This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

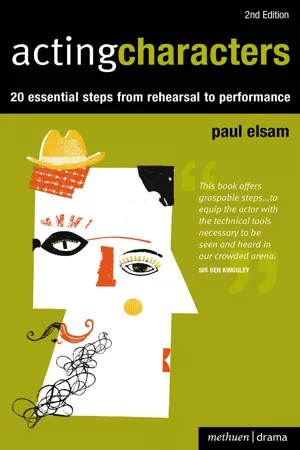

Paul Elsam's Acting Characters is an introductory handbook for the aspiring actor, compiled of twenty steps grouped into six sections to help create, present and sustain a believable character in most circumstances. Fundamentally practical, the book avoids the heavy discussion of theory that often accompanies books on the subject, looking instead at the essentials of how to use different voices and body language to convey character.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Acting Characters by Paul Elsam in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Acting & Auditioning. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

section 6: inner life

This section is exlusively to do with what goes on inside you – thoughts, emotions, sensations, memories – all linked as they are to the conscious and subconscious mind. We’re going to explore how an actor can use knowledge, skill and imagination to create a sense of inner reality during rehearsal and performance.

Actors use emotion and imagination to varying degrees depending on their preferred style of acting (e.g. Storyteller or Inhabiter); on the working methods of their director; and on the training they have received. Work on the inner life of a character can be highly rewarding, not least because it’s here that truly spontaneous discoveries are most likely to occur.

In this Section we’ll be adding the final four new Tools to your repertoire, all of which are forged from the teachings of Stanislavski.

Tool Number 17 – The Magic What If? – explores that most basic yet powerful of mental activities: the act of stimulating your imagination.

Tool Number 18 – Energising your Character – examines the benefits of mapping your character’s psychological journey through a play, using objectives, barriers and possible actions.

Tool Number 19 – Imagining Sensations – discusses the importance of sensory awareness in performance and considers how this can best be developed.

Tool Number 20 – Generating Emotion – analyses the importance of stimulating emotion using psychological spurs such as revisited memories.

Once, when I was rehearsing the role of twin Eddie for a tour of Willy Russell’s Blood Brothers, I inexplicably found that I was crying – sobbing, actually. In the scene the seven-year-old Eddie was saying goodbye to Mrs Johnstone, a woman who (unbeknownst to Eddie) happened to be his natural mother, something clicked inside me and, in a room full of actors and stage management crew, I found I was sobbing like a baby (or rather, like a seven-year-old child). In subsequent rehearsals this never happened again, but the memory of that emotional outburst always stayed with me, and with the actor playing Mrs Johnstone, so that the scene forever retained a sense of childish loss as its undercurrent.

In the previous Sections of this book we’ve gone into considerable detail exploring what behavioural signs are there for you to recognise and use. These things – and in particular THOSE LINT PADS – give you, the actor, a huge repertoire from which to draw as part of your task of telling stories about the humanimal. It’s no accident that this Inner Life section comes last. You should now be pretty fully versed in the outward expression of the inner life of a person. Remember, too, that we’ve already explored the psychological reasons why people’s behaviour changes in each of the THOSE LINT PADS areas.

You’ll notice a slight change in format in this final Section. The Acting Tips have been incorporated into the main text simply because we’re now looking specifically at the skill of acting (so you could say that everything you’re about to read represents Acting Tips). Also, each sub-section now includes exercises and activities within the text, rather than at the end. This means that as a reader you can exercise your imagination as you go along, which better suits the spirit of this Section. After all, as you sit, seemingly innocently reading this Section, how many of the people nearby know what you’re really up to? There really is a minefield in this area. Views are polarised and intense. In one corner are those who believe that inner life is the single most important aspect of acting. Here you’ll be likely to find Lee Strasberg, Michael Chekhov and Konstantin Stanislavski, and in support, acting greats such as Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, Daniel Day Lewis and Al Pacino. In the other corner are the advocates of what we might call Representational acting – acting which seems real but does not require constant and intense emotional experience to be effective. Here we might find Laurence Olivier, Michael Caine, Dame Judi Dench – and a younger version of Konstantin Stanislavski. Even Brando, preparing for his Godfather role with cotton wool tucked inside his cheeks, seems to occupy a more central position along with Anthony Hopkins.

So who is right? Neither side? Both sides? It’s surely a matter of opinion. But I do believe this: technique and instinct should always be working together. Blending these two things so that you can’t see the join is, for me, the essence of great acting.

So I’m going to focus on offering some ideas on exploring the inner life of a character. As ever, they mostly spring from the mind of Stanislavski. He recognised (and experienced) the need for actors to have a practical process to help them overcome the inherent unreality of acting: the requirement to act on cue between, say, 7.30pm and 10pm; the demand to do so nightly for perhaps as long as a year using the same words every time; and the unremitting falseness of a situation whereby you stand on a stage trying to ignore both your audience and the Assistant Stage Manager perched in the wings.

Tool No. 17: The Magic What If?

The final key to keeping your acting as truthful as possible is, of course, active use of your imagination. Interestingly, active imagining is used a lot these days by those other performers who work under heavy psychological and physical pressure – e.g. professional sportsmen and women. Sprinters and tennis players use it (though they may call it visualisation). They visualise that moment when they reach the tape in first place or when they deliver a match-winning first-serve ace. And it works (usually).

Actors imagine too, of course. It’s at the very heart of what they do. To be a good actor, you need to be open and responsive to your imagination. Stanislavski’s most simple concept was also I think his most effective – the so-called ‘Magic If’. What if –? This simple phrase is a wonderfully direct challenge to the part of you that enjoyed playing games of imagination as a child. In An Actor Prepares, Stanislavski sets up a hugely powerful ‘what if’ which locates the threat of a deranged would-be killer just outside the room. Wherever you are as you read this, imagine that now you (not a character, but the real you) are at risk of attack from a person nearby who has the means to kill you. What do you feel? What, specifically, is your new main emotion?

Rather cleverly, that no longer becomes the key issue. Infinitely more important is the question, ‘What do I do?’ How do you ensure your survival? What about loved ones nearby? What can you do to protect them? What if the would-be killer hasn’t seen you? If you keep still they may just go away. Use your imagination now to focus hard on that. As you do so, your mind will be whirring with thoughts and feelings, but your body will be pretty well still. You will be experiencing inner life.

Of course, you don’t have to be still to experience inner life. Indeed, Section Three of this book explored in some detail how even minor tensions and movements give out clues. You should have learned, through that earlier Section on the body, what the external signs of a person’s thoughts and feelings are. What we’re considering now is how an imagined stimulus (an image or a memory, for example) can spur you on to physical action. We’re now going inside the character to discover how things you imagine while in character help to prompt a spontaneous physical expression.

Back to the deranged would-be killer for a moment. You’re keeping as still as possible in the hope that they won’t see you and will go away. You just want them to go away. What are you feeling? Who cares, frankly. You just want them to go away. But they’re still there, edging around, peering in your direction. You hear a shout or a bang. Have they seen you? If they have, what now? You need an escape route. How well do you know this place? How far is it to safety and help? Would it be safer to sit it out and try to reason with them? How are you feeling? (Not great, you think, but can we discuss that later?)

Life isn’t always that dramatic, of course – though in truth you face a similar challenge when you’re hurrying somewhere and you find yourself on a crash-course towards an irritating person you really want to avoid. And though they’re not threatening to kill you, they may inadvertently bore you to death. Look again at the questions in the paragraph above – they still apply. If you’re in company now as you’re reading this, select someone nearby as a person you desperately want to avoid (you’ll need to invent a reason that relates to your social relationship with them). Keep your physical movement as minimal as possible and concentrate hard on what action you will take if they approach you.

Something which Stanislavski bravely asserted, and which I’ve hinted at in the scenarios described above, is that emotions are not things that you should ever plan in advance. Being able to act intense emotions on cue is sometimes seen as the mark of a great actor, but, in truth, while such acting can at best be very moving, at worst it can be an unwelcome party trick that simply detracts from the story of the play.

Still, it’s tempting (and common practice) to map out a character’s progress through a play by trying to pin down changing emotions. You think to yourself, ‘I’ll be angry at this point’ or ‘I was amused before but now my character’s getting upset’. Resist. If you build a performance from predetermined emotions, your acting will become generalised, predictable and unresponsive to the other actors. And you set yourself up to fail (‘damn, I didn’t cry on that bit AGAIN!’). Look at Hamlet. In his story he spends much of his time failing to act – he keeps discovering or inventing reasons why he should hold back. It’s tempting to label him as depressed, bitter – even suicidal. But play him that way and after two hours your audience will be egging him on to do it. Better instead to acknowledge Shakespeare’s talent for creating believable and sophisticated characters who act in response to their changing circumstances, and to work out what Hamlet is thinking. After all, who told the grieving Hamlet that his uncle murdered his father? A ghost, that’s who. I don’t know about you, but I’d need a bit more to go on before killing my uncle – especially if he’s making an effort to be nice to me. I’d need to do some soul-searching and some corroborative digging. For you, the actor, presented only with a script made up of dialogue, you will need to engage in some active imagining in order to breathe life into your character’s psychology.

If active imagining is so important for actors, how then can you develop your imagination? Simple: practice. Play ‘what if – ?’ games as you go about your daily business, and especially when you’re bored (when your mind is looking for a stimulus). Where should you start? Wherever you like. You could though do worse than revisiting some of the Exercises in earlier sections of this book and adding a powerful ‘what if – ?’ to each scenario.

Example: Natasha from Three Sisters

Read and rehearse this longer scene below from Act Three. For this scene to work fully for both actors and audience, there should initially be a strong sense of imminent threat (from fire, which has been sweeping through the town). The stress of this situation doubtless contributes to Natasha losing her temper so violently later in the scene and to other characters showing their true feelings too. As actors rehearsing the scene, you could start by asking, ‘What if, while we were running the scene, there was a genuine threat of fire outside the building?’ Try alternatives. Have you ever been in a place where there was a threat of natural disaster or terrorism? If so, try to recall the detail of that experience, what you wanted, what you actually did. Add it to the mix as you imagine the fire. If not, well, it is a magic if. Be as focused as possible – and imagine it.

[NATASHA comes in.]

NATASHA

They say we urgently need a committee to help the fire victims. What do you think? It’s an excellent idea. The poor need help, it’s the duty of the rich. Bobik and little Sophie are sleeping on as if nothing’s happened. There are so many people here, the place is full of them. There’s an outbreak of flu in the town. I’m so frightened the children will catch it.

OLGA [Not listening]

You can’t see the fire in this room, it’s quiet in here.

NATASHA

Yes … I suppose I’m a mess. [At the mirror] They say I’m putting on weight … it’s not true! It’s not. Masha’s fast asleep; the poor thing’s worn out. [Coldly, to ANFISA] How dare you sit in my presence! Get up! Go on, get out! [Exit ANFISA; a pause] I have no idea why you keep that old woman on.

OLGA [Confused]

I’m sorry, I don’t understand …

NATASHA

She’s no use here. She came from the countryside, she should go back to it … Spoiling her, I call it! I must have order in the house. We don’t want anyone useless here. [Strokes Olga’s cheek] You’re tired, poor thing! Our headmistress is tired! And when my little Sophie starts school I shall be so afraid of you.

OLGA

I shan’t be headmistress.

NATASHA

They’re going to appoint you, Olga. It’s settled.

OLGA

Then I’ll refuse the job. I can’t … I’m not strong enough … [Drinks water] You were so rude to nanny just now … I’m sorry. I can’t stand ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Foreword to the second edition by Sir Ben Kingsley

- Foreword to the first edition by Sir Alan Ayckbourn

- Introduction

- Section One: Skills for the Job

- Section Two: Planning to Act

- Section Three: The Body

- Section Four: The Voice

- Section Five: Speech

- Section Six: Inner Life

- Section Seven: Acting in Space

- Final Thoughts

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Imprint