![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Martin Heidegger on Listening c. 1924

I. AGAINST TRIUMPHAL RHETORIC

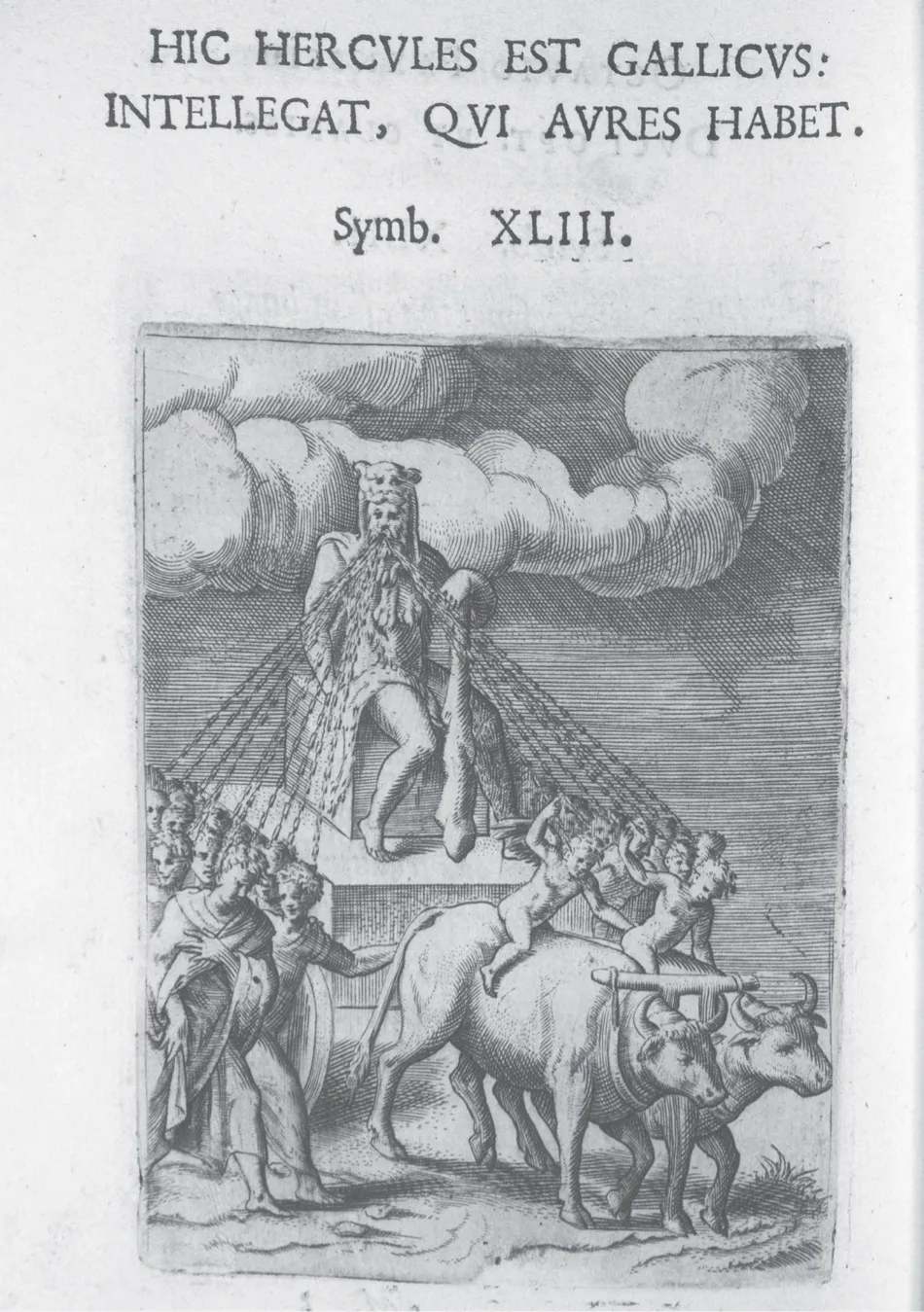

A debilitating commonplace has the history and theory of rhetoric honoring a communicative agent, namely the speaker, at the expense of the listener. In The Emperor of Men’s Minds, for instance, Wayne Rebhorn builds upon the rhetoric emblem Hercules Gallicus to portray the Renaissance orator, like his classical counterparts, as a fighter who triumphs over his listeners.

In their introduction to Adam Müller’s Twelve Lectures on Rhetoric (a German work of political romanticism I will revisit in my discussion of Carl Schmitt), Dennis Bormann and Elisabeth Leinfellner explain, “Because he devotes an entire lecture to listening, Müller deserves special attention for considering a topic almost entirely neglected by earlier writers on rhetoric.” To be sure, they continue, “the classical writers and . . . all theorists up till Müller’s time considered the audience. . . . But listening per se, as an important element in communication, was usually slighted.”1 Then, landing squarely on my topic, Theodore Kisiel, in The Genesis of Heidegger’s “Being and Time,” frames his groundbreaking commentary on the Summer Semester 1924 lecture course by way of Heidegger’s aural perversity. “Rhetoric [according to Heidegger’s reading of Aristotle] is . . . concerned with the convergence of at least three different human powers: being able to speak, to see what speaks for the matter under discussion, and to hear. Almost perversely, Heidegger’s interest in rhetoric gravitates toward the latter power, in which speaking has its end.”2

Figure 1. “Here is Hercules Gallicus: Let him understand who has ears.” Achillis Bocchi, Symbolicarum quaestionum, de vniuerso genere, quas serio ludebat, libri quinque (Bologna: Societatem Typographiae Bononiensis, 1574), Book 2, Symbol 43.

In this chapter I initiate the core of my book project in Martin Heidegger’s vexed material on listening, which has both an academic and an everyday valence. When it comes to everyday experience, this means spending some time in the historical moment when listening reopened onto the scene, partially as a response to the voice of democracy that had become louder via mass media, and newly controversial both in Weimar Germany and beyond. With Heidegger’s phenomenological account of listening, we become more sensitive, in other words, to everyday experiences that helped shape that moment, including most importantly passive- or middle-voiced changes of mind (tied to a critique of liberal democracy), reorientation (tied to Heidegger’s disastrous political philosophy), and obedience (tied in this case to the voice of authority), the latter now broadcasting louder than ever, though not just perniciously, as theologians like Rudolf Bultmann were quick to point out. This chapter at its most fundamental level, then, is about what Heidegger called being-moved—a key term translating Aristotle’s pathos into the German Bewegtsein or Sein-in-Bewegung. And, accordingly, the material in this chapter should seem and feel a certain way, not just appear as a set of abstract considerations linked systematically. Writing about what is unsettling when it comes to the senses and their composition should be in some ways unsettling if the object of study is to appear as such. But methodologically, it’s important to understand how being unsettled in this way, or disoriented, depends upon the world where we find ourselves one way or another. It is not just about biology and some kind of homeostasis at the level of the organism I am. It is not about my passionate hydraulics, or any other type of equilibrium defined by a stable system whether physically mine or psychologically mine. In this case, being unsettled is a worldly affair, including what might appear to be rarefied scholarly considerations, as I hope to demonstrate. Ultimately, scholarship on listening and everyday life, including classroom experience, is all part of the same world, as we like to say, even though it can be increasingly difficult to grasp exactly how so. Here Heidegger helps.

In terms of scholarship, I argue that we reinvigorate the history and theory of rhetoric insofar as we normalize Heidegger’s care for listening. That is, when we can plausibly frame Heidegger’s art of listening in terms of what might broadly be considered the political theology of his moment including the work of Carl Schmitt, Weimar rhetoric transforms our historical horizon. That is where “nonacademic” experience is most obviously brought to bear, as our ways of being (or not) transform. For instance, how does Weimar alter our relationship to the rhetoric of obedience, a word of “non-freedom” that contributes to the German language cluster derived from the word hören, “to hear”—gehorchen, hörig, gehören—as Hannah Arendt reminds us? This is a question that ties together historical considerations that are strictly academic, including the nuances of philology, with everyday life. Listening obediently is something that each of us can do, at the same time that it appears distinctly in our world after authoritarian disasters of the middle twentieth century and in the midst of religious revivals after 1945 that must also contend with state reason. That is to say, inseparable are the scholarship—sanctioned words and interpretation that give us things like post-1945 “history” and “religion”—and the experiences available to me and to others in and beyond this Anglo-European scene, right now.

Or another example. What does the fateful critique of modern, deliberative democracy from both the left and the right force us to reconsider from our own late-modern vantage point, where the appeal to reason cannot be innocent? How does the emergent mass media and its famous Weimar critique reveal how the traditional rhetorical subject and (his) powers can be characterized historically? When we focus on the troubled listener in Weimar Germany, we diagnose the listener’s vanishing point in the history of rhetoric, which traditionally encourages identification with a good man speaking well, and we thereby learn something basic about what binds political constitution and communicative being.

Methodologically following Heidegger, an argument that speaks directly to scholars cannot be distinguished, ultimately, from everyday life. Though the approach to listening varies, these two regions cannot be separated out completely while we imagine, for instance, some detached intellectual history, on the one hand, and my child’s inattentiveness or scientific audiology, on the other. Listening is a phenomenon shared across regions of being; hence, it must be approached carefully as such. In this way, my project is an extension of Heidegger’s work running up to Being and Time (1927) that pursues historical “destruction” on the way to his fundamental ontology, and which turns out to be, in fact, rooted in his work on rhetoric.3 And I offer this methodological fact is no accident, since rhetoric has been defined since its inception as a reorientation in everyday practice, which means in this instance practicing that much better after studying rhetoric; or defined alternatively, as a theoretical reflection, which means understanding better when everyday speaking and listening take shape as the discipline rhetoric, which Heidegger studied so closely and taught so carefully around 1924.

• • •

I begin by unfolding sentence by sentence the key passage from Heidegger’s 1924 Marburg lecture course Basic Concepts of Aristotelian Philosophy.4 It is referred to in Karl Löwith’s transcript as “Aristoteles, Rhetorik II”—namely the second book of Aristotle’s Rhetoric, focusing on the emotions. Published in 2002 in the Gesamtausgabe and translated into English only recently, SS 1924 demands our attention for at least three reasons. First, this Marburg course profoundly shaped a generation of German intellectuals, including Herbert Marcuse and Hannah Arendt (who arrived at Marburg the following semester), and seminar attendees Helene Weiss, Jacob Klein, Siegfried Landshut, Hans Jonas, Karl Löwith, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Leo Strauss, who spoke about a seminar “on Aristotle’s Rhetoric that contained an ontology of the human passions,” where affectability in general and listening in particular was at issue in ways that hit students right where they lived.5 Second, as Kisiel has demonstrated and as I have just mentioned, this lecture course was centrally important for the genesis of that landmark in twentieth-century philosophy Being and Time, which means, thirdly, it represents a significant intervention in the history and theory of rhetoric broadly conceived.

Here is the key passage as it appears on the page translated into English. It is followed by a brief line-by-line elaboration, which outlines most of my key topics going forward through the rest of the chapter.

The being-there [Dasein] of human beings, characterized as λογον έχον [logon echon, “having speech”], is more precisely determined by Aristotle in such a way that in the human being itself, its speaking-being still plays a fundamental role. In being-with-one-another, one can be the one speaking and the other the one hearing. Ἀκούειν [akouein, “hearing”] is genuine αἴσθησις [aísthēsis, “perception”]. Whether or not seeing in connection with θεωρειν [theōrein, “theorizing”] reveals the world in a genuine sense, it is still hearing because it is the perceiving of speaking, because it is the possibility of being-with-one-another [Miteinandersein]. The human being is not only a speaker and a hearer, but is for itself such a being that hears itself. Speaking, as self-expression-about-something, is at the same time a speaking-to-oneself. Therefore, the definition of λόγον ἔχον further contains in itself that the human being also has λόγος [logos] in the mode of hearing this, its own speaking. In human beings, there is a being-possibility that is to be characterized as ὑπακούειν [hupakouein, “hearken, be obedient to, obey”]. Aristotle exhibits this basic phenomenon through concrete contexts of being-there themselves, through peculiar phenomena that are touched upon in Book 1, Chapter 13 of the Nicomachean Ethics, and that Aristotle designates as παράκλησις [paraklēsis, “incitement”], νουθέτησις [nouthetēsis, “admonition”], ἐπιτίμησις [epitimēsis, “reproach”] (1103a1). All of these modes of natural speaking-with-one-another carry in themselves the claim that the other does not merely take notice of something, but takes something up, follows something [etwas befolgt], reflects on something. The other repeats that which is spoken in such a way that in repeating he listens to it, such that the following results: in the being of the human being as concernful lies the possibility of listening to its speaking. (72)

(1) To start with, not λογον έχον as a rational creature, but rather a speaking-being. In Marburg’s Neo-Kantianism, recalls Gadamer in his interview for my coedited book Heidegger and Rhetoric, logos was just “reason,” but through Heidegger’s reading of Aristotle, Gadamer grasped, to his great surprise, “that logos has something to do with speaking” and thus the way was opened for a serious consideration of rhetoric. As Gadamer describes it, this moment was a basic reorientation of the sort that drew students in droves to the lectures of the “hidden King” who was rescuing Aristotle from historical obscurity on the way to a complete reorientation of philosophy, including what it meant to sit in that very lecture hall listening to one’s world transform by way of philosophical exegesis, of all things.

(2) That said, speaking is not primarily a matter of ποίησις (poiēsis, “personal mastery, creative autonomy”), or willful imposition on an audience (Wittgenstein would similarly argue there is no such thing as a private language). Instead, speech is a function of Miteinandersein (“being-with-one-another”) and hence it must be conceived more fundamentally as a human capacity in its “passive” or “pathetic” dimension. Rhetoric, in other words, should be considered δύναμις (dunamis, “capacity”) primarily and then secondarily a τέχνη (technē, “art” or “technology”).

(3) As opposed to detached seeing in a certain mode of theory (θεωρία), “hearing” therefore designates a more basic aesthetics of our shared world.6 But in 1924 and a bit later in Being and Time, Heidegger will take pains to point out this doesn’t mean physiological hearing as one of the five senses that lends itself to empirical measurement. “What we ‘first’ hear is never noises or complexes of sounds, but the creaking wagon, the motor-cycle” (§164), the voice of the friend or enemy. In 1927 Heidegger gives us this formulation: “hearing constitutes the primary and authentic way in which Dasein is open for its ownmost potentiality-for-Being—as in hearing the voice of the friend whom every Dasein carries with it. . . . Being-with develops in listening to one another [Aufeinander-hören], which can be done in several possible ways: following, going along with, and the privative modes of not-hearing, resisting, defying, and turning away” (§163).

(4) Crucial for Heidegger’s return to a technical rhetoric is the critique of the tradition cited at the opening of this chapter where ethical weight is placed squarely on the speaker, who stands in for us as the active subject of rhetoric, while the abject audience stands in for our vulnerabilities, which include listening, learning, feeling, absorbing, obeying, and so on. Heidegger would have none of the school discipline that supposedly dominated the Hellenistic and early Middle Ages, returning instead to rhetoric as a concrete guide for the interpretation of Dasein: “The human being is not only a speaker and a hearer, but is for itself such a being that hears itself,” and in 1927 this would mean the call of conscience.7

(5) Not solipsism but exactly the opposite—namely, being-open in the listening modes carefully distinguished across Aristotle’s practical treatises, which include the Rhetoric, Politics, and Ethics, through the transitional text de Anima into what we normally bracket off as the natural scientific treatises on Physics and The Motion of Animals, which situate being-open humanly in the context of being-moved generally. Hence, “Grundbegriffe Der aristotelischen Philosophie,” not in the end “Aristoteles, Rhetorik II.” The passion-action nexus situates specifically human modes of engaged listening: “In human beings, there is a being-possibility that is to be characterized as ὑπακούειν.”8

(6) Typically, in 1924 Heidegger situates Aristotle’s Rhetoric in a continuum of life processes whereby epideictic, or ἐπαινός (epainos, “praise”) and ψόγος (psogos, “blame”) rhetoric, appears not as persuasive technique we learn in school, but rather as an inherent psychic capacity touched upon in ...