![]()

| 1 | Historical Overview of Phonetics |

Chapter Overview

The Ancient World

The Middle Ages

Renaissance Europe

Seventeenth Century

Eighteenth Century

Nineteenth Century

This historical overview is in two parts. The first part identifies certain important milestones in the development of phonetics from earliest historical times up to the formation of the International Phonetic Association (IPA) in 1886. The second part reports on key advances in the discipline from that time to the present.

Phonetics from Ancient Times up to the IPA

Barry Heselwood

1 The Ancient World

1.1 Egypt

A hieroglyphic alphabet was in use for representing Ancient Egyptian consonants by the end of the fourth millennium BCE (Coulmas, 2003, pp. 173–5). Examples of rebus writing also date from this time (Baines, 2004, p. 163). Signs for vowels started to make sporadic appearances during the third millennium BCE (Gelb, 1963, p. 168). These developments require some analysis of pronunciation, albeit a pre-theoretical one. Rebus writing relies on recognition of the phonetic identity of homonyms but not on phonetic theory.

Acrophony may have played a significant role in the spread of writing in the ancient Near East (Gardiner, 1916). In acrophony a logogram becomes an alphabetic letter when it is used to represent the first sound of the word instead of the whole word, its signifying function shifting from lexis to phonology. For this to happen, there has to be recognition of the same sound in other word-forms.

The hieroglyphic alphabet, rebus writing and acrophony indicate that from the earliest known examples of written language deliberate pairing not only of words and written symbols but also of sounds and written symbols has been undertaken.

1.2 India

Probably the first systematic framework for the analysis of speech was developed in India in the early part of the first millennium BCE (Allen, 1953, p. 5; Varma, 1961, p. 4). Sanskrit consonants and vowels were classified according to articulatory criteria of place, manner and voicing in much the same way as the modern IPA, with the functions of active and passive articulators identified. Sounds were also quantified into mora-like units, consonants being half a unit, short vowels one and long vowels two (Varma, 1961, p. 89). They made discoveries of how voicing is generated in the larynx, theorized about syllabification and consonant-vowel dependencies, studied connected speech phenomena under the heading sandhi – a term still used in modern phonology – attended to the use of voice-pitch for tone and tried to account for the relationship of tone to quantity. Concerning tempo, they noted speech could be fast, medium or slow (ibid., p. 170).

When the work of the Indians became known in the West, it had a significant influence on phoneticians such as Alexander J. Ellis and Henry Sweet (Allen, 1953, p. 4).

1.3 Greece

The rudiments of a science of phonetics can be seen in the writings of Plato and Aristotle in the fourth century BCE. Plato, in his Theaetetus (202e–203c), mentions the differences between consonants and vowels and their combination into syllables. Allen (1953, p. 36) claims that Aristotle may have appreciated the role of the larynx in providing voicing for speech. However, when he says ‘we cannot use voice when breathing in or out, but only when holding the breath’ (De Anima, II.8.420b7), he displays crucial lack of understanding of the process.

The Stoic grammarians in the third to second centuries BCE distinguished between the signified and the signifier. The Aristotelian doctrine concerning writing that ‘written marks [are] symbols of spoken sounds’ (De Interpretatione, 16a3) meant that speech sounds were seen as the primary signifiers and became objects of study. They arranged consonants and vowels into nonsense sequences, venturing outside the constraints of Greek phonotactics (Robins, 1990, p. 28). Greek letters were thus being used less as a spelling system and more as a phonetic notation system with an embryonic body of phonetic theory behind it. Further development of Greek phonetic theory can be seen in the Téchnē Grammatiké attributed to Dionysius Thrax (ca. 170–ca. 90 BC). Sounds are cross-classified on the basis of shared manner features such as stop, continuant and aspiration. Thrax recognized in Greek three triads of aspirated-voiced-unaspirated plosives although he fell short of an accurate account of voicing as did all Greek and Roman commentators (Matthews, 1994, pp. 13–14).1 Terminology relating to manner of articulation was used with explicit phonetic definitions although, despite descriptions of labial, dental and velar stops (ibid., p. 13), no technical terms were coined by the Greeks for denoting places of articulation (Allen, 1981, pp. 119–21).

2 The Middle Ages

2.1 The Arab Grammarians

Although their descriptions of Arabic sounds tend to be brief and can sometimes be difficult to interpret, it is clear from the works of scholars such as Al-Khalīl (718–86 CE), Sībawayh (ca.750–796 CE), Ibn Jinnī (933–1002 CE) and Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) (980–1037 CE) that a fruitful phonetic tradition existed in the Middle East at this time.

Like the Greeks, the Arabs did not understand voicing but they went further than the Greeks in developing a framework and terminology for classifying sounds and arrived at insights such as Ibn Jinnī’s analogy between the vocal tract and a flute in the way sounds are made by forming closures at various points while forcing air through (Mehiri, 1973, p. 166).

Sībawayh developed a typology of connected speech phenomena, distinguishing different kinds and degrees of assimilation (Al-Nassir, 1993, pp. 56–80) very like modern discussions of gradient and categorical assimilation (e.g. Ellis & Hardcastle, 2002), and setting up a strength hierarchy in which greatest strength was assigned to sounds which most resist assimilation.

In the Arab treatises we encounter phonetic descriptions of dialectal differences, sociolinguistic variation and speech errors (Anwar, 1983). We also find a concern with methods of observation, data elicitation and the control of contextual variables of both a phonetic and a social nature (Alhawary, 2003). This empirical emphasis on observation under controlled conditions, together with many accurate descriptions of phonetic phenomena, marks the work of the medieval Arab phoneticians as a valuable contribution in the history of the discipline (see Heselwood & Hassan, forthcoming).

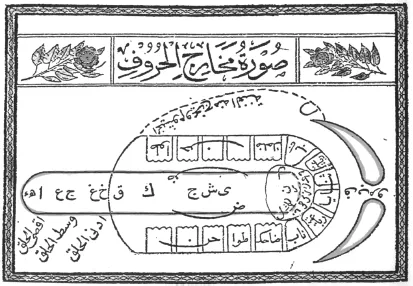

Figure 1.1 Vocal tract diagram entitled S ?ūrat makhārij al-h?urūf ‘Picture of the exits of the letters’ from Miftāh? al-‘Ulūm ‘The Key to the Sciences’ by Al-Sakkāki. Dotted line indicates the nasal passage with a nostril above the lip.

The Arab tradition produced what is probably the earliest diagram of the vocal tract. It appeared in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century CE and is reproduced in Figure 1.1 (from Bakalla, 1982, p. 87). Arabic letters are arranged at the places of articulation of the corresponding sounds, thus giving the letters the function of phonetic symbols.

2.2 Europe

Very little study of phonetics went on in Europe in the Middle Ages (Robins, 1990, p. 87). Observations of how Latin sounds were influenced by local vernaculars were couched mostly in impressionistic terms and were largely confined to remarking on the effects of context on sound quality. For example, lenition processes were noted, as was a tendency for voiceless fricatives to become voiced intervocalically (see the accounts of various treatises of the time in Vineis & Maierú, 1994, pp. 190–7).

The anonymous First Grammatical Treatise, from twelfth-century Iceland, has been cited as representing the most advanced phonetic analysis of the medieval period in Europe (Robins, 1990, p. 82; Vineis & Maierú, 1994, p. 187). It offers a comprehensive componential analysis of vowel qualities in Old Norse, distinguishes nasalized and non-nasalized vowels, short and long vowels, degrees of vowel openness, adduces minimal pairs to prove the existence of these distinctions and provides new letters for them by diacritical modifications to the five Latin vowel letters (Haugen, 1972, pp. 15–19, 34–41). However, there is no mention of lip-shape in vowels and, apart from distinguishing singletons and geminates, there is no attempt at a phonetic classification of consonants.

Common to phonetics in all periods before the Renaissance was a focus on the pronunciation of a particular language – Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Arabic, Norse – with some limited attention to dialectal variants. The concept of a ‘general phonetics’ had yet to emerge.

3 Renaissance Europe

The issue of whether to write Romance vernaculars so that spellings reflected vernacular pronunciation or Latin etymology became important in Renaissance Europe, the debate often dividing strongly along religious and ideological lines (Tavoni, 1998, pp. 18–29). The Calvinist Louis Meigret (ca.1500–1558) viewed spellings which were not true to pronunciation as ‘superstitions’ and developed his own phonetically reformed orthography for French. Concern with spelling reform and orthographic invention, in eastern as well as western Europe (Gandolfo, 1998, pp. 111–14), raised practical and theoretical questions about the representation of speech sounds.

The late fifteenth century also saw diachronic and comparative examination of classical and vernacular languages, treating them as linguistic equals subject to the same phonetic laws (Tavoni, 1998, pp. 46–7), but we have to wait another century for Jacob Madsen’s De literis libri duo (1586) before we have the first known publication taking an explicitly general phonetics perspective (Kemp, 2006, p. 473). The vocal tract and the sounds it can produce, rather than the pronunciations of particular languages, increasingly become objects of study in subsequent works (ibid., pp. 476–7).

Western general phonetic theory made significant strides in England through the work of Sir Thomas Smith (1513–77), John Hart (ca.1500–1574) and other sixteenth- and seventeenth-century scholars. They are the early figures in what has, since Sweet’s coining of the phrase, become known as ‘the English school of phonetics’ (Firth, 1957).

Both Hart and Smith augmented the Latin alphabet with some letters of their own devising. While Smith employed experimental methods of phonetic self-observation (e.g. Smith, 1568, pp. 34–5), he displayed an absence of adequate analytic terms in his ostensive definitions of sounds. His achievement was to set out a system of phoneme-grapheme correspondences for English (Cecioni, 1980, p. 91). Hart makes the greater contribution to phonetic theory by describing speech-sound production in some detail and grouping sounds together on the basis of shared phonetic parameters (e.g. Hart, 1569, pp. 41–2). Danielsson (1955, p. 220) credits him as the first European to note anticipatory assimilation across word boundaries in connected speech. We must remember, however, that insofar as Hart developed a phonetic theory it was to serve as a justification for spelling reform.

4 Seventeenth Century

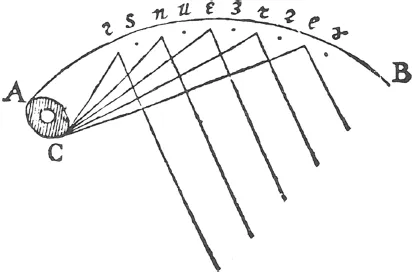

Robert Robinson’s 1617 The Art of Pronuntiation contains perhaps the earliest example of a vowel chart (see Figure 1.2). It shows the position of the high point of the tongue in relation to the palate for five vowel qualities with symbols to represent short and long versions. He devised a complete set of new symbols instead of adapting or adding to alphabetic letters, treated voicing as a prosody and classified sounds according to an original scheme in which the vocal tract is divided into ‘outward’, ‘middle’ and ‘inward’ regions with four manner distinctions corresponding to plosive, nasal, fricative and approximant (Dobson, 1957, pp. 23–4). Although the assigning of sounds to the regions is sometimes counter to modern phonetics, and his symbols may be ‘easier to forget than to learn’ (ibid., p. xi), Robinson’s work shows an advance towards a phonetics free from the letter-based thinking of the past, with a marriage of taxonomy and notation of the kind that underpins the modern IPA system.

Figure 1.2 Robinson’s 1617 vowel chart. A = glottis, B = front of palate, C = tongue root.

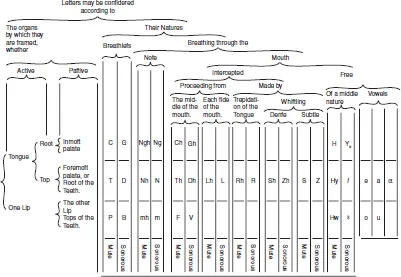

John Wallis (1616–1703) in his Tractatus de loquela of 1653 presents tables arranged so that sounds appear as the products of intersecting categories (see Kemp, 1972, pp. 196–7) as they do on IPA charts (IPA, 1999, p. 159). The significance of a chart with intersecting dimensions is that it becomes a model of phonetic space rather than, in the case of Robinson’s chart, a model of the vocal tract. It is therefore more abstract and the dimensions can take on the status of autonomous components.

The teenage Isaac Newton (1643–1727) set out a classification of consonants and vowels and devised an original set of symbols to represent them systematically. He also reported an experiment in which ‘The filling of a very deepe flaggon wth a constant streame of beere or water sounds ye vowells in this order w, u, ω, o, a, e, i, y’ (Elliott, 1954, p. 12).

Figure 1.3 Wilkins’ chart with consonants and vowels arranged in a hierarchy of binary distinctions. Reproduced with the permission of the Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library.

John Wilkins (1614–72), Bishop of Chester, was influential in the movement to establish a set of sounds for the pronunciation of a universal language, a preoccupation of the time (Robins, 1990, pp. 126–30). Viewed as a model of phonetic space, Wilkins’ cross-classificatory chart (see Figure 1.3) is more sophisticated than Wallis’s. It is structured by a hierarchy of binary distinctions, incorporates both vowels and consonants, and shows a more detailed appreciation of articulatory structures and processes. An innovative feature of Wilkins’ work is his design of an ‘organic alphabet’ of symbols as iconic representations of articulatory-aerodynamic properties of sounds (Wilkins, 1668, p. 378; see also Allbright, 1958, pp. 8–10). Organic symbols explicitly identify sounds as objects of study independently of any writing system and therefore imply the possibility of phonetics as a language-independent discipline drawing on the disciplines of anatomy and physiology. Wilkins also designed letters systematically based on the component features of sounds (Wilkins, 1668, p. 376), similar to Newton’s and to the universal alphabet designed by Francis...