- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Offers an easily accessible specific methodology for describing the nuances of spoken and written texts, of any length, in meaning and manageable ways

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Communication Linguistics

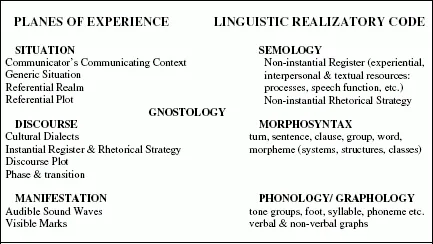

Communication Linguistics is the theoretical orientation of the descriptive framework and methodology known as phasal analysis. It was introduced in the mid-1980s by Michael Gregory and Karen Malcolm (Gregory, 1985; Malcolm, 1985a) as a development of Michael Halliday’s systemic model (1978, 1994), and as influenced by Ilah Fleming’s stratificational communicative model (1988) and Ken Pike’s tagmemics (1982). In Communication Linguistics, language is considered from both a social and cognitive perspective. Socially, language is an intentionally communicative behaviour that enables language users to exchange meanings, negotiate status, maintain cultural values and beliefs in a particular situation and culture. Cognitively, language involves both what the encoder knows and intends and what the decoder knows and interprets. To capture both the social and cognitive aspects of communication, Communication Linguistics differentiates between planes of experience and language’s realizatory code (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Malcolm (2005 Linguistica; cf. Malcolm, 1985a, p.137).

Before the framework of Communication Linguistics is discussed, a few more basic concepts will be introduced.

Communicative event

A communicative event is an event in a situation and culture in which language (spoken or written) and / or visual images are manifested by someone (the encoder) to communicate something (the manifested message or discourse) to someone else (the decoder).

Encoder and decoder

The terms encoder and decoder refer to the real-life interactive participants in the situation that produce and receive images. Encoder refers to the writer, speaker or visual artist who chooses, consciously or unconsciously, what language and / or visual alternatives to communicate. Her choices are based on both her intentions to communicate a particular message and her familiarity with the various linguistic and visual systems of options that are available to her in the particular situation and culture that will enable her to fulfil her communicative intentions. A decoder is the person who reads, hears or sees the message and who interprets it through her own experience and knowledge of the communicative options available in the situation and culture. Represented participants are those people or things represented in the discourse and / or in the visual images included in the text: they may be fictional or representations of real people, as in photographs or written memoirs.

Message, discourse and text

Message refers to the meaning that is exchanged in the communicative event between the encoder and decoder. The message is manifested as visible marks on a page or in audible sound waves. The word discourse refers to the product of the intentionally communicative event: the message that has been manifested in the situation. The word discourse is used in contrast to the word text. Text refers to the written record of the verbal (spoken or written), visual or multimodal discourse. A text generally forms a unified whole that exhibits an internal connectedness or coherence. If the discourse were written, the text would be equivalent to the same written document as the discourse. However, if the original discourse were spoken, manifested in audible sound waves, the text would be the written transcription of a recording made of the spoken discourse. The distinction between discourse and text, then, is particularly important when analysing spoken discourse, where the written text is different from the original discourse and is subject to possible errors and omissions made by the transcriber when transcribing the communicative event. In this textbook, the word text is used more than discourse because, for the purpose of analysis, all discourses, whether originally manifested in speech or writing, are presented as written / transcribed texts.

Marked and unmarked

The notion of marked language versus unmarked is useful to analysts who compare one text to another. Very simply, unmarked tests are typical, predictable and often somewhat stereotypical, while marked texts are unusual, unpredictable, differing from language users’ expectations. The value of using a cline between highly marked texts and very typical unmarked texts will become much clearer as you follow the analyses of marked and unmarked examples of texts included in this book.

To the analyst, unpredictable marked examples of discourse may seem more interesting than the many texts which are unmarked and culturally predictable. Marked texts are more likely to exemplify a new range of stylistic possibilities which enable the analyst to make new discoveries about the linguistic choices used either to encode complex and indirect intentions or to decode subtle readings and interpretations. However, much of language is necessarily unmarked and predictable in order to facilitate clear and easy interpretation. Whether focused on marked or unmarked texts, linguistic analysis is descriptive rather than prescriptive or evaluative: one text is not valued more than another.

Planes of experience

The planes of experience of Communication Linguistics describe the actual communicative event as a dynamic process that happens in a ‘real’ instance of time and space. The three planes of experience relevant to the communicative event are situation, discourse and manifestation. The central discourse plane represents the communicative event itself in which the language / discourse is manifested in its situation. You might think of it as the product of communication. More specifically, the discourse plane is defined as the linguistic realization of what the encoder has selected as communicatively relevant to the decoding receiver. It is the manifested message which is simultaneously an instance of, and evidence for, our linguistic and cultural knowledge. The plane of experience entitled manifestation refers to the intentionally communicative speech sounds, visible marks on a page, gestures and / or facial expressions that are manifested in the communicative event as the discourse. You might think of it as the process of communication. The upper most plane, situation, describes the contextual features of the situation and culture that are relevant to the communicative event described in the manifested discourse. You might think of it as the context of communication.

Situation

The culture and situation relevant to the communicative event are described using four variables: referential realm, referential plot, communicator’s communicating context and generic situation. In Communication Linguistics we define referential realm as the real or imagined persons, things, events and interactional intents and attitudes that are available in the world (situation and culture) to be encoded in the message. The term was borrowed from Ilah Fleming. ‘[Referential realm] involves anything a communicator wishes to talk about in his message’, no matter whether it is factual, hypothetical, mythical, concrete or abstract (Fleming, 1988, p. 298). More simply, referential realm refers to everything and anything that could be talked about in a situation and culture. From the referential realm of possibilities the encoder selects her referential plot. The referential plot refers to the ‘real’ sequence of persons, things, events, intents and attitudes and so on that are actually selected from the referential realm of possibilities to be included in the message of the communicative event (Gregory, 1985, p. 203). More simply, referential plot refers to the specific sequence of the events that the encoder chooses to communicate.

The Communicator’s Communicating Context (CCC) describes the comparatively permanent cultural context of the interlocutors’ situation in terms of their temporal, geographical, social and individual provenance. Throughout the textbook, the word ‘culture’ refers, more generally, to these aspects of the CCC. Generic Situation (GS) describes the more impermanent and immediate relationships that characterize their communicative situation. The user’s and receiver’s relationships to the experience is called the interlocutors’ representational relationship. Their relationship to each other is called the interactional relationship. Their relationship to the medium of transmission of the discourse, be it spoken or written, is the medium relationship, and to the purpose of the discourse is their functional relationship. These various relationships are referred to as field, personal tenor, mode and functional tenor, respectively, by systemic linguists. In the textbook, ‘situation’ is used to describe, more generally, the relationships of the GS.

The interrelationships between culture, situation and language have been studied for much of the twentieth century, particularly by those involved in anthropologically oriented research. Both Boas, in his research on the language of Baffinland, and Malinowski, in his work on the discourse of Trobriand Islanders, realized that discourse could not be translated without an understanding of cultural and situational contexts (cf. Dinneen, 1978, pp. 213, 300). These ideas were further developed by Firth, who talked about the importance of the context of culture and context of situation in describing the communicative event (ibid.). In the 1970s Halliday and other systemicists developed these ideas more fully by relating the systems of language to the functions of language and to the field, mode and tenor in situation (1973, p. 99). Insights into context of culture led to the CCC of Communication Linguistics; whereas the development of context of situation led to GS.

Communicator’s Communicating Context

The CCC captures and classifies those features of the culture that are relevant to any communication. If you step into a new country, travel back in time, or even walk across town to where people from a different socio-economic or ethnic group live and communicate, you become acutely aware of the cultural specificity of language when familiar points of reference disappear, and you find yourself in unfamiliar terrain, perhaps even unable to communicate (cf. ‘communicative competence’ Bonvillain, 2003, Chapter 10). In different geographical provenances only a few miles apart, Northern Germany and Southern Denmark, for example, inhabitants use an entirely different language to communicate. Trying to interpret the meaning of Early Modern English Shakespeare, not to mention the Old English of several centuries earlier, makes the difficulties of interpreting the language and culture of a different temporal provenance very clear. Languages change over time, from place to place, and even from group to group. Age, gender, ethnicity, social class, level of education, economic status, religious affiliation and political ideology are some of the factors that determine an interlocutor’s social provenance, which also affects communicative choices. Each configuration of temporal, geographical and social provenance convey different belief systems, different assumptions, different customs and different values, each with its repository of communicative resources available to language encoders and decoders alike. When an encoder from one social group communicates to a decoder from a different social group, even man to woman, grandparent to grandchild, communication may prove challenging.

Many linguists over the past century have noticed that language and culture interrelate in a mutual dialectic (Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, cf. Bonvillain, p. 49). The beliefs and values held by the people of a particular culture determine the breadth and variety of linguistic resources that are created or acquired to communicate them. While, at the same time, the range of linguistic possibilities constrains the way language users are willing, and able, to think and communicate.

Cultural dialects, in the Discourse Plane, are the linguistic reflection of the temporal, geographical and social provenances of the CCC in the Situation Plane. There is also a fourth dimension of the CCC: individual provenance. Have you ever noticed that one of your friends speaks in a unique style? Or, at some point in your life, have you deliberately cultivated a personal style or voice, that transcends, or even challenges, the temporal, geographical and social norms of your cultural dialect? In your writing and speaking, your communication will inevitably be affected by the range of linguistic resources that reflect your beliefs, attitudes and values. In other words, your individual provenance is bound to affect your personal dialect as well as the time, place and society in which you live.

Generic Situation

Just as the variety in our cultural provenance influences the communicative resources we bring to each communicative event, so do the relationships that capture the different aspects of the communicative situation. In the 1960s, systemicists coined the words field, mode and tenor to describe these relationships. Generally speaking, field refers to the relationship between communicators and the experience they are representing in their discourse. Mode refers to the relationship between the interlocutors and their chosen medium of transmission in the communicative event. Personal tenor refers to the relationship between the encoder and decoder involved in the communicative interaction. And functional tenor refers to the purposeful relationship between the interactants involved in the communicative event (cf. Gregory and Carroll, 1978; Halliday, 1978).

Field is the aspect of the situation that describes the focus of the activity or experience represented in the message. Eggins writes that field can be glossed as the ‘topic’ of the situation that varies in terms of technicality (1994, pp. 67–74). In everyday situations, common knowledge is sufficient background for communication. Everyday language uses ordinary terms that most people can understand to share experiences. However, in technically specialized situations, where there is an assumed knowledge of, and expertise in, a specific activity, there is a greater likelihood of a technical jargon, understood by ‘insiders’ only, people who share the same technical expertise. Acronyms like DNS, VPN and DHCP; abbreviated syntax like ping it, and technical action processes like virtualize a PC are signals of technical co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Texts

- Examples of Analysis

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Communication Linguistics

- 2. Graphology

- 3. Phonology

- 4. Lexis

- 5. Syntax

- 6. Semology

- 7. Rhetorical Strategies

- 8. Phasal Analysis

- Works Cited

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Phasal Analysis by Karen Malcolm in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistic Semantics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.