![]()

1

Painting as an Art: Wollheim and the Subjective Dimension

Introduction

There are extensive discussions of visual art throughout Wollheim’s work. However, his book Painting as an Art offers arguments especially relevant to the present work.1 The book is addressed to a broad rather than specifically philosophical audience, but has, nevertheless, formidable conceptual substance – both in its general theory of painting and its searching phenomenology of spectatorial experience. Indeed, as well as offering the most comprehensive analytic account of painting as an art, Wollheim also assigns decisive roles to intention and expression – two of recent analytic aesthetics’ most favoured concepts.2 He is committed to an ‘internalist’ conception of painting’s artistic status. This centres on the relation between the activity from which paintings issue, the way it is practiced and the background knowledge (or ‘cognitive stock’) whereby the spectator recognizes a particular painting to be a work of art.

Part one of this chapter addresses painting as an activity, and the key concepts of ‘Ur-painting’ and ‘style’ through which Wollheim clarifies it. Part two considers his account of the spectator’s understanding, and, in particular, the decisive relation between expressive perception and expression through painting.

In Parts three and four, sustained critical appraisals of Wollheim’s key concepts are offered. The former focuses on difficulties accruing to his theory of style, and the latter on the problematics of his understanding of the relation between art and expression. In Conclusion, I consider and refute two more general defences of Wolheim’s position, and go on to identify the deep-seated problems at the root of his difficulties.

Part one

The starting point for Wollheim’s philosophy of painting is a basic theory of action. For him, intentional acts are intentional relative to a description. Of course, an individual act can be the subject of many descriptions; but they do not all pick out its intentional core. Wollheim offers, accordingly, the following refinement.

Now since painting is an intentional activity, the ways in which it is practised will embody the particular descriptions – or ‘thoughts’ under which it is intentional. Most important here are the ways in which those intentions are formed and changed on the basis of new guiding descriptions. In order to understand these intention-guiding descriptions, Wollheim introduces the notion of ‘Ur-painting’ – a thought model that considers painting in terms of the activity’s most basic characteristics. He presents the model in six descriptive steps. Each of these involves a ‘thematization’, that is, a description of some aspect of painting which then becomes a thought that guides the painter’s intentions and practice. These thematizations are, according to Wollheim, necessary to painting practised as an art.

1.The model starts with an agent placed next to a support, who places marks on the support using a charged instrument. This is the most basic description under which painting as an act is intentional.

2.As marks are placed on the support, one part of the surface will become obscured by them, leaving a contrasting (and decreasing) unmarked area. The agent may then become attentive to this relation, and, in placing marks on the surface, be influenced in what he or she does by the contrast between the marked area and the unmarked zone that borders it.

3.The painter can become attentive to the fact that each time a mark is placed on the support, it lies at a certain distance from each of the edges. This description can then guide the painter’s action, in addition to the factors already described.

4.The painter notices that there is a certain coalescence of placed marks into wholes or units wherein groups of them are seen as one. If the painter’s subsequent placing of marks is guided by this forming of groups of marks into unities, then, according to Wollheim ‘He has organized the motif.’4

5.Though constructing motifs intentionally, the painter notices a decisive new factor. For, in beholding them, a special kind of perceptual experience arises. As well as seeing the marks distributed on the surface per se, the painter comes, at the same time, to experience the marks as presenting something in front of, or standing out ahead of, something else. This experience of ‘seeing-in’ – orientated around the ‘twofoldness’ – ‘of seeing the marked surface, and of seeing something in the surface’5 is, according to Wollheim, not altogether new to the painter. He or she has seen things ‘in’ clouds, or stained walls and the like. However, the strategy of making things appear in front of other things can now guide the way the painter marks the surface. He or she forms ‘motifs’, and, in doing so, ‘thematizes the image.’6

6.The final and overriding thematization is that painting involves the realization of some purpose. It is only in relation to purpose that the various intentional aspects Wollheim has described can be coordinated as a unified activity, and the mere material of mark and support become the medium of a practice. In the broadest terms, the end in question here consists of the surface being endowed with content or meaning ‘and meaning may in turn be glossed as that which we understand when we understand a painting: when we understand not some fact about the painting, but the painting itself.’7 In effect, this means that we are concerned with how the painting realizes the artist’s intentions, rather than facts concerning its practical/informational function.

Now Wollheim himself rather underestimates the significance of Ur-painting – suggesting that it might be regarded as something analogous to those models of a ‘state of nature’ popular in late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth-century political theory. However, while these models are postulates devised for methodological use, Ur-painting is actually much more than this. In order to see why, it is important to disregard Wollheim’s presentation of it as a kind of narrative of discovery, and treat it instead as a characterization of compositional aspects which are basic to making a painting. Seen in this light, Wollheim’s model embodies a kind of phenomenological reduction that isolates the essence of painting as an activity.

Painting, of course, serves all sorts of communicative functions, and is done with many different materials. However, if it is painting rather than some other visual practice, then all the factors that Wollheim describes are implicated in it to some degree. Whether it is oil, acrylic or watercolour, or drawing pure and simple, to make images using these media or idioms – however simple – demands attention to all the thematics that Wollheim describes.8

There is scope for a much deeper phenomenological development of Ur-painting. However, for present purposes, the more pressing concern is to show how the initial transition from painting, to painting considered as an art might be made. For Wollheim, the answer is found in the idea of that distinctively pictorial meaning which constitutes the last-mentioned thematizing factor. All paintings have it, but with many examples, we are interested in the specific use that the meaning is created for, rather than the content-creating act through which this use-value is made available.

Painting as an art directs us towards the thematizing factors that are involved in this content-creating act, as such, and, more specifically, their relation to the individual painter’s intentions. In this respect, Wollheim centres pictorial meaning of the artistic kind on how it presents, (a) the artist’s mental state, (b) the way this causes him or her to mark the surface and (c) the mental state that results from the sensitive informed spectator’s perception of the marked surface. One might put it like this. Functional painting refers us to practically significant meanings determined by the relation between the work and specific ‘external’ cultural contexts; artistic painting refers us to the painter’s self-presentation within the internal resources of the work itself, as the locus of meaning.

This self-presentation converges on a specific factor. As Wollheim puts it,

It seems odd to use the term ‘deletion’ here, in that the suppression of previously thematized features is surely most often achieved through accentuating new themata in a way that erases or diminishes emphases previously placed. However, whatever the case, Wollheim suggests that the most likely reason for deletion is the artist’s sense that it is no longer significant in terms of the artist’s own practice and that of his or her contemporaries and predecessors. This means that the function of deletion is to ensure continuing meaningfulness. Tradition or a sense of the past acts as a starting point for the present, both constraining and encouraging the painter to exceed these constraints through new departures.

Now, it should be emphasized that the succession of thematizing emphases is not a continuing or a continuous process, and neither does it operate at a uniform pace throughout the artist’s career. The artist, as it were, ‘banks’ his or her advances. It is in relation to this that Wollheim introduces the focal concept of ‘style’. He notes the existence of general style – which encompasses universal factors (e.g. geometric, painterly or classicist tendencies); or historical periods (such as neoclassicism, or International Gothic) or, indeed, ‘schools’ (e.g. Giottesque, Nazarene, the Norwich School, etc.). However, for Wollheim, these general notions of style are mere shorthand for sets of characteristics. What is taken as constitutive of them changes on the basis of shifting perspectives in art history.

In contrast to this,

This is the major point upon which all Wollheim’s arguments ultimately converge. For him, there is a conceptual link between having an individual style, and a painter being an artist. As I understand him, there are, again, six – rather complex aspects – to individual style.

1.The characteristics associated with it do not alter, though art historians may well struggle to formulate these, and disagree with one another, in relation to understanding the specific artist.

2.Individual style is not (as in the general senses of the term) a mere shorthand for characteristics associated with it. Indeed, Wollheim emphasizes that ‘the style itself is distinct from the characteristics associated with it, and it is it that causes them to be as they are. Individual style is in the artist who has it, [indeed] . . . style has psychological reality.’11 Style, in other words, is a ‘psychological’ state that entails the artist’s absolute ownership of those characteristics that express it.

3.Individual style has explanatory power in a way that more general notions do not. As Wollheim puts it, ‘If general style dropped out of our thinking, we should lose a tool of classification. If individual style dropped out of our thinking, we should lose a form of explanation – as well as losing sight of a piece of reality.’12 Individual style has this significance because (a) it allows us to explain why a particular painting by an artist who has a style looks the way that it does; (b) it can explain why two works by him or her – painted in reasonably close temporal proximity – look the way they do and (c) it can allow us to explain the dissimilarities between artists who have different styles.

4.Individual style has a further, very complex diachronic historical aspect, whose bare exposition requires considerable detail. We are told, for example, that one painting can be stylistic, while another painting is not; or that the peculiarities of a specific painting can be explained by the fact of it being ‘non-stylistic’.

The term ‘non-stylistic’ is of some importance, and Wollheim analyses it as follows. Its first and most obvious manifestation is in terms of the ‘pre-stylistic’. This consists of the phase before a style is actually formed (which entails as its corollary that it is only with an artist whose style is formed late that it is instructive to recognize some of his or her work as pre-stylistic).

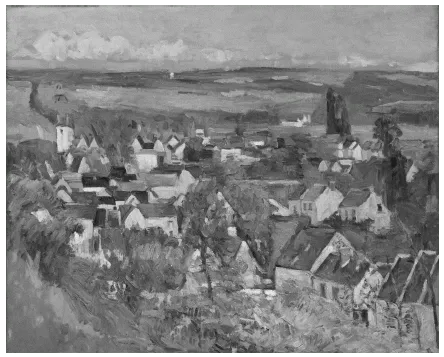

In respect of this notion, Wollheim compares and contrasts two paintings by Cezanne – Auvers, Panoramic View (c. 1874) and Le ChateauMedan (c. 1880) (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

Wollheim suggests that Cezanne’s work even up to the mid-1870s can be regarded as pre-stylistic, and that this is shown in the difference between these two works. The former is on the way to what is achieved in the latter. Ironically, it is a strongly and firmly realized work, whereas the later painting is more exploratory. However, it is the later one wherein style is embodied, for all its tentativeness.

Another aspect of the non-stylistic is that of the ‘post-stylistic’ – which, in Wollheim’s terms, consists of work done in the years after an artist’s individual style has collapsed. In this respect, the example of Guercino is cited – along with evidence that his individual vision become atrophied through the heavy influence of Domenichino and Roman classicism.

Figure 1.1 Paul Cezanne, Auvers, Panoramic View, 1873/1875; oil on canvas: 25 5/8 × 32 in. (65.2 × 81.3 cm).

Source : Mr and Mrs Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial, the Art Institute of Chicago.

Figure 1.2 Paul Cezanne, Le Chateau de Medan, c. 1880; oil on canvas: 59.1 × 72.4 cm. Source: The Burrell Collection, © Culture and Sport Glasgow (Museums).

There is also a third variety of the non-stylistic. It concerns those cases where an artist has developed a style, but encounters challenges to which it is not adequate. Wollheim uses the example of Hogarth’s supposed failure in trying to do history painting instead of his moralistic narratives, and then (more persuasively), the difference between Renoir’s stylized late kitschy nudes (influenced by Renaissance works and Ingres) and his earlier work.

The fourth and most complex example of the non-stylistic occurs in artists of the highest genius. An artist of the order of Titian, for example, has a style that ‘becomes like a personality . . . [It] appropriates his opponent’s style, or some part of it, which remains, for a brief moment, undigested within his own’.13 The result is not disappointing – like the Hogarth and Renoir, rather it is ‘harrowing’ and ‘short lived’ before Titian works through the challenge and reasserts his style.

5) It is interesting that in all the complex details of (4), Wollheim is talking about explanation based on the relation between style and non-style, rather than the change from one style to another. This is because, in his terms, a painter is best regarded as having one style, rather than a succession thereof. For Wollheim, it is because this position ‘goes along very well with, the view of individual style as something real, hence explanatory, that we should be extremely reluctant, without evidence of massive psychological disturbance, to multiply styles by departing from the maxim, One artist, one style.’14 Indeed, we should think of the artist’s style as no more susceptible to fragmentation or division than personality itself.

6) Finally, in terms of describing the expression of style, Wollheim distinguishes between style and ‘signatures’. The latter involve idiosyncratic touches and choices that are of ‘forensic’ significance in determining authorship of a work. What they are is relative to the methods and instruments that are available to the connoisseur. The distinction in question, here, is, according to Wollheim, a conceptual one. In his words, ‘Aspects belong to ...