![]()

1. Introduction

Richard Hodges, William Bowden, Oliver Gilkes and Kosta Lako

Toward evening we arrived at a village called Livari, a corruption, it is thought, of Vivarium, from the fisheries in the lake, which here finds an outlet into the sea by means of a river. By the people of the place the lake is also called Boïdoperes. At Corfu the village is known as Butrinto or Vutzindro, but in the country itself we found these names unknown, a source of confusion, which caused us much difficulty. On the opposite side of the water is a rocky height, with remains of walls, which mark the site of the ancient Buthrotum, the celsam Buthroti urbem of Virgil. As we were embarking to cross to Corfu, I said to a Turkish official who was standing by, ‘Now we are leaving Turkey?’ ‘Yes,’ he replied, ‘now you are going to Europe’ (Fanshawe Tozer 1869: 232–3).

Introduction

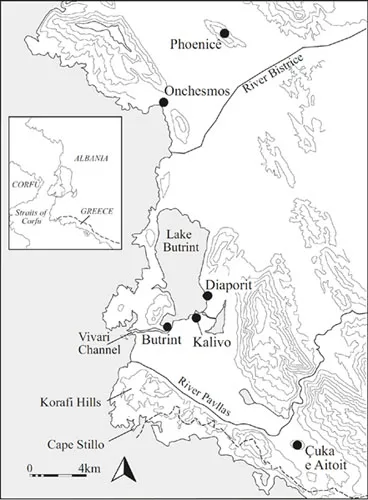

Butrint sits at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, commanding the sea-routes up the Adriatic Sea to the north, across the Mediterranean to the west, and south through the Ionian islands. Like ancient Dyrrhachium (modern Durrës) to the north, it also controlled a land-route into the mountainous Balkan interior. The abandoned ancient and medieval port is located 3 km inland from the Straits of Corfu in south Albania (Fig. 1.1). For much of its long history it occupied a hill on a bend in the Vivari Channel, which connects the Straits to the large inland lagoon of Lake Butrint. A narrow plain, formerly a marsh, separates the channel from a band of hills to the south, along which runs the present frontier between Albania and Greece. Immediately east of Lake Butrint, a range of hills and low mountains rise up to 824 m, effectively creating a basin around the ancient city and the inland lake.

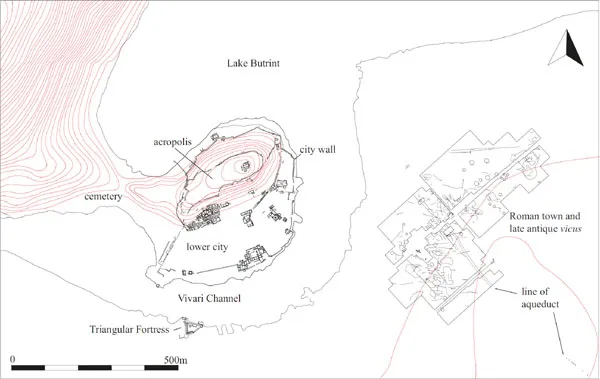

The walled city, designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1992, covers an area of c. 16 ha (Figs. 1.2–3), but geophysical survey on the eastern side of the Vivari Channel shows that at times in antiquity Butrint covered as much as 30 ha (see Chapters 5 and 6). The walled city comprises two parts: the acropolis and the lower city. The acropolis is a long narrow hill, approximately 200 m long and 60 m at its widest, that rises up to 42 m above sea level at its east end; its sides are accentuated by a circuit of walls that separate it from the natural and artificial terraces gathered around the flanks of the hill. The lower city occupies the lower-lying contours down to the edge of the Vivari Channel. Remains of a cemetery are recorded on the spine of the hill running west from the acropolis (Ugolini 1937: 174; Budina 1988), but its extent is unknown. The most obvious monument outside the city walls, on the opposite side of the channel, is the Triangular Castle, which after 1572 became the nucleus of the early modern settlement (Leake 1835: 95; Karaiskaj 1980: 33–5). Beyond the fortress to the east, opposite the walled site, there are substantial remains of late Republican to Byzantine date. These, as we shall see, form part of the Roman town and, later on, the late antique vicus.

History of discovery

Cyriacus of Ancona was the first antiquarian to visit Butrint. The Renaissance collector paused here on 26th December 1435, and recorded two inscriptions that he quite probably removed (Ugolini 1942: 223), as well as drawing sketches of the ruins. Many subsequent visitors mentioned the port, but the first major description of Butrint’s topography is by Colonel W. M. Leake, who visited Butrint in 1805. Leake arrived by boat from Saranda, and described his arrival at Butrint thus:

As we approach Vutzindró, the water becomes muddy, and in the bay is almost fresh. This bay is very shallow on the northern side, and the bar at the mouth of the river will even now, when the water is still at the highest, but just admit of the entrance of καíκαí, or small coasting vessels. We row three or four miles up the river, through a plain once perhaps the property of Atticus, a friend of Cicero, and now peopled with horses from the neighbouring village. We then arrived at the Vivári, or more vulgarly Livári; that is to say the principal fishery, which is on the left side of the river, at its exit from the lake, nearly opposite to the peninsula which was anciently occupied by Buthrotum. The only buildings at the Livári are a ruined house of Venetian construction, and near it an old triangular castle, occupied by a dirty bilibásh of the Vezír, and fifteen or twenty soldiers (Leake 1835: 95).

Fig. 1.1 Butrint and the surrounding region. (IWA)

The following year, Leake’s rival at the court of Ali Pasha, the French diplomat François Pouqueville, also visited Butrint, writing a description that was similar to that of Leake:

On the south side of the channel, communicating between that lake and the sea, is constructed the modern Venetian fortress of Buthrinto, and on the opposite side are the ruins of old Buthrotum … These ruins show an acropolis or citadel, and the Roman town inclosed within a double wall, containing fragments of both Greek and Roman architecture. But, in the walls of the acropolis are preserved foundations of the highest antiquity, consisting of vast blocks without cement (Pouqueville 1820: 34–5).

There were other visitors as well. An anonymous tourist inscribed his initials and a date, AD 1796 P. A. M., on a Byzantine fresco on the acropolis (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Ugolini file [hereafter MCR Ug] 35), and during 1819 the French artist Louis Dupré visited in the company of the British High Commissioner on Corfu, Sir Thomas Maitland, in order to meet Ali Pasha. He was unimpressed with modern Butrint: ‘The fortress, if one can really apply that term to such a miserable tower, is armed with three cannon of mixed calibre …’ (Dupré 1825: 10). However, the ruins of the ancient city moved him to speculate on future possibilities:

Fig. 1.2 Overview of archaeological remains at Butrint and on the Vrina Plain. (IWA)

Fig. 1.3 Aerial view of Butrint. (BF)

Butrint, ancient Buthrotum, capital of the Chaonians, is today a tumble of ruins, but once in a more heroic and less barbarous age was a place of renown. It is without doubt that, one day, explorations of the ruins will bring forth a great wealth of discoveries that have been covered for all these centuries by the curtain of night (Dupré 1825: 9–10).

Dupré took the opportunity during a duck hunt on Lake Butrint, organised by the Vezir, to sketch Ali being rowed through the reeds of the lake shore (Fig. 1.4).

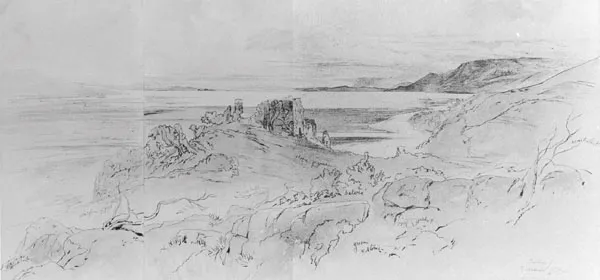

Throughout the 19th century Butrint was visited by tourists and artists, who found it easy to make the short trip from Corfu. Henry Cook, a British lithographer, visited in 1822, to draw the ruins by the Channel. As part of a series covering Corfu, Cook produced two prints. The first, entitled ‘The Aga’s House’, depicted (with a little artistic licence) the Venetian Triangular Fortress (see Fig. 6.23), while the second, called the ‘The Robber’s Castle’, shows a view westwards along the Vivari Channel with a watch-tower on the acropolis (Fig. 1.5). A further, somewhat romanticised, view of the Triangular Fortress was included by George De La Poer Beresford in a set of lithographs, Scenes in Southern Albania, in 1855. However, the best known artist of this time to record Butrint was Edward Lear. Lear excluded Butrint from his famous 1848 itinerary, but during his residence on Corfu during the later 1850s visited a number of times (Noakes 1979: 319–21), sketching Butrint on 7th January and again on 7th March Fig. 1.6). He made a journey to Tepelena in April of the same year and described his arrival in Albania in a letter to his sister Ann:

We had a perfectly quiet passage across of only 3 hours and anchored in the little harbour of Trescogli [modern Ksamili] – enjoying all the afternoon on making drawings – below the tall white heath all in bloom and having a comfortable dinner and quiet night. Early on the 3rd we found some woodcutters horses by the shore, and as there was no wind to take us on to Santi Quaranta, the proper place of landing to go to Delvino, we hired them and set of walking all along the lake of Butrint – which I did not draw, because it is within a 2 hours sail any day (Edward Lear: Letter to his sister Ann, 23/4/1857 Unpublished; excerpt reproduced courtesy of Vivian Noakes).

Other visitors of this era included regular parties of huntsmen and tourists. The Irish aristocrat Arthur Kavanagh visited on a number of occasions in his yacht, Eva. One such trip was sufficiently memorable to prompt him to write a book (Kavanagh 1865). Like Lear, his party put ashore at Ksamili. He employed local beaters to flush game birds and boar out of the thick undergrowth. Despite being born without arms and legs, the adventurous Kavanagh was a crack shot and an early amateur photographer (Steele 1891). His book is illustrated with lithographs made from the photographs he took on this occasion, which are the earliest known photographs of the immediate environs of Butrint.

Fig. 1.4 Ali Pasha on Lake Butrint, sketch by Louis Dupré, 1819. (Private Collection)

The Italian Archaeological Mission

It was perhaps the descriptions of these earlier visitors that led to the arrival of the Italian Archaeological Mission, directed by Luigi Maria Ugolini, in 1924. Ugolini’s mission was sponsored by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the specific request of Mussolini (Petricioli 1990: 268–74; Gilkes and Miraj 2000). The ministry was concerned to enlarge Italian political influence over the fledgling state of Albania and, alarmed by the presence of a French Archaeological Mission at the Graeco-Roman city of Apollonia, selected the young Fascist prehistorian Ugolini to make a survey of the country’s archaeology (Petricioli 1990: 274; Gilkes and Miraj 2000). In 1924 Ugolini made a journey through Albania, visiting many archaeological sites and ending up at Butrint (Ugolini 1927: 153–4). The following year Ugolini returned to begin a major project, which he launched at the Epirote hilltop site of Phoenicê, situated 30 km north of Butrint at the ancient limit of Lake Butrint (Fig. 1.1). In his four seasons of excavations at Phoenicê, Ugolini excavated the Hellenistic ‘treasury’, several Roman cisterns, and an early Christian basilica, as well as recording standing Roman remains within the village at the foot of the hill (Ugolini 1932a).

In 1928 Ugolini moved the mission to Butrint, initially camping on the acropolis. Here he launched a colossal and well-publicised campaign of excavations on and around what was, at that time, a largely bare unwooded hill (Fig. 1.7). In addition, his colleagues were encouraged to survey the surrounding region to record archaeological sites of all periods.

Ugolini was explicit in his intentions: according to Virgil, it was at Butrint that Aeneas had stopped before sailing on to Italy to found Rome, and Ugolini therefore wished to tighten ‘the spiritual chains between Rome and Butrint’ (Petricioli 1990: 284; cf. Ugolini 1937: 12). Between 1928 and 1943 the mission carried out a great campaign of excavations and surveys, which increasingly became entangled in the complicated political relations between Albania and Italy. The ambition of the project, however, was undoubtedly curbed by Ugolini’s death at the age of 41 in October 1936, although the mission continued on a slightly reduced scale under the direction of Luigi Marconi (who died in an aeroplane crash in 1938) and Domenico Mustilli. When the Greek army overran the area in the late autumn of 1940, the excavations had been only partially published. Investigations resumed after 1941, but ended with Italy’s withdrawal from the Axis alliance in 1943. The projected series of five volumes of Albania antica was eventually reduced to three, with the excavations of the Theatre and Baptistery appearing in an abridged form in Ugolini’s Il mito d’Enea. Gli scavi in 1937 as well as in earlier reports and essays (Ugolini 1931; 1934; 1935).1

Fig. 1.5 The Robber’s Castle, print by Henry Cook. (Prints and Drawings, British Museum, London)

Fig. 1.6 Butrint, sketch by Edward Lear, 7th March 1857. (The Gennadius Library, Athens)

Fig. 1.7 Luigi Maria Ugolini (front centre) in the Theatre, 1931. (MCR Ug 80)

At Butrint, as at Phoenicê, Ugolini’s interests extended well beyond the narrow ideological imperative of discovering the foundation phases of the ancient city. With his background in prehistory, he encouraged innovative work on the palaeolithic and earlier prehistory of the area by Luigi Cardini (Gilkes forthcoming; Francis forthcoming), just as he took an explicit interest in the archaeology of the Byzantine phase (Ugolini 1933; 1936) and its history (evidenced by an unpublished manuscript of transcriptions of medieval texts pertaining to Butrint in the Museo Nazionale della Civiltà Romana).

Post-war Butrint

Following the withdrawal of the Italian Archaeological Mission, Butrint was effectively abandoned until the late 1950s. Photographs show that much of the site became overgrown, despite the presence of a site guard from approximately 1948. Renewed scientific interest in the site was led by Dhimosten Budina, one of the first members of the Albanian Institute of Archaeology at its foundation in 1948.2 Budina was trained as an archaeologist in Moscow, and on returning to Albania in 1956 was despatched to Saranda to establish a regional office responsible for Butrint, Phoenicê and other archaeological sites in the region. In 1958–59 the Institute of Archaeology collaborated with a Soviet archaeological mission in an excavation of the nearby site of Çuka e Aitoit. Members of the project staff lived in the acropolis castle constructed by Luigi Ugolini at Butrint. In May 1959 Nikita Khruschev visited Albania and travelled to see Butrint (Fig. 1.8). The visit caused the Albanian government to construct and surface a road from Saranda to Butrint, and to clean the archaeological site. From this time, and for the next 30 years, the Institute of Archaeology periodically undertook excavation campaigns, supported by the Institute of Monuments, which sustained Ugolini’s programme of monument conservation and repair. Neritan Ceka and Gjerak Karaiskaj published major studies of Butrint’s multi-period fortifications (Ceka 1976; Karaiskaj 1976a; Karaiskaj 1976b; Karaiskaj 1980; Karaiskaj 1983). In 1975–76, Kosta Lako undertook a large excavation in a previously unexamined area on the interior of the Hellenistic wall between the Great Basilica and the so-called Gymnasium (Lako 1981). In 1982, Skender Anamali, Dhimosten Budina, Selim Islami and Aleksandër Meksi led a high-profile summer training excavation that led to renewed excavations of the Baptistery and Theatre areas, as well as excavations on the acropolis and on the extramural cemetery to the west of the city and a survey of the Great Basilica (Meksi 1983a; Budina 1988). Lako pursued the Triconch Palace excavations throughout the 1980s (Lako 1990), while his colleague, Astrit Nanaj, investigated the acropolis (Nanaj 1985), and Dhimeter Çondi and Budina explored the so-called Gymnasium (continuing the earlier investigations by the Italian mission) (Çondi 1989).

Fig 1.8 Nikita Kruschev, Enver Hoxha and Nexhmije Hoxha (right to left) at Butrint, 1959. (Arkivi Kombëtar i Filmit, Tirana, Albania)

In 1990, with the beginnings of a democratic movement in Albania, the Institute of Archaeology initiated a number of colla...