This is a test

- 274 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

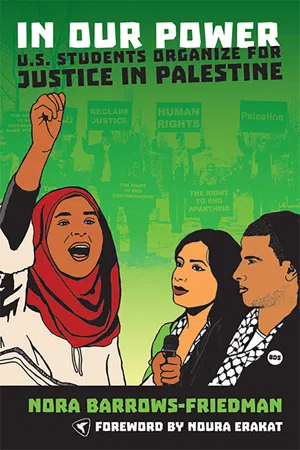

In the years following Israel's 2008–9 "Operation Cast Lead" attack on the Palestinians of Gaza, a new kind of student movement emerged on U.S. campuses, in support of the idea that Palestinians should gain the full exercise of their human and political rights within their historic homeland. In 2013 and early 2014, journalist Nora Barrows-Friedman crisscrossed the United States interviewing the young activists who form the core of this new student movement, and their voices ring out strongly from every page of this book. In Our Power reveals the rich political legacy these students are building on campuses all around the country.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access In Our Power by Nora Barrows-Friedman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Ideologies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Inspired to Act

Why does one person sitting at a table have the ability to travel when he wants and not have to plan around permits and roadblocks, and why does another have to wonder what it feels like to be free?

—Kristian Davis Bailey, Stanford University student

First row: Alex Abassi, Hassan Abdinur, Nashiha Alam

Second row: Leila Abdul Razzaq, Max Ajl, Hazim Abdullah

I met Amanda Ghannam, a political science and sociology student at the University of Michigan at Dearborn, at a popular Palestinian sweets café near campus on a bright October morning in 2013. I asked her to tell her story, and she began by explaining that neither she nor her Palestinian parents had ever been to Palestine although all of her grandparents were born there.

“Growing up, you hear about [Palestine],” she said. “There’s that knowledge in the back of your mind, but until you choose to dig deeper into it, you don’t know all the details of course—you just know that the place you come from is not free.”

Ghannam admitted that she didn’t know that much about Palestine organizing before she got to college. “I had this impression that there wasn’t a whole lot I could do at my age, and maybe not even much I could do in my life, until I attended the national Students for Justice in Palestine conference in 2012—which I happened to hear about by chance, over Twitter or something. And because it happened to be in Ann Arbor, it was right here, I figured that I’d go. It was a huge eye-opener, and I can honestly say it changed my life in a very real way.”

Here she broke into a wide smile. “I didn’t know before I attended the conference that so many people were working so hard,” she said. “It was like a breath of fresh air, meeting all those people who were so committed towards the same goal, and finding out there are concrete actions we can take as American citizens.”

I had e-mailed Ghannam before I visited the Detroit area; regional organizers recommended her to me because of her superb activist credentials. At the café, she shared her conflicted feelings about participating in this book. “I have dreams about Jerusalem,” she said, softly. “I hear all these stories about activists being denied entry, or being harassed at the checkpoints, and I know it would be easier for me because of my American passport, but when I got your e-mail I was very hesitant to put my name on this project.” She told me that her biggest fear is that she’ll never get to visit Palestine.

However, Ghannam went on to say, these kinds of public projects help legitimize the work that student activists have been doing. I asked her if she wanted to change her name in this book, in order to protect her identity when she attempts to enter her homeland. “If I change my name in this book to get into Palestine, they win,” she answered. “Zionists have been co-opting and chipping away at Palestinian identity for years. And intimidating people into staying silent about solidarity, activism, and heritage is one way that they continue to chip away at that identity. To speak up without fear is my form of resistance. I can’t give up on that.” I was—and remain—moved by Ghannam’s courage, and I’m immensely grateful for her decision to be included in this book.

The global struggle for Palestinian rights is growing as tolerance wanes for Israel’s policies of occupation, segregation, and discrimination. And, like many historical battles for human rights, students are at the forefront of this rapidly expanding movement.

Despite branding itself as the region’s lone democratic state, or hyping up its glamorous tech industry, or beckoning members of the LGBTQ community to experience the “gay haven” it would like to represent, Israel exposes its deceit when the surface is lightly scratched.

Palestinians were first subjected to Israel’s systematic injustices when they were expelled from their homes and land in the late 1940s, as Zionist militias swept through historic Palestine, destroying more than 500 villages and towns and forcing more than 750,000 indigenous Palestinians into dozens of refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan. Today, Palestinian refugees are the largest population of forcibly displaced persons in the world, totaling more than 7 million. They are not allowed to return to their homes of origin simply because they are not Jewish.

Palestinians inside the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip are forced to live under absolute control by the Israeli government and its occupying military. In the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, water, education, agriculture, residency, and property ownership rights are systematically refused to Palestinians while illegal Israeli settlement colonies continue to spread across the hillsides and valleys. Israeli settlers—backed by throngs of Israeli police—routinely storm Palestinian homes and evict entire families, throwing their belongings onto the street, and moving into these homes hours later. At least 27,000 Palestinian homes and structures have been demolished in the West Bank including East Jerusalem since 1967, as Israel’s plan to Judaize the land continues unabated and unrestrained by various international laws and conventions.

Indigenous Palestinians in Jerusalem are not granted citizenship, but, rather, an Orwellian status as “foreign permanent residents” whose residency rights can be revoked at any time. Israel’s illegal wall in the West Bank—condemned by the International Court of Justice in 2004, which recommended it be torn down immediately—cuts deep inside Palestinian land, annexing the settlements on top of the richest water sources and fertile land areas and leaving Palestinian villages, towns and cities separated from one another, from clinics, employment opportunities, schools, and religious centers. The wall and the settlements have chopped the West Bank into dozens of isolated bantustans, only accessible to one another through hundreds of Israeli military checkpoints.

In Gaza, 1.7 million Palestinians—80 percent of them refugees and 60 percent under 18 years old—are subjected to widespread isolation and economic subjugation as Israel controls the land, air and sea boundaries, infrastructure, electricity, and the ability of people to leave and return at the Gaza-Egypt border. Since 2006, Israel has imposed a blockade and siege on Gaza: all imports, including basic medical supplies and construction materials to fix ailing and destroyed infrastructure, are controlled by Israel, and all exports have virtually stopped, completely debilitating Gaza’s economy. Gazan fishermen are routinely shot at by Israeli naval forces if they fish more than three nautical miles from the shoreline, and Gazan farmers are fired upon if they venture “too close” to the “no-go zone” along the boundary with Israel, a vague and ever-changing strip encroaching into Palestinian agricultural lands.

Meanwhile, across occupied Palestine, Palestinian children, women, and men are routinely arrested, detained, mass incarcerated, put in administrative detention—indefinite detention without charge or trial—prevented from seeing lawyers or family members while in jail, and tortured and abused by Israeli soldiers and security guards who use American-made equipment and surveillance technology. Indeed, Israel is the largest recipient of U.S. aid in the world, and its occupation is financed, supported, and fortified by American citizens, politicians, and corporations.

And inside Israel itself, Palestinian citizens of the state are living under dozens of discriminatory laws intended to separate the privileges of the population and favor Israeli Jews over non-Jews in housing, education, land ownership, and social services.

Legendary American prison abolition activist and scholar Angela Davis has linked the systems of mass incarceration in the United States to Israel and beyond. In a speech she gave in London in 2013, Davis admonished the transnational security corporation G4S, which provides services and equipment to Israeli prisons. Davis said:

We’ve learned about the terrifying universe of torture and imprisonment that is faced by so many Palestinians, but we’ve also learned about their spirit of resistance, we’ve learned about their hunger strikes and other forms of resistance that continue to take place behind the walls.

…Racism provides the fuel for the maintenance, reproduction and expansion of the prison industrial complex. And so, if we say, as we do, abolish the prison industrial complex, we should also say abolish apartheid. And end the occupation of Palestine.

When we have, in the States, described the segregation in occupied Palestine, that so clearly mirrors the historical apartheid of racism in the southern United States of America, especially when we talk about this to black people, the response is often ‘why hasn’t anyone told us about this before? Why hasn’t anyone told us about the signs [describing restrictions of movement] in occupied Palestine? And about the segregated express auto-highways? Why hasn’t anyone told us this before?’1

Shocked and outraged at the injustices against Palestinians half a world away, students in the United States have historically been drawn to solidarity movements for Palestinian rights. Today, that movement is wildly diverse, strategic, and more popular than ever. By relentlessly challenging the dominant narrative and making sustained protest of Israeli policies more mainstream, students are changing the way this country thinks about Israel.

For Palestinian students, some who are third- or fourth-generation refugees, joining Palestine and Arab-centered activism and cultural organizations can be an empowering way to connect with their heritage and the ongoing struggle for their rights. Most families are encouraging of this kind of student activism, but some parents, as students mention in this chapter, are wary that if their children join Palestine solidarity groups, the U.S. government and powerful Zionist organizations could target them for surveillance and harassment.

These are legitimate fears. The U.S. government keeps tabs on citizens who descend from the Middle East, while FBI informants infiltrate mosques and political activism groups around the country. Israel-aligned organizations and Islamophobic groups smear Arab and Muslim activists and label any criticism of Israel as anti-Semitic.

Many students of Palestinian descent are afraid that if they sign their names to statements, or speak out during public events, or participate in projects such as this book, their name could be added to a list that would prevent them from visiting family in Palestine in the future.

Meanwhile, Jewish-American students are becoming more involved in the struggle for Palestinian rights, and can clearly articulate the difference between Zionism and Judaism. Support for Israel among American-Jewish youth is steadily declining, sending Zionist organizations clamoring for new recruits and new opportunities for propaganda.

It is not always easy to become an activist, many students told me. But they say that organizing for Palestinian rights between classes and grueling exams is worth it—that standing up for human rights is an important part of one’s ongoing education as a global citizen.

Personal histories of struggle

In Albuquerque, Jadd Mustafa, a student at Central New Mexico Community College, told me that his involvement in Palestine solidarity activism was catalyzed after he went to visit Palestine in 2005 with his family.

Because his relatives in Palestine have West Bank identification cards, they cannot travel outside of the occupied West Bank unless they have permits from the Israeli authorities to do so. “During the visit, it was made clear how things weren’t the same as far as where we could go as a family—the coastline wasn’t an option, because [my family who live there] had West Bank IDs,” Mustafa said. On a later trip, Mustafa’s father was prevented from traveling to Jerusalem and present-day Israel, “places you should be able to visit because of the religious and cultural significance,” he added, with frustration in his voice.

Amal Ali is a history major at the University of California, Riverside. She is an energetic leader in the campus’s Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) group, and has been deeply involved in the two-year-long push to have the university pull its investments from U.S. companies that profit from Israel’s human rights violations.

Ali’s father’s family was expelled from Palestine during the Nakba in 1948, and her mother’s family was pushed out two decades later during another wave of expulsion following the 1967 War. Her grandparents on both sides fled to Jordan, where both of her parents grew up before coming to the United States for college educations in the 1970s.

Ali said that when her father became involved in the Arab-American community as a university student, they organized demonstrations for Palestinian rights with a passion similar to that of Ali’s generation. “They had rallies; they raised their voices and shook the boat a little bit at their respective campuses. They also were very big on doing things [such as] going through the processes of writing to their congressman and making sure that they contacted their representatives in a way that they couldn’t do in Jordan as displaced citizens,” she said. Ali added that she grew up thinking she was Jordanian because all of her grandparents lived in Jordan, but said that she knew there was “something different about my identity because my dad took us to these strange rallies where they would chant ‘Free, free Palestine.’

“At one point I asked, ‘So, Dad we’re Jordanian, right?’ Because somebody at school asked and he said, ‘No. We’re Palestinian.’ And he sat me down in his lap and told me the whole story of our identity and our existence. And at that point I was like, ok, I’ve got to find something out about this. So using whatever limited Internet [access] I had at the time, I tried to do my homework, tried to figure out what I could read at the grand old age of eight years old. So those are the very early beginnings [of my interest in activism].”

Ghassan Hussein is a respiratory therapy graduate from San Joaquin Valley College in southern California. He was born in the West Bank, came to the United States as a child, and then returned to his village, Turmosayya, for middle school and high school. He said that during his high school years in the West Bank, when he was exposed to the violence of Israel’s occupation, he realized that he could bring his personal experiences back to the United States to encourage campus activism:

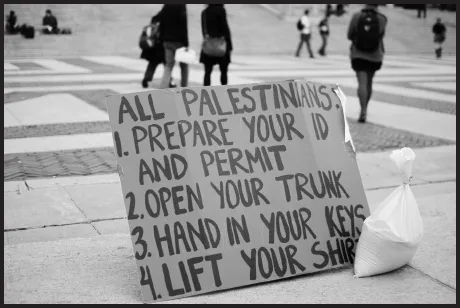

Columbia SJP mock checkpoint, 2010. (Photo by Andra Mihali)

From stun grenades to tear gas, to rubber bullets [being shot] and almost hitting me, to Israeli harassment in and out of my village, to checkpoints, being banned from traveling, basically being stripped of basic human needs and human rights—I experienced all of that there. When I left Palestine after high school and came to the U.S. to pursue college, I realized I had to dig deeper and find out more about what was going on. I needed to educate myself more and also start spreading awareness about the situation.

I discovered that hardly anyone was paying attention. Even Arabs from my community—even Palestinians—do not know simple things that are happening in Palestine. And that, to me, was really, really devasta...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Back Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword by Noura Erakat

- Preface

- 1. Inspired to Act

- 2. Building from History

- 3. Creative Tactics

- 4. The Campus as a Battleground

- 5. Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions: A Growing Movement of Justi

- 6. Empowering Scholarship

- 7. Intersecting Struggles and Common Causes

- 8. Advice to Student Activists

- 9. Defining Solidarity

- Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author