- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Babette's Feast

About this book

On the face of it, Gabriel Axel's Babette's Feast (1989) is a film in which the eyes – and mouths – of religious zealots are opened to the glories of the sensual world. It is a critique of what Nietzsche called life-denying religion in favour of life-affirming sensuality. But to view the film in that way is to get it profoundly wrong. In his study of the film, Julian Baggini argues that Babette's Feast is not about the battle between religiosity and secularity but a deep examination of how the two can come together. Baggini's analysis focuses on themes of love, pleasure, artisty and grace, to provide a rich philosophical reading of this most sensual of films.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Mortal Illusions

Vanity of vanities, all is vanity.

Part of what motivates the religious sensibility is a sense of how all mortal endeavour ends in dust. From this realization springs the longing for salvation or redemption, something that will stop our lives being lived in vain. Understanding, coming to terms with, and overcoming this sense of futility is arguably the central concern of every major philosophy and religion.

In the Western tradition, the two main strategies for dealing with this are either embracing our mortality with all its flaws or to look to a life to come. Babette’s Feast shows us the perils of both alternatives by examining the key divergences in paths taken by its main protagonists.

When young and beautiful, the two sisters both have suitors, whom they ultimately spurn. Filippa is a gifted singer who is taken under the wing of a great French singer, Achille Papin, who acts as her tutor. Papin goes to the Jutland coast following acclaimed concerts in Stockholm, in search of solitude and untamed nature. Papin’s embrace of the passion and sensuality of music, however, proves too much for Filippa’s puritanical sensibilities. One clumsy kiss and Filippa cancels her music lessons, turning her back simultaneously on a man who loves her and a potential career as a singer capable of bringing immense pleasure to many.

The candlelit living room after the decision to end the lessons is a sorry, wordless scene. Filippa is unable to concentrate on her knitting. Her father, the ‘Pastor and prophet’ who founded the Lutheran sect they belong to, looks up from his book at her, a frown perhaps indicating disapproval that she clearly has some regret. Her sister looks at her with more sympathy though without clear understanding. Seeing her gaze, Filippa is uncomfortable and turns back to her knitting. She has chosen to let something powerful pass and the decision does not sit entirely comfortably.

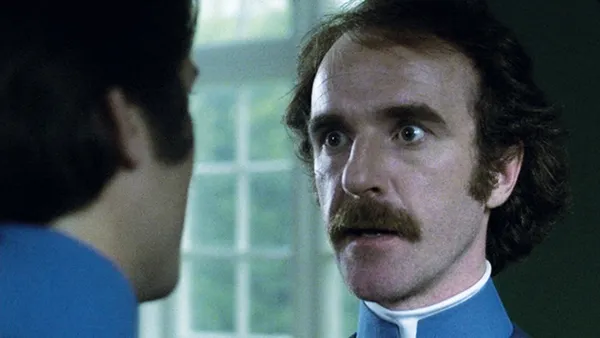

Sparks between Lowenheim and Martine fall on damp ground.

Martine’s young love is an evidently mutual attraction with the young soldier Lorens Löwenhielm, sent by his disappointed father to stay with his aunt in an attempt to shake him out of his indisciplined, dissolute, debt-ridden ways. What stands between them is simply Martine’s devotion to the religious mission of her father. Without ever explicitly discussing the possibility of marriage, it becomes evident that it just can’t happen. We’ve already seen her father turn away suitors saying ‘In this calling of mine, my two daughters are my right hand and my left. Would you rob me of them?’

When Löwenhielm leaves Martine and the village to pursue his military career, he tells her with more regret than resignation, ‘I am going away for ever and I shall never, never see you again. For I have learned here that life is hard and cruel, and that in this world there are things that are impossible.’ Martine looks troubled by this, seemingly aware that something bad is happening but not able to fully comprehend it. On hearing his declaration, she turns her gaze away from him, as though she is not able or willing to look the meaning of worldly love itself in the face.

‘I am going away for ever and I shall never, never see you again. For I have learned here that life is hard and cruel, and that in this world there are things that are impossible.’

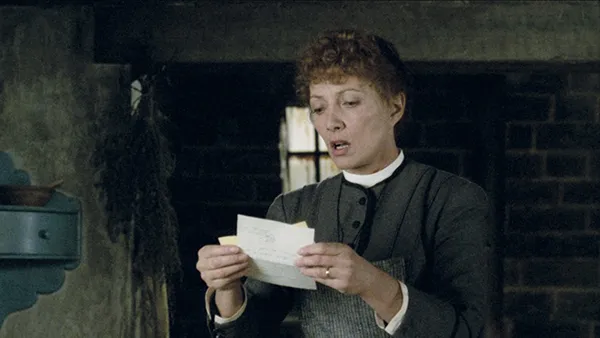

We have reason to believe she never quite overcame her longing. When on the day of the feast, Filippa reads a letter from Mrs Löwenhielm saying that she has received an unexpected visit from her nephew, Lorens, it is as though Martine awakes from the mechanical trance in which she has been preparing a wreath, looking briefly into the distance as though it were the past. She brings some of the wreath’s foliage to her nose, as though the sweet fragrance of the sensuous world had suddenly come back to her.

Does Filippa have any similar regrets? This is less clear. When Papin writes to them many years later, Martine begins to read his letter out loud but when he starts a sentence ‘For 35 years, Miss Filippa …’ she stops and passes it to her sister to continue. Filippa reads, ‘I have deplored the fate that kept your voice from filling the Grand Opera House in Paris.’ Throughout this, Filippa remains calm and seemingly unaffected. It is Martine who takes off her glasses and looks into space with an expression of such deep sadness that it seems the only reason she is not crying is that she has been long resigned to her losses.

The two sisters chose their celibate, religious life, the only one they had been prepared for. Anything else would have been a betrayal of their father, who was named after Martin Luther and his fellow reformist Philipp Melanchthon. And yet they had seen a glimpse of something else and could not forget it. ‘Do you remember that silent young man who appeared so suddenly, and vanished just as suddenly?’ Filippa asks her sister one day as the still young girls are preparing for bed. Martine turns round, pausing for several seconds before she replies ‘yes’, clearly remembering very well indeed. Again, it seems Martine is the one who finds it hardest to accept what has passed them by.

‘Goodbye, my life. Goodbye, my heart. Goodbye, my hopes.’

‘I will think of nothing but my career, and some day, I shall be an important figure in the world.’

The two men pursue their worldly ambitions, but without full conviction. When the Pastor delivers the note ending Filippa’s singing lessons, Papin is still singing and dancing for joy alone in his room. As the Pastor trudges back home, the singing stops, telling us Papin has read the note. We next see him sat at his table, still singing, but now with sadness. ‘Goodbye, my life. Goodbye, my heart.’ He adds, no longer singing, ‘Goodbye, my hopes.’ When we next see him he is setting off in a little rowing boat for the port of Frederikshavn, the waves beating him back as though the sea itself were reluctant for him to leave.

Löwenhielm had seen a glimpse of something purer and could not return to his soldier’s life unchanged. We have seen snippets of his life, and the world of the officers’ mess looks one of boredom, routine and petty plays for status. He is no longer like the other young officers, able to boast about their love affairs. Seen through others’ eyes, it seems pitiful to him that he had been ‘defeated and frustrated by some pious melancholics who can’t even afford salt for their porridge.’ And so he resolves to forget it all, to look forward, not backward. ‘I will think of nothing but my career, and some day, I shall be an important figure in the world.’

Many years later, both these men come to see their achievements as somewhat hollow. Papin’s initial despondency at Filippa’s rejection seems to be vindicated. In his letter to the sisters many years later, he writes that he is ‘a lonely, greying old man, forgotten by those who once applauded and adored me’ and asks ‘What is fame? The grave awaits us all.’ But implicit in this is the suggestion that Filippa was perhaps not mistaken to turn her back on a musical career. ‘I feel that it is you who chose the better path in life,’ he writes, albeit on the mistaken assumption that she would now be ‘surrounded by a happy swarm of children’. Yes, she would have thrilled audiences and become famous. But she too would have become forgotten and ignored as she aged and other younger singers came behind her. Papin’s excitement at her youthful promise would have turned to disappointment at its passing from potentiality, to actuality, to history. All dreams of worldly success seem vainglorious.

‘Vanity of vanities. All is vanity.’; ‘I have achieved everything you dreamed of, and satisfied your ambition. But to what purpose?’

Löwenhielm’s military life seems equally empty to him as he prepares for the film’s climactic feast, quoting the famous line from Ecclesiastes – ‘Vanity of vanities, all is vanity’ – as he looks at himself in the mirror. The image says it all. He is in the full uniform of a general, a man of power and prestige. His life seems to have been a success. He is popular in the royal court, where piety has become fashionable and he is able to make use of the Pastor’s teachings. (A book of his collected sermons is among the Queen’s favourite reading.) He has married a lady-in-waiting to the Queen and seems very happy with her. Yet the pomp cannot disguise his wrinkling skin, his greying beard, and the sadness in his eyes. For all he has achieved, he is now back in his aunt’s house, as alone as he ever was, only with more of his life behind him than ahead of him. Addressing his younger self, he says ‘I have achieved everything you dreamed of, and satisfied your ambition. But to what purpose?’

However, the hollowness of the men’s achievements does not vindicate the choices of the Lutherans. Their faces too speak of doubt and disappointment. Their sacrifices have not given them a better life on earth. They were made on the promise of a better one to come. ‘We will be rich in the next life,’ says one of the faithful at the feast. Even to say this suggests that a rich life is the ultimate good and therefore they have missed out on something by living life as austerely as they have. For most of the Western, twentieth/twenty-first century audience, this is a loss without future compensation. The sisters have staked their life on a false hope and so have missed out on much of what this world has to offer.

The equal and opposite impossibilities of a life that denies the temporal or the eternal, and the impossibility of asserting them both, comes straight from the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard, who we know influenced Dinesen. Kierkegaard described two spheres of existence, the aesthetic and ethical. The aesthetic is characterized by the philosopher Alastair Hannay as ‘a life ensnared in or dedicated to immediacy’.1 It is a life concerned with the immediate and the instant, with what is finite in the human condition. Kierkegaard gives us a snapshot of such a life in the chapter in Stages on Life’s Way entitled ‘In vino veritas’. Here we see young men feasting at a banquet but deeply unfulfilled. Their love affairs are empty because they are unable to make any sort of commitment, as that would require going beyond the now.

In the ethical sphere, the moment is of no consequence, only the eternal is. Living the ethical life requires a consciousness of and obedience to ethics as universal law. In realizing that we are proper subjects for these laws, we acknowledge the eternal within ourselves. But this is as unsatisfactory as the aesthetic because we cannot uproot ourselves from the temporal. The infinite and the universal are beyond human reach. Whenever we see an attempt to grasp the ethical and universal we actually see only something finite and particular, such as commandments engraved in tablets of stone delivered from Mount Sinai.

For Kierkegaard, the tension between the aesthetic and the ethical represents a paradox in the human condition that cannot be resolved rationally. The only way to meet our needs as both ethical and aesthetic subjects is to take a leap of faith into the irrationality of Christian religion, which asserts the impossible marriage of the two, embodied in the figure of Jesus Christ, God and man, finite and infinite, mortal and immortal.

Kierkegaard’s ‘spheres’ are like different parallel worlds coexisting on the same globe. In Babette’s Feast, it is almost as though they are given physical reality, with the sea as the unbridgeable chasm between them. The aesthetic is always across the waters. It is where the gastronomic delights arrive from, bringing the pleasures of immediacy to those who have rejected life in the moment. It is where Papin and Löwenhielm come from and go back to, after they have found themselves unable to make their accommodation to the ethical world of Jutland. It is where the sisters cannot leave, bound by their commitment to the absolute, the eternal.

‘10,000 francs!’; To stay or to go?

The sea’s most Kierkegaardian moment, however, is the brief scene where we see Babette walk down to the shore after her lottery win. She looks out to sea, no doubt thinking of France. Then she seems to make her decision. She turns around, back towards the village to ask the sisters’ permission to cook a celebration dinner for the Pastor’s anniversary, a ‘real French dinner’. In time we will understand that this is the moment when...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Mortal Illusions

- 2 Love

- 3 Pleasure

- 4 The Artist

- 5 Grace

- Conclusion: The Religion of the Immanent

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- Imprint

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Babette's Feast by Julian Baggini in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & European Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.