![]()

1 A Little Solitaire

A popular Chinese magazine proposed, in a plot not unlike ‘The Manchurian Candidate,’ that Lewinsky had been sent to Washington when she was a child as a Cold War agent on a mission to entrap the president and destabilize the government. ‘Is Lewinsky with the KGB?’ inquired the headline… Meantime, the Syrian defense minister, too, announced that the affair was a Zionist plot. ‘Monica Lewinsky is a young Jewish girl that Mossad hired and pushed into working as an intern in the White House.’

Marjorie Garber, ‘Moniker’, in Our Monica, Ourselves: The Clinton Affair

and the National Interest, edited by Lauren Berlant and Lisa Duggan (New York University Press, 2001)

When Nixon needed to think, he picked up a legal pad and wrote outlines. Reagan composed letters. Clinton played solitaire.

George Stephanopoulos, review of Reaching for Glory: Lyndon Johnson’s Secret White House Tapes, 1964–1965, New York Times Book Review, 30 December 2001

A voice: ‘Raymond, why don’t you pass the time by playing a little solitaire?’ The question is a command, and the first trigger. The thin, dark-haired man takes up a pack of card and begins to lay them out. He turns up the Queen of Diamonds. It is the second trigger. Once it shows, as the dark-haired man will say when it is too late, ‘They can make me do anything, can’t they?’

The Red Queen

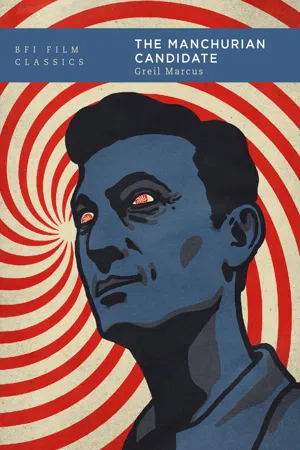

Eleanor Iselin (Angela Lansbury) and Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey), near the end (left); Major Ben Marco (Frank Sinatra), the end (right).

![]()

2 In 2001

Yet suppose instead of G.I. Blues he had been cast in The Manchurian Candidate, a film that captures the secret, encrypted side of Presleyan myth: the shellshocked, brainwashed soldier as a version of the post-Army Elvis, even as the widespread belief that rock ’n’ roll was a communist plot fits snugly into the movie’s conspiratorial milieu. And surely Angela Lansbury suggests a deliciously malign composite of Presley’s ruthless manager Col. Tom Parker and his adored mother Gladys – a living military-industrial Oedipus complex.

Howard Hampton, ‘Scorpio Descending’, Film Comment, March–April 1997

I tried to use Pavlov to get him to stop the war. Conditioning, behaviorism … ‘The Manchurian Candidate,’ have you seen it? …

I tried to get him to forge an association, ‘peace,’ ‘Quaker,’ ‘Mom.’ Now I see it was just the wrong series of associations. That mother.

Tony Kushner, obituary for Dr Arnold Hutschnecker, ‘A Shrink in

Paradise: Nixon’s confidant takes to the couch inside the Pearly Gates’, New York Times Magazine, 30 December 2001

When a movie has become part of the folklore of a nation, the borders between the movie and the nation cease to exist. The movie becomes a fable; then it becomes a metaphor. Then it becomes a catchphrase, a joke, a shortcut. It becomes a way not to think, and all the details of the movie, everything that made it stick in people’s minds, that brought it to life not just on the screen but in the imagination of the people at large, no matter how few or many those details might be, dissolve. The catchphrase contains the movie, and both become meaningless. Speak the words: they have become a way of saying, We’ve seen it all before. Unless you haven’t seen the movie.

When The Manchurian Candidate was presented at the San Francisco Film Festival in 2001, as part of a programme of films from earlier festivals – in this case, from 1962 – the crowd was mostly under forty. The picture was about a plot to assassinate a presidential candidate; taken out of circulation after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, it was rereleased both theatrically and on video in 1988 to great acclaim. Now it was about to unspool in the Castro Theatre, an ornately baroque movie palace with a steep balcony and an organ that emerges from a pit in front of the stage.

The theatre creates an atmosphere of anticipation; it sparks the feeling that, whatever might be on the bill, something extraordinary is about to take place. ‘This picture invites you in for a cool night of suspense and leaves you with no ground beneath your feet,’ the audience had been told, but as the film began, the titters and open laughter made two things clear: first, that it’s easy to forget that The Manchurian Candidate is, among other things, a comedy, and, second, that the people laughing had no idea what was coming.

![]()

3 In 1959

1961 Sinatra getting peeved at Kennedy Brothers. Being pushed aside because of Mafia connections. 9/24/61 Sinatra at Hyanis Port, then to Tell Robert and John to get off Sam Giancana case in Chicago… AT THAT POINT, SINATRA TOLD PRESIDENT KENNEDY ABOUT HIS INTEREST IN MAKING THE MOVIE ‘MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE’… This movie not too veiled threat to JFK after rejection by Bobby, Justice Dept…

Mae Brussell, World Watchers International Tape #860, 30 May 1998

The network of businessmen, agents and gangsters that links Bill Clinton to China’s Communist dictatorship is interwoven with every element of the greatest security disaster in American history. It as though the Rosenbergs were in the White House, except that the Rosenbergs were little people and naïve, and consequently the damage they were capable of accomplishing was incomparably less.

David Horowitz, ‘The Manchurian Candidate’, Salon, 21 June 1999

Published in 1959, Richard Condon’s novel The Manchurian Candidate had an unusual kind of success. It was simultaneously a bestseller and a cult book, casual reading for the public and the subject of hushed conversations among sophisticates: could this really happen?

The timing seemed safe. Dwight D. Eisenhower was nearing the end of his second term as president: ‘Things,’ as he once put it, were ‘more like they are now than they ever were before.’ Senator Joseph McCarthy had been dead since 1957. Five years had passed since the Senate that once followed his lead had cut him down with an overwhelming vote of censure. It was easy to forget the great days of 1950, when the then-obscure Republican from Wisconsin stood before a crowd in Wheeling, West Virginia, to charge that there were 205 traitorous members of the Communist Party in the State Department, and that the State Department knew it; when he rose on the floor of the Senate itself not two weeks later to speak for six hours in defence of his nation, then putting himself forward as the leader the nation deserved but did not have, challenging every agency of government and every citizen to stand in his light; when he bestrode like a colossus a land where, finally, all were equal – where no one was above suspicion. But in 1954 McCarthy had gone too far. He accused the Army itself of espionage, refused to reveal his evidence, and in an instant the cry ‘Have you no shame?’ turned into ‘The Emperor has no clothes.’ McCarthy had helped turn the United States into a haunted house where you could watch as your fellow citizens were named as turncoats, fellow-travellers, subversives, degenerates – where, even more thrillingly, you yourself might be seized from the gaping crowd – but now the show was over.

The nation turned away from the false charges, from the threatened, bribed or merely lying witnesses, from the whole industry of exposure, and everyone awoke from what all were happy to assure each other had been like a dream. But what if? Condon was now so playfully asking in his book – what if Joe McCarthy was really working for the Russians and the Chinese, for the very Communists he was supposedly attempting to destroy? And what if behind such a man lay a genius even more evil than he – say, the senator’s own wife, pulling his strings? And what if, in the conspiracy they served, there was the wife’s own son, like other American GIs taken prisoner during the Korean War somehow made to turn against his own country, but here far more profoundly, psychologically remade as an assassin-in-waiting, with no knowledge of the role he is to play? And what if his role is to kill in just such a manner as to propel Condon’s putatively anti-Communist demagogue into the White House, so that he might turn the country over to its enemies? And then the big question: could anyone stop a conspiracy so brilliant, so perfect, so absurd, that no one would believe it?

That was Richard Condon’s game in The Manchurian Candidate, and the novel was so purposefully crass, so self-consciously superior both to its tale and its audience, that you didn’t have to believe it. There was one moment when the book seemed to go through its own looking glass – when, as you read, you could imagine the country looking at itself. ‘This country is going to go through a fire like it has never seen,’ the senator’s wife says to her son in words that will be wiped from his mind as completely as any sense of what he has become. ‘Time,’ she says, ‘is going to roar and flash lightning in the streets, Raymond. Blood will gush behind the noise and stones will fall and fools and mockers will be brought down. The smugness and complacency of this country will be dragged through the blood and noise in the streets until it becomes a country purged and purified.’ But that was an odd break in the underlying contempt of the book for its own actors, in the fog a writer leaves behind when he is bored with his own story – where, in Condon’s pages, he cannot even summon enough respect for his characters to allow them the stage they supposedly occupy, when the nation the writer’s Joe McCarthy is supposed to command turns into ‘a group for anthropologists’, gathering from ‘ten thousand yesterdays in the Middle West and neolithic Texas’. They didn’t scare the reader, and neither did the book. That the story would lodge in the nation’s pysche and stay there was the work of other hands.

![]()

4 In 1954

If you come in five minutes after this picture begins, you won’t know what it’s all about!

Poster for The Manchurian Candidate, 1962

It’s 1954. Major Ben Marco of the US Army, played by Frank Sinatra, is lying on his bed, fully clothed in his uniform, dreaming the same dream he dreams every night. He’s sweating. As his lips twitch, the camera moves in and we enter his dream.

We’re in an old hotel in Spring Lake, New Jersey; a meeting of the Ladies Garden Club is in progress. On a small stage, one Mrs Henry Whittaker, on her feet, is speaking from behind a small white table; seated on either side of her are all the members of the patrol that Major Marco, then Captain Marco, led in Korea in 1952. The soldiers look bored out of their minds. The talk they’re listening to, that we’re listening to, is beyond boring: ‘Fun with Hydrangeas.’ The scene is striking – the ghastliness of Mrs Whittaker’s floral print dress is topped only by her hat – and you only subliminally register what’s off about it. Something in the way Mrs Whittaker is speaking is too harsh. She’s disdainful,...