![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Place for me?

My home, my place

Few authors have captured the importance of place in our psyche as successfully as Irish playwright Brian Friel has done. Friel’s work illustrates the centrality of place for people of diasporas, who leave their homelands for new opportunities, and for communities who seek redress for past injuries. Thoughts of place and home can trigger feelings of deep longing as well as a sense of belonging and hope. In Friel’s play Dancing at Lughnasa, Michael looks back to the summer of his youth in which his mother and her sisters danced with abandon and joy.

When I cast my mind back to that summer of 1936, different kinds of memories offer themselves to me. We got our first wireless set that summer – well, a sort of a set; and it obsessed us. And because it arrived as August was about to begin, my Aunt Maggie – she was the joker of the family – she suggested we give it a name. She wanted to call it Lugh after the old Celtic God of the Harvest. Because in the old days August the First was La Lughnasa, the feast day of the pagan god, Lugh; and the days and weeks of harvesting that followed were called the Festival of Lughnasa. But Aunt Kate – she was a national schoolteacher and a very proper woman – she said it would be sinful to christen an inanimate object with any kind of name, not to talk of a pagan god. So we just called it Marconi because that was the name emblazoned on the set.

. . . I remember my first delight, indeed my awe, at the sheer magic of that radio. . . . I remember the kitchen throbbing with the beat of Irish dance music beamed to us all the way from Dublin, and my mother and her sisters suddenly catching hands and dancing a spontaneous step-dance and laughing – screaming! – like excited schoolgirls.

Friel was born in Omagh, County Tyrone (Boltwood 2007). In Dancing at Lughnasa, Friel captures the poignancy of a community whose hopes and dreams are slowly eroded, as social and economic forces push the community gradually, inexorably, into decline. The only way out is to leave Ireland. By the end of the play, Michael’s family has become divided: two of the sisters have departed to London, never to be seen again. Michael has witnessed the last occasion on which the four sisters would dance together.

In The Home Place, Friel grapples with the notion of identity. The context for the play is the resurgence of the Home Rule for Ireland movement in the summer of 1878. Landowner Christopher Gore, a main character in the play, has to answer the question: Whose side are you on? The choice for Gore is between the country of his birth (England) and the country in which he now owns land and property (Ireland). For many immigrants and refugees today, the question Whose side are you on? Can be a difficult one, particularly when there is conflict. It forces them to reconcile feelings about the land of their birth with those of their adopted homes.

‘Home’ is a fragile concept, idealized by those who have become part of the world’s diasporas. I live in London but remain a Mancunian. Yet, connections to birthplace and home ties have loosened in many Western contemporary societies. Change of residences has become more common. People move around their neighbourhood, their towns, their cities, within countries or to different countries. And yet, the place where we are from is essential to our identity and to the stories we tell of our lives.

In The Freedom of the City, Friel tackles issues of place, power and belonging. The play is set in Derry, Northern Ireland, in 1973, in the aftermath of the Roman Catholic Civil Rights meeting which, following the death of 13 protestors, came to be known as Bloody Sunday. It centres on three protesters who accidentally find themselves in the mayor’s parlour in the Guildhall: an action that is interpreted as an ‘occupation’ and which leads to their deaths. People can find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Space and place

The scramble for space

The struggle for place begins first with a struggle for space. Mamphela Ramphele captures this battle for space in her powerful book on the lives of the migrant labour hostel dwellers of Cape Town, South Africa. Its evocative title, ‘A Bed Called Home’, reminds us of the power of the concepts of space and place. The hostel dwellers in a spartan and crowded building in South Africa have taken their only personal space (their bed) and turned that space into their home: an act that expresses the need we all have to find some space with which to identify. Ramphele (1993) charts the many dimensions of space, arguing that the capacity of the hostel dwellers to act is constrained by their limited access to political, social, economic, intellectual and psychological space. In this analysis of the multidimensional nature of space, Ramphele suggests that the space individuals inhabit has a profound impact on their sense of self.

To a large extent inhabited space has a major impact on the self-image of individuals and their perception of their place in society. For hostel dwellers, interesting questions arise about the impact of the constant assault on their dignity in the work environment, where they do menial jobs, and in their accommodation, with its squalor and lack of privacy.

(Ramphele 1993, p. 7)

Inhabited space shapes expectations and aspirations, and views about place in society. Political decisions shape access to physical space – in terms of both quality and quantity. Ramphele demonstrates the ways in which the many different aspects of space have a profound effect on individuals, in terms of intellectual expectations, as well as their assumptions about the norms of behaviour and relationships. Reflecting on the experiences of the labour hostel dwellers, she concludes that the ‘inhabitated space’ that individuals find themselves in provides them with cues that encourage them to expand or contract their expectations.

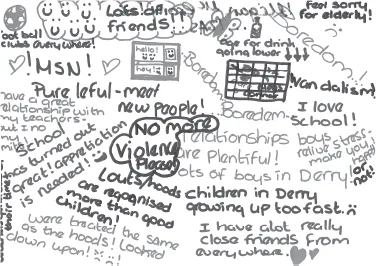

Notions of space can be translated into the world of the school and the world that young people inhabit around their school. In an interesting book on young people in our global cities, Jo-Anne Dillabough and Jacqueline Kennelly (2010) put forward three concepts to help us think about space and locality for young people. I have provided examples of young people’s drawings from the project Leadership on the Front-line (which is discussed more fully in Chapter 3) which seem to exemplify each of the concepts. The young people interviewed as part of the project were asked to depict their daily lives, illustrating the good and bad features.

The first of these concepts of space for young people is the notion of particular spaces, such as the corridors within a school, as fluid arenas in which relationships are constantly being reshaped. The school corridor is often an area within the school that is free from teacher-based authority. In this vacuum, relationships between students can emerge in powerful ways, both positively or negatively – through, for example, bullying or racism.

In Illustration 1.1, a student from an inner-city school in London has drawn the corridor space. It is a lonely and empty area that suddenly can become a packed, bustling thoroughfare. The arrows indicate which direction to walk, and the identical doors presage the moment when unknown groups of students will pour out of them into the corridor.

The second concept of space refers to particular localities and to the knowledge that shapes young people’s views about who they are in relation to those localities. The everyday activities, experiences and cultural practices in their neighbourhood influence how young people see themselves as being valued in the wider world. I have included many examples of this in the three locality studies later in the book. To illustrate the point here I have included Illustration 1.2 a drawing made by a young child from Manchester. It depicts his sadness about some of the experiences he encounters in his local area. What he faces on the street is very different from what he experiences at school. His text reads:

ILLUSTRATION 1.1

ILLUSTRATION 1.2

I heyt gun shots. (I hate gun shots.)

I heyt wen the sun gets in my ice. (I hate it when the sun gets in my eyes.)

The third concept is to do with space and new and emerging forms of social conflict. It picks up on the resentment that some young people experience when they are caught up in events in which they have little or no control, or when they are blamed for the actions of others. Dissent can manifest itself in a number of ways, such as particular forms of popular culture, such as rap. In illustration 1.3, which is from Derry/Londonderry, the resentment is palpable. The ‘louts’ get all the attention. Part of the text in the illustration reads:

Louts/hoods are recognised more than the good children . . . We’re treated the same as the hoods! Looked down upon . . .

ILLUSTRATION 1.3

As the three images demonstrate, young people can struggle to come to terms with the space around them. The space may be alien, unsafe, threatening. The space they inhabit in their locality may not feel like their place because it is a place divided.

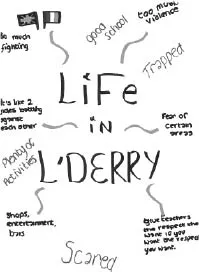

The struggle for place

The struggle for place can be ongoing and relentless. In the introduction, I gave the Derry/Londonderry example to illustrate the significance of the question Where are you from? and the answer to that question. In the illustration 1.4, again from the project Leadership on the Frontline, Mairi illustrates the contrasts in her life in ‘L’Derry’: a good school and plenty of activities and entertainment but two sides battling against each. The illustration captures her experience of the dividing line which still characterizes the daily encounters and experiences of many. In her experience, it is a place divided. Some people live in fear. She feels trapped and she is scared.

ILLUSTRATION 1.4

One of the school principals from Northern Ireland involved in Leadership on the Front-line commented on its implications for young people. He voiced his heart-felt concerns for young people on both sides of the sectarian divide thus:

Our schools are on either side of the community divide but the problems are the same. The kids are fearful, the lawlessness of the town, certain areas they don’t feel safe – these are the issues that are coming out for us. Dealing with that is the brutal truth, and to do something constructive about that. I’m quite at a loss to think about it.

While young people in Northern Ireland may have a clear sense of their identity, in terms of their roots, their beliefs their families’ political allegiances, in a divided country, the notion of place is fractured and limiting. Place is a foundation stone for social meaning and social interactions. It connects with many stories and many lives. The history of place echoes through the years. In the play Translations, Brian Friel highlights the ways in which linguistic, cultural and generational factors influence our experience of place. The play is set in a quiet community in the Ireland of 1833 – just before the potato famine. It is performed in Gaelic and English and charts the progress of an English military expedition whose task it is to map the country1 and convert all Gaelic place names into English. The star-crossed lovers are an Irish woman who speaks no English and an English soldier who speaks no Irish. Although the villagers have little experience of the outside world, tales of Greek goddesses are commonplace, and Latin and Greek spoken.

The play has become one of the most widely translated and produced plays of the post-World War II era, testimony to the significance of place and identity in our fast moving global world (Wikipedia 2012). The play’s power lies in its capacity to communicate the importance for all of finding a home and people to share our lives with.

In Translations, the voices of the outsider are heard in different guises. The fragile sense of belonging hangs in the balance. The outsider has to learn life afresh. The outsider may be the person who finds that their homeland is no longer theirs, as is the case for this Irish character in Translations who says:

We must learn those new names . . . We must learn where we live.

We must learn to make them our own.

The outsider may be the person who seeks to settle in a new country but fears they will never quite belong. These fears are echoed in the words of the English soldier in Translations who dreams of the possibility and impossibili...