eBook - ePub

Literacy Coaching to Build Adolescent Learning

5 Pillars of Practice

This is a test

- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Literacy Coaching to Build Adolescent Learning

5 Pillars of Practice

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Helping coaches to define their roles, this resource provides practical tools and guidance about decision-making, design needs, professional development for teachers, collaborative relationships, and helping teachers use data.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Literacy Coaching to Build Adolescent Learning by Nancy DeVries Guth, Tamie Pratt-Fartro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Teaching Methods for Reading. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Learning From the Past: Vision for the Future

1

Historical Foundation

Literacy Coaches and Adolescent Literacy

Help! I am coaching, and I don’t really know what I am supposed to do.

—Recently hired literacy coach, 2008

What does a coach really do? This question has been asked by coaches, teachers, administrators, supervisors, and school board members. The list of job requirements and expectations is long, and the answers vary greatly. As an educational profession, we are not sure of the most advantageous roles for a literacy coach, but we are intrigued by the potential.

A short decade ago, coaching references in education primarily were related to athletic sports. Currently, if one looks up literacy coaching, over 300,000 English pages can be found on the subject. In the short span of 10 years, literacy coaching has gone from a relatively unknown topic to a “very hot” topic. For the past three years, according to the International Reading Association survey of “hot” topics, literacy coaching has led the list in “what’s hot” (Cassidy & Cassidy, 2009, p. 1). During the same decade, adolescent literacy has also emerged as a hot topic (Cassidy & Cassidy, 2008, 2009). The challenges associated with the topic are to develop a clear understanding of what coaching—specifically educational coaching for teachers of adolescents—involves and how it looks in practice.

It was with the advent of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), Reading First, and, more recently, the Striving Readers initiative that the term literacy coach came to prominence. There are now many varied definitions and job descriptions for literacy coaches and reading specialists. In this chapter, we give a historical overview of the coaching movement, which is intertwined with that of reading specialists and, in particular, the evolution of the coaching role at the secondary level. We believe that history informs current knowledge, and one must use lessons from history to inform current practice.

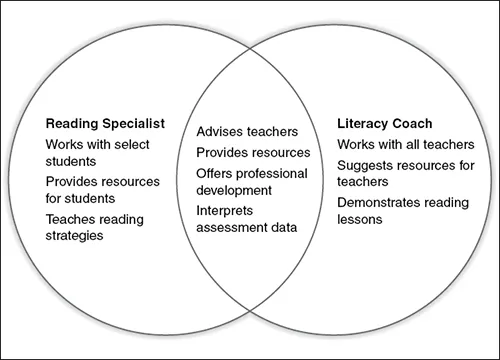

Evolving Roles: Reading Specialist and Literacy Coach

The concept of literacy coaching has been documented in educational literature for at least the past 20 years, stemming from social science research on the role of mentoring to improve instruction. Reading specialists (licensed teachers with additional training in reading) have historically been responsible for working directly with students experiencing reading difficulty; working with teachers to improve classroom instruction was seen as a minor aspect of the position. There has, however, been a definite shift in research and practice within the past five years: reading specialists are no longer viewed as the quick-fix remedy for individual students’ reading problems. Now, the research community recognizes the importance of classroom instruction as critical to providing each student the instruction necessary to succeed and to develop as a literate individual. The potential of the literacy coach to help each classroom teacher is recognized, but roles and expectations are not yet clarified.

Bean and Wilson (1981) trace the evolution of the literacy coach position through expectations for the reading specialist. As far back as the 1930s, reading specialists were generally expected to provide a form of job-embedded professional development; the reading specialist was expected to directly supervise teachers with the goal of improving the reading program (Hall, 2004). Even earlier, in the 1920s, the transition to content area texts posed problems for secondary students; Sturtevant (2003) cites a 1983 study suggesting that students—then, as now—were having trouble extending their reading skills from their reading books to their content reading texts. At that time, reading educators urged content teachers to teach reading skills along with content delivery.

By the 1960s, coaching had become a subtle expectation for the role of the reading specialist; a reading specialist was expected to be able to develop relationships with classroom teachers, parents, administrators, and students and be able to communicate effectively with all these people (Stauffer, 1967). That is, the role included the potential to improve the total reading and language arts programs of the school rather than focusing more narrowly on the achievement of individual students. Although the term literacy coach was not specifically applied to the reading specialist, this blended role is also implied in Bean and Wilson’s (1981) description of the reading specialist as a “colleagueship” in which the reading specialist and the teacher work as “associates and equals” bound together by the common purpose of improvement of student learning (Bean & Wilson, 1981, p. 7).

Yet the disconnect continued, especially at the secondary level. Ostensibly, reading specialists worked with struggling students, and middle and high school teachers focused on content rather than reading skills. In the Alliance for Excellent Education report, Sturtevant (2003) describes this disconnect throughout the 1960s and 1970s between actual school practice and recommendations of literacy educators. While literacy educators continued to push for increased attention to students’ reading skills along with teaching content area information, content teachers continued the focus on increasing subject area content. However, in the late 1970s and 1980s, federal funds became available to major universities to research secondary content area reading strategies. Many of these strategies are now appearing in textbooks for content teaching and appear in materials for professional development throughout the country (Alvermann & Moore, 1991; Sturtevant, 2003; Vacca & Vacca, 2008).

A New Focus: Adolescent Literacy

It is interesting to us that adolescent literacy is such a relatively new term, if not a new topic. As we’ve seen, educators have long been concerned with reading and writing beyond the elementary grades, but until recently, the focus of attention was on more narrowly defined content area reading, not the total literacy ability of adolescents (Lewis & Moorman, 2007).

The 2002 NCLB legislation was passed in the wake of research suggesting the importance of continued efforts in literacy for adolescent learners but did not focus on this age group. Five years later, in 2007, the Striving Readers Act was aimed at improving the reading skills of middle school–and high school–aged students reading below grade level and made competitive grants available directly to school districts. Striving Readers supports the implementation and evaluation of research-based reading interventions for struggling adolescent readers in Title I eligible schools that are at risk of not meeting or are not meeting NCLB adequate yearly progress (AYP) requirements and/or have significant percentages or numbers of students reading below grade level (Striving Readers, 2009).

Under the act, monies are available for qualifying schools to apply toward the salary of a literacy coach, who is tasked with assisting teachers to raise the reading performance of students at that site. The increased awareness of the need for attention at the secondary level is not reflected in funding levels, however. In 2006, $1 billion was allocated for Reading First (Grades K–3), whereas for Grades 6–12, the Striving Readers Act grant amount was a meager $29.7 million. This investment translates into $72.00 per child for Reading First, compared with 13 cents per student in Grades 6–12 (National Council of Teachers of English [NCTE], n.d.).

The three key components of the Striving Readers grants are as follows: (1) supplemental literacy interventions targeted to students who are reading significantly below grade level; (2) cross-disciplinary strategies for improving student literacy, which may include professional development for subject matter teachers and use of research-based reading and comprehension strategies in classrooms across subject areas; and (3) a strong experimental evaluation component (Striving Readers, 2009). School districts were encouraged to use these funds for professional development, including developing adolescent literacy plans for each school served, training school leaders in key components of the adolescent literacy plans, and the option to hire literacy coaches. Literacy coaches may be tasked with job-embedded, site-based professional development and teaching students in focused interventions, as well as tracking the school’s literacy progress.

The multiple expectations for the literacy coach embedded in the act may be seen as a return to the role of the reading specialist from the early 1900s—that of advising a school’s comprehensive literacy program and participating as a supportive colleague. Sturtevant (2003) calls the literacy coach movement a critical step in improving adolescent literacy. In her seminal piece, The Literacy Coach: A Key to Improving Teaching and Learning in Secondary Schools, Sturtevant (2003) notes the literacy coach can be a bridge between the content teacher and the reading material students are expected to read with mastery. Coaches are described as key players in a newly urgent initiative: improving adolescent literacy.

Current Expectations: Literacy Coach and Reading Specialist

The role of literacy or reading coach, according to the International Reading Association (2006), is as

a reading specialist who focuses on providing professional development for teachers by giving them the additional support needed to implement various instructional programs and practices. They provide essential leadership for a school’s entire literacy program by helping create and supervise long-term staff development processes that support both the development and implementation of literacy programs over months and years.

In many districts, the literacy coach and reading specialist are the same person; this model may work well for smaller school buildings (less than 1,000 students). Schools may also recruit a highly qualified, well-respected teacher to serve as a literacy coach, working closely with the reading specialist and administration. The coach can step into the classrooms, working shoulder to shoulder with the teacher, while conferring often with the reading specialist for additional research-based strategies or materials to assist in each student’s learning. Coaches can also help teams of teachers plan curriculum units, engage in lesson study, provide materials, and watch videotapes of students struggling with particularly challenging concepts. A key function of coaching is to help teachers identify the limits of student understanding and address their learning needs. A coach has the opportunity to see firsthand what teachers need to enhance their content and pedagogical knowledge. The coach may assist in organizing leadership teams and may design professional development to target areas of need (Anders, 1998; Sturtevant, 2003). According to a study by Blachowicz, Obrochta, and Fogelberg (2005), the literacy coach’s major job responsibility is “to provide professional development and to support teachers to improve classroom instruction” (p. 55).

The expectation for the literacy coach to provide professional development mirrors the expectation for the reading specialist as set out in the position paper Teaching All Children to Read: The Roles of the Reading Specialist (International Reading Association, 2000). In these new professional models, teachers and reading specialists (now coaches) are to work collaboratively in providing effective instruction for all students. To coordinate these services, schools must have reading specialists who can provide expert instruction, assessment, and leadership for the reading program. Specialists can become change agents, as suggested in the position statement, to work with teachers to create total school reform. Specialists and coaches often provide professional development for the school staff so all teachers are aware of important strategies and find materials to enhance literacy instruction and then follow up the training with modeling and coaching in individual teachers’ classrooms (Guth & Pettengill, 2005). The more recent position statement from the International Reading Association, The Role and Qualifications of the Reading Coach in the United States (2004), sets out the newly defined role of the reading coach or literacy coach in a parallel way:

Reading coaches frequently act as reading specialists when they provide leadership for school-, district-, and state-level reading programs. In the leadership role, they design, monitor, and assess reading achievement progress; they provide professional development and coaching for teachers and building personnel.

An historical organizer of literacy professional titles and expectations appears in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Professional Expectations

Thus, the literacy-coaching role has come full circle, encompassing many of the responsibilities of reading specialists in an earlier era and supported by a growing movement of coaching in education, not specific to literacy.

As mentioned, the literacy coach and the reading specialist may be the same person and, in the best case, should be a fully endorsed reading specialist. Cassidy and Cassidy (2009), in their annual survey, have designated the difference between literacy coach and reading specialist as follows:

A literacy coach or reading coach is a reading professional who focuses on providing staff development in reading/language arts to teachers. Literacy coaches or reading coaches model appropriate strategies, observe in classrooms, confer with teachers, and conduct staff development seminars. (p. 9)

Cassidy and Cassidy suggest, “the ideal is that the literacy coach works in one school and is a licensed reading specialist” (p. 9). In contrast, the traditional role of the reading specialist is focused more on struggling readers, working with the students individually or in small groups, administering diagnostic tests, and suggesting to teachers and parents ways to accelerate the student’s reading progress. Many combinations of each of these roles exist in each school system where literacy coaches are utilized.

We see the literacy and/or reading coach as one who creates ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- PART I. LEARNING FROM THE PAST: VISION FOR THE FUTURE

- PART II. GETTING STARTED: BUILDING ON THE FOUNDATION

- PART III. INTERIOR DECORATING: SUPPORTING THE PILLARS WITH TIME MANAGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

- Reference

- Index