![]()

1

THE EUCHARIST

To be more specific about the way in which the Gospels enable us to rediscover the historical Jesus, it is clearly necessary to carry out a literary examination of the sources, which will be the object of the next chapters. Here, strongly convinced that these ancient events have a present importance, we take things up more from a distance—or from up close—by starting from Christian life today, based on the memory of Jesus Christ. The chosen starting point is the Eucharist, which implements the sacramental aspect of the Scripture, where the Gospels have a special place. Two effects follow from this; one on the participants in this Eucharist, the other on the inspiration and the word of God.

I. Structure of the Eucharist

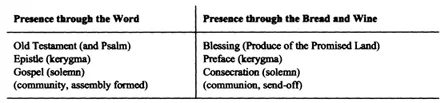

Traditionally, the Eucharist is made up of two parts: a liturgy of the Word, and a properly sacramental ritual. However, it is a rather complex whole. At the risk of oversimplifying, a model of it in two symmetrical phases is proposed here, so as to put into relief the importance of Scripture.

1. The starting point consists of a song, which announces a divine horizon, but it is immediately followed by a penitential ritual, where everyone admits to being a sinner, namely in one way or another maladjusted. These two elements create a tension.

Next comes the proclamation of three scriptural passages. Typically, there is a passage from the Old Testament (some ancient rites integrated two of them, one drawn from a historical book and the other from a prophet), followed by an orchestration with a psalm, that is to say, an actualization through song; next there is an Epistle and a Gospel. This arrangement has a precise meaning: the Old Testament represents the time of hope for sinners; the epistle announces that all is fulfilled in Jesus Christ; the Gospel, preceded by a solemn greeting by the one presiding and followed by a salutation “Praise to you, Lord Jesus,” presents Jesus Christ, who speaks here and now, with the congregation being turned to the east, in remembrance of the dawn of the first day of the week, which can be seen also as an eighth day and would represent the new creation. This solemnization of the Gospel explains why it is placed after the Epistle, whereas the chronology would require the opposite, since Jesus lived before the proclamation of the kerygma by the apostles.

The function of the homily that follows is to make current all the Scriptures, that is to say, to confirm that they are present The prayers and the “holy kiss of peace” that come next indicate that the congregation is created and connects itself to a more vast body, in space and in time: reconciliation and personal expression.

2. The second part is also the second phase of the real presence, where we are going to recognize three moments, parallel to the three readings indicated.

There is initially the blessing of the bread and wine, which are presented in a small quantity. This parallels the reading of the Old Testament of the first part. The formula used is Jewish in origin; historically, it deals with the basic produce of the Promised Land. The Bible points to two feasts of note: the first is the Passover celebrated by Joshua beside the Jordan at the time of the entry into Canaan of the Israelites; it was marked by the renewal of the covenant, by the cessation of the manna of the wilderness, and by the beginning of the consumption of the produce of the land, that is to say, the completion of all their hopes. The second reference, moreover, one that is much more clear-cut, is the Pentecost, as a feast of the first fruits of the produce of the land. In the two cases, the possession of the completion of their hopes is stressed.

Then comes the preface, which is a solemn kerygmatic proclamation: it repeats in a lyrical style the essential content of the Epistle and ends up with the Sanctus, an echo of the proclamation of the presence of God in the sanctuary (Isa 6:3); the congregation has become a sanctuary.

Finally comes the consecration, surrounded with historical reminders: as in the case of the Gospel, the celebrant takes the place of Jesus Christ in pronouncing the words of the Last Supper (“This is my body”) as they are reported by Paul, namely with the command to repeat it. That therefore takes place here and now. This phase concludes with the approval of the community and the solemn act of the “breaking of the bread.” This is moreover the name of the Eucharist in the New Testament. In fact, the act does not consist in the first place of preparing for the distribution, but of expressing the death of Christ; it is by his death that he becomes food. The history and the humanity of Jesus are consequently made present, which underlines that it is not a matter of a philosophy. The celebrant represents at the same time Jesus Christ and the congregation, so that his action has a double dimension: on the one hand, Jesus gives his life as a ransom, and on the other, the Christians, because of their sins, contribute to his being put to death.

The loop thus being complete, the distribution takes place. Then the congregation is dismissed, perhaps sent to visit the sick or on mission. In any case, it is a return to the world of everyone, with its realities and its idols.

This organization can be summed up in a diagram:

Schema of the Eucharist in Two Parallel Columns

To this particularly verbal structure, it is necessary to add some signs indicating the setting, since it is question of a feast. We can mention music, carpet, and flowers, as well as a banquet. It is more important to point out the presence of those deceased: relics and icons demonstrate this, making them part of the same congregation. A frontier between life and death is therefore abolished. “Life has triumphed over death,” says St. Paul.

Lastly, we must not forget that participation in this Eucharist is restricted to the baptized; sometimes there is, at the outset, a ritual with water that brings to mind Baptism. There is therefore a preliminary educational process that closes with a welcoming of the community. The congregation is co-opted, without hereditary right.

Traditionally, Baptism and Eucharist are described as “sacraments,” a term of Latin origin whose Greek equivalent is “mystery.” Broadening the definition somewhat, we will speak here of sacramentality to refer to an official ecclesial action that makes Jesus Christ present and introduces a congregation into the ultimate eschatological kingdom.

The first issue that arises is evidently to establish whether what the Church thus carries out has a clear connection with what Jesus said and did. In the Acts of the Apostles, there is a reference to the baptized “in the name of Jesus”; then the community, which lives in unanimity, is faithful to the breaking of bread. There is even mention of a Eucharist celebrated by Paul at Troas, which lasted all night from Saturday to Sunday, up to the arrival of daybreak.

We detect some traces earlier. In the Gospels, Jesus receives John’s baptism; according to John 3:22, he himself baptizes. In regard to the Eucharist, there are two indications: according to John 6:48, 54, Jesus enigmatically declares: “I am the bread of life. Anyone who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life.” But according to the last supper of the Synoptics, he expressly instituted the ritual of the bread and wine. However, everything is carried out in the setting of the annual Passover, which creates a difficulty, because the ritual described above has nothing of the paschal, neither from its weekly frequency nor from the bread and wine, since the principal element of the paschal ritual is the immolated lamb, together with the unleavened bread and the bitter herbs.

Finally, the passage that best recalls the Eucharist is the account of the Emmaus pilgrims, since it includes Scripture, the announcement by the stranger that all has been fulfilled, the breaking of the bread, and the realization that Jesus Christ is present. However, it is a matter of the risen Christ, and not an act of the pubic life of Jesus.

In a general way, the New Testament only reminds us of the institutions in passing, and never deals with them in detail. The eucharistic rite described above is compatible with the texts, but it is not possible to deduce it as such. There are two possibilities then: either it was developed from the New Testament and consequently is an ecclesiastical creation that owes little to Jesus; or it is a matter of rites that Jesus knew—and transformed. Several indications favor the second hypothesis. Let us first consider Baptism: John the Baptist proclaimed a baptism for the remission of sins; Jesus himself was baptized; when it became necessary to replace Judas, someone was sought who had been, with the others, a witness of everything “since John’s baptism”; then, at the time of Pentecost, Peter and his companions baptized “in the name of Jesus Christ” for the remission of sins. To put it plainly, the new baptism is none other than the baptism of John, duly transformed in the name of Jesus Christ.

In regard to the Eucharist, to which Baptism is the access, we see less clearly its origins in the New Testament, since John the Baptist did not eat the bread and did not drink the wine. However, we can call on the Jewish context of the time: there existed a body, a more or less unified network of reforming communities, called Essenes, who considered themselves the true covenant. Its members were chosen or co-opted, not by right of birth; the admission of neophytes took place through a baptismal education, whose conclusion was the participation in a community meal, called “purity,” in which there was a rite of bread and wine taken in a small quantity, in memory of the first fruits of successive Pentecosts (text C). The meaning of the first fruits easily becomes eschatological: to have access to the produce of the new harvest can simply symbolize access to a new kingdom.

Two indications of a more sociological nature in favor of the preexistence of rites can be added: on the one hand, it is not realistic to presuppose that Jesus would have created something from start to finish just before his death, since it cannot be imagined how the disciples, scandalized by his death, would have retained from it anything that would be useful; according to John 21:1–3, Peter and his companions decided, after a succession of exceptional events, to go fishing, to return to everyday life, since they had families to feed. On the other hand, we see in the New Testament great discussions on the importance or not of circumcision for the admission of pagans into the community. Was Baptism sufficient for admission to the covenant, as the Essenes required, or was it necessary to follow the custom in use since Abraham, which defines Israel as a people by circumcision? The question is not easy and, by analogy, it would be difficult to admit that the further introduction of a rite as important as the Eucharist could have taken place without leaving the least trace of a debate.

Let us sum up, by bringing up two problems:

1. First, through the sacramentality, the Eucharist considered in this way refers to realities surrounding Jesus: before him, by the Old Testament; after him, by the actualization of the resurrection (kerygma); between the two, we detect the echo of Jewish realities of his time, which have given a form. However, a problem remains, that of the connection between the Eucharist and the Passover: to give the name of a Jewish feast to the Sunday of the resurrection corresponds to nothing that can be identified. Besides, it is not certain that the use of unleavened bread— an evident Passover sign— would have been primitive, since the Easterm churches ignore it, and since it is difficult to think that it would have been quietly suppressed: the ancient writings show no trace of a discussion on the question. In any hypothesis, the identification of Christ with the paschal lamb is well founded in the New Testament, but this should not be confused with the origin of the rite.

2. Next, Scripture, duly proclaimed, has the effect of actualization, which is evident, but it must be emphasized that the Gospel, which sets out the public life of Jesus, is presented as the word of the Risen One to the assembly. The narrative ceases being a report in order to become an icon. There will be room to wonder whether such a presentation is a credit to the style of these accounts, or, conversely, whether the wording has not been influenced by a liturgical usage of this type. We can already observe that the beginning of the Second Gospel has the appearance of a rubric, with a complete entitlement that is not found elsewhere (Mark 1:1): “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, Son of God.” The underlying problem is that of the origin of the Gospels. It is certainly not enough to say that they were necessary for Christian preaching, since all the epistles (except perhaps 2 Peter, reputed to be late) and all the Christian authors up to Justin speak of the death and resurrection of the Christ, but with almost very few exceptions, they ignore the whole of the doings of the public life of Jesus, or at least do not take account of them in their writings.

There is however a preliminary question. The feet that the old texts could be understood assumes that modern people are not fundamentally different from the contemporaries of Jesus. This is not the place to wonder whether it is a matter of an act of nature, or if the centuries of Christianity have molded something like a Homo christianus that would be the quintessence of the Homo sapiens of the specialists of prehistory. We will limit ourselves here to affirming that the Bible speaks in the same way always and everywhere. Some important consequences result from this. In particular, the sending on mission by the Risen One is permanent, with a setting of sacramentality (Matt 28:19): “Go therefore, make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them … And remember that I am with you always, to the end of the world.” If we come back to the Eucharist, we must emphasize that it involves a very precise concept of the human being. Let is briefly develop this point.

II. Song and Sin

Baptism frees from original sin. However, Paul, who does not hesitate to proclaim loud and clear the results of the mission confided to him, indicates that he is able to devise what is good, but not to carry it out; he recalls that he had been left a “thorn in the flesh,” that kept him from boasting. In a similar way, Peter was set up as head of the community by Jesus, but at the same time, the Gospels take the trouble to emphasize all his blunders.

What exactly is it all about?

Paul affirms (Rom 5:12,18): “Just as by one man (Adam) sin entered the world, and by sin, death, and thus death has passed to all, since all have sinned, … in the same way the work of justice of (me alone (Jesus Christ) obtains for all the justification that gives life.” Paul returns on several occasions to this opposition between Adam and Jesus.

It is necessary to pause a while on the sin of Adam as it is described in Genesis. He received the command not to eat from a certain tree, under pain of death. But the tempter, represented by the serpent and with Eve mediating, emphasized that it is out of jealousy that God had imposed a ban: eating this fruit would allow them to become like a god, “knowing good and evil,” in other words, to decide what is good or evil. The result is disastrous. Adam discovers that he is naked. Then he tries to hide himself from God and utters an essential admission: “I was afraid because I am naked.” Finally, he leaves his innocence, but accuses Eve. To sum up, Adam, a failed little god, accuses others, and finds himself destined for death. This fall has an odor of existential death. Such is the work of the tempter. We can complete it with the case of Cain. He is jealous of his brother, and God puts him on guard against himself “while sin is crouching at the door”; finally, he kills his brother, but struggles to own up to it when apparently he has violated no explicit precept Like Abel, he has made blood flow, but in an unruly manner.

The doctrine of original sin comprises maintaining on the one hand that all humans are predisposed to go through the experience of Adam—and do so—and on the other hand, that Christ has atoned for this curse, or, as Heb 2:15 says, “has freed all those who, during their life, were held in slavery by the fear of death.” In a more colorful way, Rev 12:9 speaks of the dethronement of “the great dragon, the primeval serpent, called the devil or the Satan, the seducer of the whole world and the accuser of our brethren.” There is in fact a superposing of the collective dimension and individual sins. The prophets always attack the people’s sin, whose source is idolatry, and there is solidarity between the generations. The ritual of the Day of Atonement (Yorn Kippur) transfers the sin of the people to the scapegoat; it nullifies the effects of the accidents of history, but it does not erase the memory of them, which accumulate. Even the Essenes, who want to restore the covenant under a sectarian form, are conscious of the weight of the inheritance. The Rule of the Community, discovered at Qumran, gives some information on the ritual for the admission of neophytes; the priests recall the benefits proceeding from God, then the Levites enumerate the sins committed over the centuries, and finally the neophytes declare: “we have sinned, we and our ancestors.”

In Christianity, the central affirmation of the resurrection of Christ according to the Scriptures restores an area of humanity where this weight is lifted. Its frontier is marked by Baptism, but in the outside world, human societies, while fascinating, remain powerless to give life, and even tolerate the deviants. However, the specific Christian remains submerged in the real history of nations and its absurdities, but the Eucharist renews the passage from Adam to Jesus Christ, that is to say, it recreates an assembly or a communion; this is a trace of eternal life on earth. Thus, by the resurrection of “the first-born of a multitude of sisters and brothers,” suffering, injustice, and death cease being a threat, and as a consequence the actual events take on a new meaning, as they sing at Easter: “O happy fault, that has merited us such a Savior.”

In the biblical accounts, the most noteworthy sinner is David. A gallant warrior, he succeeded in federating all the Israelites, installed the capital of the kingdom in Jerusalem, and repulsed various neighboring enemies, among them the ever-present Philistines. While his armies were involved in battle, at the end of a siesta he caught sight of a beautiful woman who was bathing herself; this was Bathsheba, wife of Uriah the Hittite, an officer away at battle. He had her come to him and he lay with her. On learning that she was pregnant, he had Uriah return from the front so that he might be joined to his wife and the pregnancy attributed to him, but Uriah refused to do so out of solidarity with his comrades in arms. David then sent for him and gave him a message for Joab, the general in command, in which he ordered him to put Uriah in a dangerous outpost so that he might be killed. This was done, and David formally married Bathsheba at the end of a period of mourning. Then the prophet Nathan came to him to ask his advice on an affair in which a rich proprietor had seized the only lamb owned by a poor shepherd. David then declared angrily that the rich man deserved to die, and Nathan said to him: “You are that man.” And David, without any circumlocution, recognized himself a sinner against God (and not against Uriah or Bathsheba), and, we can add, refrained from accusing Bathsheba, who had taken a bath close by: unlike Adam, he did not accuse the woman.

The incident is instructive in more ways than one. Initially, David, an all-powerful king, acted in an underhanded manner, which is somewhat contradictory. Then, the story told by Nathan functions as a parable, which can be taken as a simple anecdote or as a personal message that uncovers the dissimulation; we will later go back over this mechanism, essential in the New Testament. Lastly, the sin is committed with regard to God: like Adam, David wanted to decide what is good or evil—according to the caprice of a king—but he had to hide.

However, David is the venerated ancestor of the Messiah, according to the prophets’ constant assertion; his house, for a moment fallen, will be restored. It could be argued that all these authors hold on to the memory of King David, an elect of God and one anointed by the prophet Samuel, and that the details of his life have only been composed later. Such an objection is trivial, because the unanimous postbiblical tradition maintains his status as ancestor of the Messiah and the same is true of the New Testament. In developing the genealogy of Jesus, Matt 1:6 indicates imperturbably that “David was the father of Solomon, by the wife of Uriah.” But the main point is elsewhere. In combining several verses of the Old Testament, Paul cites “the testimony of God” about David (Acts 13:22): “I have found David, son of Jesse, to be a man after my heart, who will carry out all my wishes.”

This choice is all the more remarkable since Saul, the king who preceded David, is removed for what seems to be a trifle (1 Sam 15:1–32): Saul had received from Samuel, in the name of God, the order to exterminate the Amalekites and all their possessions, but he saved the best part of the booty, claiming that it was intended for the offerin...