo streams create demand for bulk transport, specialized transport and liner transport (row B). The lower half of the diagram shows how the supply of ships is organized. A major distinction is drawn between the fleets of ships owned by the companies moving their own cargo in their own ships (row C) and the ships owned by independent shipowners (row D) and chartered to the cargo owners in Row C. Between rows C and D are the charter markets where rates for transport are negotiated. This is a highly flexible structure. For example, an oil company might decide to buy its own fleet of tankers to cover half of its oil transport needs and meet the other half by chartering tankers from shipowners. The same applies to the specialized and liner markets.

Figure 1.1

The bulk shipping industry carries large parcels of raw materials and bulky semi-manufactures. This is a very distinctive business. Bulk vessels handle few transactions, typically completing about six voyages with a single cargo each year, so the annual revenue depends on half a dozen negotiations per ship each year. In addition, service levels are usually low so little overhead is required to run the ships and organize the cargo. Typically bulk shipping companies have employees in the office for every ship at sea, so a fleet of 50 ships worth $1 billion could be run by a staff of employees, depending on how much of the routine management is subcontracted. In short, bulk shipping businesses focus on minimizing the cost of providing safe transport and managing investment in the expensive ships needed to supply bulk transport.

The liner service transports small parcels of general cargo, which includes manufactured and semi-manufactured goods and many small quantities of bulk commodities malting barley, steel products, non-ferrous metal ores and even waste paper may be transported by liner. For example, a container-ship handles revenue transactions each year, so a fleet of six ships completes transactions per annum. Because there are so many parcels to handle on each voyage, this is a very organization-intensive business. In addition, the transport leg often forms part of an integrated production operation, so speed, reliability and high service levels are important. However, cost is also crucial because the whole business philosophy of international manufacturing depends on cheap transport. With so many transactions, the business relies on published prices, though nowadays prices are generally negotiated with major customers as part of a service agreement. In addition, cargo liners are involved in the through-transport of containers. This is a business where transaction costs are very high and the customers are just as interested in service levels as price.

Specialized shipping services transport difficult cargoes of which the five most important are motor cars, forest products, refrigerated cargo, chemicals and liquefied gas. These trades fall somewhere between bulk and liner; for example, a sophisticated chemical tanker carries parcels a year, often under contracts of affreightment (COAs), but they may take (i.e. individually negotiated) cargoes as well. Service providers in these trades invest in specialized ships and offer higher service levels than bulk shipping companies. Some of the operators become involved in terminals to improve the integration of the cargo-handling operations. They also work with shippers to rationalize and streamline the distribution chain. For example, motor manufacturers and chemical companies place high priority on this and in this sector the pressure for change often comes from its sophisticated clients.

So although the three segments of the shipping industry all carry cargo in ships, they face different tasks in terms of the value and volume of cargo, the number of transactions handled, and the commercial systems employed. Bulk shipping carries the high-volume, price-sensitive cargoes; specialized shipping carries those higher-value cargoes such as cars, refrigerated cargo, forest products and chemicals; the container business transports small parcels; and air freight does the rush jobs. But these segments also overlap, leading to intense competition for the minor bulk cargoes such as forest products, scrap, refrigerated cargo and even grain.

Definition of ‘bulk shipping’

Bulk shipping developed as the major sector in the decades following the Second World War. A fleet of specialist crude oil tankers was built to service the rapidly expanding economies of Western Europe and Japan, with smaller vessels for the carriage of oil products and liquid chemicals. In the dry bulk trades, several important industries, notably steel, aluminium and fertilizer manufacture, turned to foreign suppliers for their high-quality raw materials and a fleet of large bulk carriers was built to service the trade, replacing the obsolete ’tweendeckers previously used to transport bulk commodities. As a result, bulk shipping became a rapidly expanding sector of the shipping industry, and bulk tonnage now accounts for about three-quarters of the world merchant fleet.

Most of the bulk cargoes are drawn from the raw material trades such as oil, iron ore, coal and grain, and are often described as bulk commodities on the assumption that, for example, all iron ore is shipped in bulk. In the case of iron ore this is a reasonable assumption, but many smaller commodity trades are

shipped partly in bulk and partly as general cargo; for example, a shipload of forest products would be rightly classified as bulk cargo but consignments of logs still travel as general cargo in a few trades. There are three main categories of bulk cargo:

- Liquid bulk requires tanker transportation. The main ones are crude oil, oil products, liquid chemicals such as caustic soda, vegetable oils, and wine. The size of individual consignments varies from a few thousand tons to half a million tons in the case of crude oil.

- The five major bulks – iron ore, grain, coal, phosphates and bauxite – are homogeneous bulk cargoes which can be transported satisfactorily in a conventional dry bulk carrier or multi-purpose (MPP) stowing at 45–55 cubic feet per ton.

- Minor bulks covers the many other commodities that travel in shiploads. The most important are steel products, steel scrap, cement, gypsum, non-ferrous metal ores, sugar, salt, sulphur, forest products, wood chips and chemicals.

Definition of ‘liner shipping’

The operation of liner services is a very different business. General cargo consignments are too small to justify setting up a bulk shipping operation. In addition, they are often high-value or delicate, requiring a special shipping service for which the shippers prefer a fixed tariff rather than a fluctuating market rate. There are no hard-and-fast rules about what constitutes general cargo-boxes, bales, machinery, 1,000 tons of steel products, 50 tons of bagged malting barley are typical examples. The main classes of general cargo from a shipping viewpoint are as follows:

- Loose cargo, individual items, boxes, pieces of machinery, etc., each of which must be handled and stowed separately. All general cargo used to be shipped this way, but now almost all has been unitized in one way or another.

- Containerized cargo, standard boxes, usually 8 feet wide, often 8 feet 6 inches high and mostly 20 or 40 feet long, filled with cargo. This is now the principal form of general cargo transport.

- Palletized cargo, for example cartons of apples, are packed onto standard pallets, secured by straps or pallet stretch film for easy stacking and fast handling.

- Pre-slung cargo, small items such as planks of wood lashed together into standard-sized packages.

- Liquid cargo travels in deep tanks, liquid containers or drums.

- Refrigerated cargo, perishable goods that must be shipped, chilled or frozen, in insulated holds or refrigerated containers.

- Heavy and awkward cargo, large and difficult to stow.

Until the mid-1960s most general carg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Table of cases

- Table of statutes

- Table of statutory instruments

- Table of European and international legislation

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Vessel and Implied Warranties as to Her Operation

- 3 Voyage Charterparties, Freight, Laytime and Demurrage

- 4 Time Charters

- 5 Bills of Lading

- 6 Carriage Contracts and Third Parties

- 7 Contractual Liabilities between Carrier and Cargo Interest: The Hague-Visby and Hamburg Regimes

- 8 The Rotterdam Rules

- Glossary

- Index