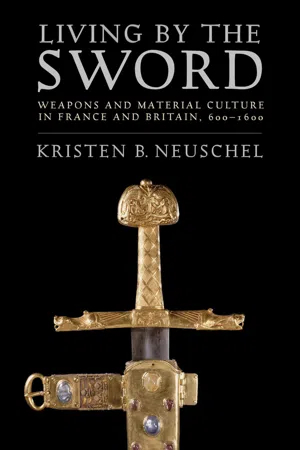

CHAPTER 1

Swords and Oral Culture in the Early Middle Ages

In a pathbreaking 1936 essay, J. R. R. Tolkien set scholarship on Beowulf on a new course when he argued that the poem should be considered as a piece of literature and not simply mined for data about the migration-era societies it purportedly depicts. The poem, Tolkien asserted, does not describe actual societies but rather is an “echo of an echo,” a rendering of a long-gone world many generations later. Whatever historical meaning there is to be had, he argues, is found in the poem as a piece of literature, in the emotions, the longings, the grief, evoked by the story as it is being told. Hence, we should not dismiss the dragon, who guards the buried hoard near the end of the tale, because we believe it to be a commonplace—its meaning obvious as evidence of a medieval imaginary we think we know already. Whatever we may think we know, Tolkien cautions, there are actually very few dragons in literature of this epoch. Like any important character, this one merits attention. We must ask: what is this dragon (and other dragons mentioned in the tale) doing here, what does it mean? We should set aside assumptions and condescension and, instead, should listen, really listen, to this echo.1

Tolkien’s breakthrough was to recognize Beowulf as literature before scholarly work on oral culture made it easier to see the structure of storytelling and use of language peculiar to oral traditions and thus to expand our definition of what constitutes “literature.” The barriers to appreciating the work as art, in Tolkien’s day, included the fragmented structure of the story, which contained many digressions or interruptions of other tales, such as the story of Ingeld, the best known of these sidebars. Subsequent scholarship about Beowulf has not allowed all of Tolkien’s perspectives to stand, such as his view that the poem was composed in the age of Bede, meaning roughly the first half of the eighth century.2 The consensus now is that the composition of the poem is more recent, much closer to the date of the extant manuscript (ca. 1000) than Tolkien thought. In fact, recent scholars have suggested, the only poem we really have is the one preserved in the British Library, the product of a poet or poets and his (perhaps) later interpreters, including the two scribes who edited, amended, and produced the actual text that we do have.3 Thus we have an interpretive problem that amplifies Tolkien’s original point: if the poem is an echo, why was a scribe determined to preserve it, “hear it,” so many centuries after the events it purports to describe, and what vision of the past was the poet creating?

Here, I will in turn echo Tolkien’s plea regarding the dragon as I consider evidence of swords from the early medieval past. Unlike Tolkien and his dragon, we have remains of actual swords from the early medieval centuries with us in the present, and evidence of how they were saved, exchanged, buried, and memorialized, sometimes in documentary traces. Swords were expensive, high-prestige weapons. We do not know precisely how rare swords were among fighting men, though we know that some warriors fought only with the less expensive spear. We also know that, along with spears, other kinds of cutting blades such as long knives or seaxes, wide single-bladed weapons, were also common. But much of the story of how swords were valued lies, as with the dragon, in what we can retrieve of their users’ imaginations, and of the symbolic world of which swords were a part. Material evidence, documents, and stories must all be weighed together.

Yet neither material remains nor textual evidence is transparent to our gaze. Interpretation can be difficult partly for technical reasons: for example, the task of making philological comparisons within a small body of surviving sources to prise meaning from a unique text, as Beowulf is. In addition, as disciplinary protocols and interpretive stances have changed over time—dramatically, in some cases—evidence has been lost. Archaeologists practicing a century ago had unearthed artifacts with ambitious methods we now regard as reckless. They also brought rigid notions about sex and gender with them to their sites, and did not consider jewelry (such as brooches) to be worn by men. Often, evidence from these sites was not preserved in ways to make reinterpretation by later investigators possible, thus we may never know the full range of grave goods in many cases.4

Much of the interpretive challenge we face, however, is inherent in any effort to make sense of fragmentary evidence. The limited surviving evidence from the early medieval centuries means that the bits we do have must help build a basic narrative of the period, but which then, in turn, becomes the context in which we interpret each piece of evidence. With works of literature, this circularity means we interpret it in relationship to its context, which it illuminates, and only after conjecturing when it was written. In addition, the richest sources, like Beowulf, are relatively late—the ninth or tenth centuries or even later—and most scholars find it irresistible to extrapolate backward from them.

Narratives of medieval history, moreover, tend to be weighed down with the burden of accounting for origins, with seeing eventual nation-states or national cultures or “peoples” in artifacts or texts from the fifth or eighth or tenth century.5 Rich texts like Beowulf or The Song of Roland are virtual national monuments, certainly national myths.6 One scholar describes the investment modern English readers have in Beowulf: “we view and re-view [it] over years, even over generations, with something like the care we give our own personal pasts, and what those will mean for our future.”7 In other words, we inevitably respond to these tales not only as myth, but as our own myth, and do not easily recognize when we are conflating our myths with ones the texts advance. When encountering swords in documents or poems or in images or within graves, we experience familiarity instead of a sense of rift with the past.8

In what follows, I will sketch the history of the manufacture of early medieval swords, then discuss evidence of those swords’ symbolic lives revealed by archaeological finds, namely grave goods and our reconstruction of rituals that accompanied their deposit. Then I consider written evidence of swords, particularly in early wills that record both the bequeathing but also the prior circulation of a sword among allies and kin. Finally, I turn to literature, to Beowulf and its near-contemporary, The Battle of Maldon, to explore the roles those poems ascribe to warriors’ (and monsters’) swords. We cannot rigidly separate these different sorts of evidence; all are frustratingly incomplete, and one genre allows us to pose interpretive questions of others. In addition, the world of fiction—to the degree these poems are fictional—inevitably responded to and added its imaginative weight to the possibilities of human experience, including the significance of swords to the men who wielded them.

Early medieval literature is filled with references to the aesthetic qualities and the mysterious origin of swords and their constituent parts, as well as to their power to strike fear, to wound, and to kill. The uncanny properties of blades alone spurred much poetic effort: a blade was lightning bright, deadly, unpredictable; or the rippling marks produced by the smith’s hammer were imagined (borrowing from another craft) as woven silk, or as rushing water or writhing serpents. The making of the blade could even supply an image for the very work of the warrior: in one poem, fighting men are described as “war-smiths.”9 Spears and axes as well as defensive weapons like helmets and chain mail are also celebrated, but swords are clearly at the center of the linguistic imagination of early medieval warriors. Literary sources evoke an aesthetic appreciation of swords along with a sense of their utility as weapons and their power, as actors in their own right, to create memory and myth. These different meanings would not have been experienced as entirely separate. The ways in which they shaded into each other can be traced in literature but also by examining how swords were manufactured, used, and exchanged in early medieval society.

Europeans of this era could not have imagined a distinction between objects of beauty and those of powerful technology like swords. Both were the products of individual craft labor, and “art objects” in such geographically mobile peoples always connoted accessible wealth and generally consisted of fine metalwork; gold armbands, jewels, drinking vessels, helms, and weapons could all be rewards for loyal service as well as representations of a leader’s power. Not surprisingly, many memorable swords of which we have any trace from this era were both objects of art and weapons at the same time.10 The best blades, however elaborately decorated, were most effective as weapons precisely because they were artful: individually crafted from unique materials by a smith skilled in metalworking techniques and able to improve and innovate.

It is likely that high-quality sword blades (as opposed to wholly iron-made low-quality blades) were initially produced in relatively few locations and traded across distances.11 Some of the finest steel blades, probably produced at one site on the Baltic coast, wound up as far away as modern Ireland, in the wake of Norse settlement. They can be identified by the inscription “Ulfberht”—seemingly the Germanic name of the smith. The early blades with this inscription were made from steel produced by a more expensive method than was used in Europe, thus no doubt procured via Norse trade in the Volga basin from Iran, Central Asia, or India. But the swords bearing this mark were produced over about three hundred years, long after the trade of Asian steel was cut off. Such was the reputation of these blades that subsequent generations of craftsmen traded on the identity of the original maker, even though they produced blades of decidedly lower quality. Well-made European blades were traded across borders, too, to the east as well, in violation of proscriptions, such as in Charlemagne’s capitularies, which are no doubt evidence of that very trade.12

The most skilled European smiths twisted small bits of steely iron produced by their smelting process together with pieces of inferior iron, then forged them together with other like bundles of mixed carbon contents to form a blade with adequate steel distributed in it. Steel edges were sometimes also welded on. Known as “pattern-welded” blades, when finished, they were distinguished by a wavy pattern or water-like ripples that appeared on the surface of the metal, somewhat like the so-called “damascene” blades made from Iranian or Indian iron. Modern artisans have estimated that a pattern-welded blade took some two hundred hours of work time to complete.13 Well-made blades and great smiths inspired much lore, which we can glimpse in surviving texts. For example, in a laudatory poem about the battle of Brunanburh, a Saxon victory over Vikings and Scots in 937, the swords wielded by the Saxons are referred to by a particular finishing technique (being milled down in a particular way after forging) that would have produced superior weapons.14 The technology of producing fine blades was rare, and it was celebrated.

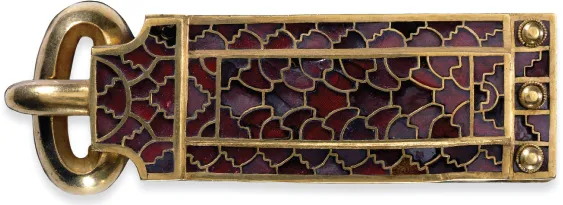

But swords did not consist merely of blades; they were then, and remained, composite artifacts. Indeed, just as blades varied, one from another, so did the other components of swords: the hilt, made up of guard, grip, and pommel, and the scabbard and sword belt, and all of their fasteners. The designs, especially of hilts, relied on local craftsmen with expertise in other metal and jewel-working skills. The sword in the famous ship burial at Sutton Hoo in Essex, England (ca. 625), for example, was decorated with gold and cloisonné, with garnets inset into both concave and convex surfaces, while a surviving piece from about 250 years later, known as the Abingdon sword, has an hilt of engraved silver mounts depiciting the four evangelists; the engraving is set off by inlayed niello (a black sulfide of silver), the work of a master silversmith.15 Scabbards, too, had metal fittings, which required one kind of expertise, but also used wood, leather, sheepskin, and cloth. A fine sword and its accoutrements, in other words, was the product of a number of different craftspeople and their specialized skills; the wonder of a great sword in its day lay in the blade, whose construction was the most unaccountable, but also in the combination of expertise and artistry that produced both the whole and each of the parts. Those combinations could be reworked, a worthy blade given a new hilt or scabbard, for example. Swords circulated as both new and remade objects.

PLATE 1. The artistry of Sutton Hoo artifacts. The partially reconstructed sword hilt (approx. 6.5 cm. x 9.5 cm.) and the buckle from the sword belt (7.3 cm. x 2.3 cm.) found in the Sutton Hoo ship burial. Both buckle and sword hilt are decorated with gold and garnet cloisonné. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

So as swords themselves changed when a new hilt was attached to an old blade, or a new scabbard created for an existing sword, they also changed hands, through gift, inheritance, burial, and conquest. The biggest mistake we can make, standing at a distance as we do from this thicket of imagery around swords, is to see swords as static objects of reverence rather than in motion in the warrior lifeworld, alive because they changed materially and also by means of their “lives” in different human hands. Even swords deposited in graves had lives and afterlives, and their significance must be interpreted, not assumed.

Grave goods, including swords, other weapons of all kinds, jewelry, and clothing, have been found at burial sites in what is now France and England (as well as Germany and the Low Countries) dating from more or less a four-hundred-year span, from the end of the fourth century, when Roman power began to withdraw from northern Europe, to about 700 CE. In most locales, the deposition of grave goods tailed off in the eighth century, not because elites had embraced Christianity, which mostly happened earlier, but because relatively more settled political conditions called for new kinds of rituals and sites for burial, which now became closely associated with church buildings. Inhumations with goods slowly were deemphasized relative to the sacred spaces built aboveground.16

Furnished inhumations were not the typical practice in Roman communities, so the very existence of such cemeteries in western Europe seemed a kind of identity marker for “barbarian” peoples to early twentieth-century archaeologists, whose methodology led them to interpret particular styles of artifacts as evidence of specific “cultures.” The movement of peoples from east to west across Europe in the migration age, in their eyes, could be traced through archaeological finds. One lingering outcome of this kind of thinking has been the assumption that the presence of a sword “meant” a warrior who had been buried with his weapon.17 Other weapons found in graves, by similar logic, also signaled warrior burials. So, sword or ax or knife were straightforward markers of status or function, and nothing more.

Historians have revised these interpretations by establishing the contingent, porous nature of barbarian groups and their long-standing interactions with Roman power. Together with recent archaeologists, they have reinterpreted data from a number of grave sites to demonstrate that the point of weapons deposits in graves was equally contingent—that is, closely related to immediate political conditions on the ground. We now believe that swords, weapons, and other goods were selected and placed in individual graves deliberately, for a reason, not merely reflexively because they were the belongings of the dead person.

First, it is clear that swords were less common in graves than they would have been in actual use by living fighters. Indeed, fewer than one-quarter of all the cemeteries on the northern continent that have been excavated to date contain any sword burial at all. Of those that do, more than three-quarters have only one or two swords in the entire site.18 Data from pagan Saxon cemeteries in England, surveyed in 1989, reveal that 18 percent of all inhumations with goods (including about 47 percent of i...