![]()

1

Solar Renaissance:

Through the burning-glass

Archimedean dreams

We begin with a fragment of a dream, recounted from the night of 10 October 1910:

I was once more working at chemistry in the University laboratory. Hofrat L. invited me to come somewhere and walked in front of me along the corridor, holding a lamp or some other instrument before him in his uplifted hand and with his head stretched forward … with a clear-sighted (? far-sighted) look about him. Then we crossed an open space …1

The dreamer was none other than Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), who sought to determine the causes and significance of this vision. Its ‘most outstanding point’ was the way in which his superior held the ‘lamp (or magnifying glass) before him, with his eyes peering into the distance’. Freud ‘knew at once’ this was a substitute for ‘someone greater’: ‘Archimedes, whose statue stands near the Fountain of Arethusa at Syracuse in that very attitude, holding up his burning-glass and peering out towards the besieging army of the Romans’. Freud had laid eyes upon this statue twenty-three days ago. Yet the principal cause of the dream was the news Freud had received that dream-day – his lecture theatre at the clinic was to relocate – reminding him of the diffident response he received from those above at the start of his academic career, when he had no teaching room to call his own. In the dream, therefore, Freud’s wish had been fulfilled: the dean who ignored his requests years before was, in the form of Archimedes, finally satisfying his obligations to give him a ‘ποῡ στώ’ (footing). This ancient genius and scientific pioneer, literally shining light into intellectual darkness, was showing Freud the way: Could any lesser thinker be worthy of the task? No wonder Freud admitted that these ‘dream-thoughts were not exactly free from ideas of … self-importance’ (Interpretation, p. 252n2).

Over the centuries, many thinkers, scientists, writers and artists have shared the powerful impression left by this image, striding confidently within the ‘footing’ it provided, including in the chemistry lab. Despite the implied illuminatory and/or ocular usage for the lamp or magnifying glass (‘lupe’) held by the professor, the burning-mirror or glass (‘Brennspiegel’) in Archimedes’s possession had a darker purpose: to focus the Sun’s rays upon the approaching Roman fleet, bringing about its pyrognostic destruction. For the pre-industrial age, the burning-glass (a term used interchangeably for mirror or lens) was perhaps the most evocative symbol of the absolute, almost divine power that could be unleashed by the application of knowledge, and had a fervent grip upon the early modern imagination.

Recent attempts to prove whether Archimedes constructed such optical devices have not been encouraging.2 The credibility of the story is of little concern to this study. What is crucial is the imaginative agency of this narrative in inspiring not only writers and artists but also natural philosophers, instrument-makers and artisans. Indeed, because the story is so doubtful and mysterious – requiring the exercise of scientific, technological and philological expertise to negotiate its many challenges – it has captivated the mind and hand for centuries. In particular, during an early modern period susceptible to the attractions of natural magic, Archimedes’s mirror offered a compelling story of knowledge facilitating power over nature, since it had secured control over the supreme source of light, heat and life. This episode of technological mastery was even figured as a kind of apotheosis, with Archimedes ‘transform[ing] himselfe into Iupiter; thundering downe … lightning’.3 The chapter will, therefore, begin by tracing the life of this myth into the heart of the Renaissance, allowing us to see how ambitions to collect and use solar energy reflect the intellectual, political and social aims of natural magic and science at this time. Later, the chapter will explore early modern relationships between material culture and the imagination, including the technologization of politics and theology, and its reflection in fantastical and satiric discourses.

As one would expect from such an evocative story of scientific genius standing up to military might, there are many accounts of Archimedes’s attempts to defend his home city while besieged by Marcellus’s Roman fleet (214–212 BC) during the Second Punic War. Several mention the use of an optical device – a six-sided mirror, according to Diodorus (c.90–c.30 BC).4 None of the earliest sources (Polybius, Livy and Plutarch) describe the use of burning-mirrors, or even fire more generally.5 However, in the late second century, Lucian (AD c.120–c.200) claims that Archimedes used ‘his science’ to burn the ships, while Galen (AD 129–c.200) notes the application of fire, either pots of flammable material or optics.6 By the sixth century, Anthemius of Tralles (c.474–c.558) refers to the ‘unanimous tradition that Archimedes used burning mirrors’; and Ibn Sahl (c.940–1000) and Ibn al-Haytham (c.965–c.1041) each have the Sicilian polymath in mind when they write their pioneering optical treatises.7 During the Renaissance, accounts of Archimedes’s achievements disseminated widely, and he became the role model for both the aspiring thinker and the inventor, at a time when the mechanical arts increased in their cultural value, partly because of such Classical exempla. The thermal optical work of other ancient figures (including Apollonius, AD c.15–c.100) was known, but various authors celebrated Archimedes particularly because he put his mathematics into practice, using ‘arte perspectiue’ to create fire.8 His ingenuity and military resistance elevated him to heroic status, exemplified by the topos of wielding the Sun’s power in battle.9 From the fifteenth century, technological developments allowed inventors to emulate Archimedes and find practical uses for optical innovations. For instance, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) made numerous drawings of machines designed to grind metal concave mirrors for burning, not imaging, properties, such as soldering together parts of large sculptures.10 A t the same time, burning-mirrors seemed to provide Leonardo with answers to his theoretical enquiries about the Sun’s heat.11

However, it was in the early modern books of ‘secrets’ (libri secretorum) that the imaginative possibilities of the burning-glass began to be emphasized. These technical books emerged from within the tradition of natural magic, and demonstrated a fascination with the power of technology over nature. Despite presenting themselves as ‘how to’ guides which explained how to produce extraordinary effects in a natural way, they also thrived on fantasizing tantalizing glimpses of wondrous, but apparently credible machines ‒ perhaps as a way of seeking preferment from a courtly audience. The relationship between natural magic and natural philosophy was, therefore, a complex one, with books of secrets arguably contributing to the foundations of the ‘Scientific Revolution’, helping experiment become more communal, and inaugurating a popular image of science as a ‘hunt after the secrets of nature’.12 Solar technologies seemed to play a special role within these changes because of the established and increasing importance accorded the Sun in different but coalescing communities, genres and disciplines (including astronomy, alchemy and metaphysics).

The most famous of the libri secretorum was the compendious Natural Magick (1558) by the Neapolitan aristocrat and dramatist Giambattista della Porta (1535?–1615), a book revised in 1589 to include the developing cultural sensation of optical technologies. Although there were many mechanical marvels which demonstrated the wonder of nature, arguably nothing came closer than solar technologies in conveying the sublime power that humans could harness through practical endeavour, since ‘catoptrick-glasses … shine amongst Geometrical instruments, for Ingenuity, Wonder, and Profit’.13 Della Porta offered applications of an incendiary kind: one could use them to ‘blow up Towers’ by laying gunpowder and preparing one’s glass at night ready to focus the Sun’s rays the next day (p. 362). Despite his own grand claims, della Porta was suspicious of those made about Archimedes. Nevertheless, he made sure to boast of having designed a glass which ‘exceeds the invention of all the Antients’, by burning at an infinite distance (p. 375). For della Porta, this ‘Artifice’ can be used to ‘inscrib[e] letters’ in the sky ‘as far as the Moon’ (p. 375), inaugurating a trope which associated the act of writing with the action of the burning-mirror.14

In contrast to della Porta, the story of Archimedes was central to the optical work of the Jesuit natural magician Athanasius Kircher (1602?–80), professor at the Collegium Romanum. Kircher was not the first, nor the last, of the Jesuits to be interested in thermal optics.15 Indeed, in the church dedicated to the Jesuits’ founder, St. Ignatius of Loyola, the monk Andrea Pozzo’s ceiling fresco (1691–4) depicts Ignatius’s glorification, and the rays emanating at this moment are reflected in an angel’s burning-mirror to form the Sun and Christogram, the symbol of the Society of Jesus.16 But Kircher took the imaginative and intellectual investment in solar technologies to a new level of intensity and sophistication. Despite the importance Kircher conferred upon the Sun’s light, however, his Jesuit affiliation demanded at least public loyalty to the Aristotelian, geocentric cosmos.17

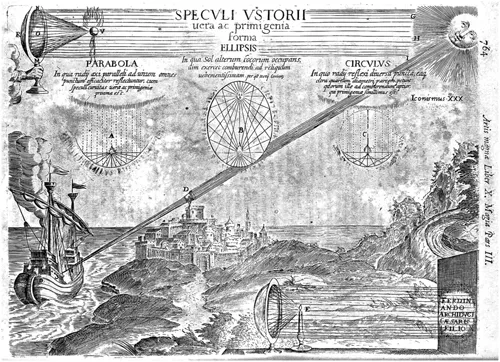

Kircher’s work on burning-mirrors was a kind of reconstructive archaeology, and included measuring the harbour at Syracuse itself (see Figure 1). Yet it was also innovative, demonstrating that increasing the number of plates upon which rays are reflected intensifies the radiation at the focus, suggesting that a number of smaller plane mirrors would function better than a single large parabolic, hyperbolic or elliptical one.18 He also showed that a parabolic was more efficient than a spherical mirror, because it concentrated its rays over a narrower area.19 Kircher published this work in Ars Magna Lucis et Umbræ (Great Art of Light and Shadow) (1646), which outlined many other optical wonders, including the camera obscura and, in the second edition (1671), the magic lantern. Especially following Kircher, the primal moment of Archimedes’s mirror harnessing the Sun’s power shone across the next century as a form of philosophical and cultural inspiration, establishing an interplay between knowledge of thermal optics as both the mastery of past narrative and the projection of future progress.

Figure 1 Athanasius Kircher, Ars Magna Lucis et Umbræ, second edn (Amsterdam, 1671), Plate XXX, facing p. 764. Wellcome Collection, CC BY.

Fittingly, the frontispiece to the second edition is a cornucopia of natural, artificial and divine Suns, illustrating Kircher’s metaphysics of light, which combined hermetic, Neoplatonic and cabbalistic ideas (Figure 2).20 At the top is a glimpse of the divine light, the bottom of a solar disc marked with the tetragrammon (‘YHWH’), whose emanations pierce a ring of clouds populated by the angelic host. This light hits the Book of Scripture directly, imprinting its power through the Word, and embodying ‘Auctoritas Sacra’ (Sacred Authority). These divine rays inspire the (Platonic) extramissive production of light from the eye of human reason (‘Ratio’), which seems to burn itself onto the page of another book of knowledge.21 Below these divine and divinely inspired Suns sits the physical Sun, personified as Apollo. With its own, independent luminescence (‘lux primigenia’), this material Sun produces three main beams: one reflected by the mirror of the Moon (itself figured as a technology emulating the Sun), held by Diana; the second refracted through a telescope to produ...