eBook - ePub

Using the Language Experience Approach With English Language Learners

Strategies for Engaging Students and Developing Literacy

This is a test

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Using the Language Experience Approach With English Language Learners

Strategies for Engaging Students and Developing Literacy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Packed with lessons, sample texts, and strategies, this book helps teachers use ELL students' personal experiences to improve their oral language, reading comprehension, and writing skills.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Using the Language Experience Approach With English Language Learners by Denise D. Nessel, Carol N. Dixon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Curricula. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Value of LEA

for English Language

Learners

An Overview

We have long advocated the use of the Language Experience Approach (LEA) with students whose native language is not English. This instructional approach for English language learners (ELLs) makes sense as a method and works in the classroom. It is based on what is known about how oral language is acquired and about how the skills of reading are most easily learned. As a flexible approach, it meets the unique and varied needs of students who are learning English. In this chapter, we present the rationale for LEA and the key elements of the methodology. Succeeding chapters elaborate on and extend this overview.

LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND READING

The process of language acquisition cuts across language and cultural barriers (D. E. Freeman & Freeman, 2004; Krashen, 2003a; Lightbown & Spada, 2006; Pinker, 2000; Ritchie, 1978). A first language is acquired in informal, nonacademic settings through nonthreatening daily interactions with family and friends. Early acquisition can be hindered in settings where the language user is frequently corrected or reprimanded for incorrect speech (Gary, 1978); it is enhanced by adults’ eager attention to and acceptance of the child’s language use. Acquisition occurs most effectively when there is a need to know, the chance to try, and the freedom to err without penalty.

Several principles are as true for acquiring a second language as they are for acquiring a first language (D. E. Freeman & Freeman, 2004; Krashen, 2003a; Lightbown & Spada, 2006). Initially, second language acquisition takes place most effectively in informal, real-life settings where the learner freely interacts with fluent speakers of the target language. The more meaningful and purposeful the situations are to the learner, the better. For example, conversation about making needed purchases in a store is likely to further acquisition more effectively than a textbook exercise with little relevance to the learner’s life. Beginners need to use the new language in supportive, nonthreatening environments in which mistakes are accepted. For example, the novice benefits by talking with friends who ignore errors, focus on the intent of the communication, and encourage further speech. The novice must also have many opportunities to listen without being forced to respond, a situation that affords the chance to become familiar with the sound of the language; grasp as much as possible; and benefit from seeing gestures, intonation, and facial expressions as well as hearing words. Free to concentrate on listening rather than formulating a response, the language learner has a better chance of comprehending.

Those who have learned to read and write in their native language are likely to have an easier time learning to read and write in English because they already understand the purposes of these forms of communication and are adept at using them (Education for All, 2006, p. 203). Those who have not yet learned to read and write their native language have simultaneous challenges: learning English, understanding the processes of reading and writing, and developing skill in these processes. Some have additional challenges because the oral and written forms of their languages serve different purposes: Oral skills are not fully useful for comprehending written communications and vice versa. Learners who have become literate in such a language need to acquire new skills and perspectives when gaining literacy in English, a language in which the oral and written forms have similar features and serve similar purposes. If the native language of a learner does not have a written form, the learner has the additional challenge of getting used to the concept of written language while learning to read and write English.

In general, the reading process is mastered most easily when beginners read texts that are relevant to their lives, when the words of the texts are in their listening and speaking vocabularies, when the grammatical structures of the texts are similar to those they use orally, when they are learning in a supportive environment, and when they have many opportunities to practice with reading materials of their own choosing. These principles hold true when individuals are learning to read a new language.

LANGUAGE LEARNERS’ CHARACTERISTICS AND NEEDS

Learners of a new language share some characteristics despite their cultural and linguistic diversity. Their native language is no longer adequate for their daily needs or for the more complex language requirements of school or workplace. They must learn a new system of sounds and symbols that is somewhat, perhaps even radically, different from the system they have previously known. Younger learners, who usually acquire second languages with ease, may adapt readily to the new sound and symbol system (Ritchie, 1978). Older learners, however, may have never heard certain sounds in the new language, may have difficulty discriminating these unfamiliar sounds from other sounds, and may consequently have more difficulty reproducing those sounds. They may also be hesitant to attempt to use the new language if they feel self-conscious about their efforts. Several English sounds are difficult for certain ELLs. For examples of cross-language comparisons, see Refugee Educators’ Network (1997) and Trager (1982).

Aspects of students’ cultures can also influence their progress in learning English. For example, consider two students from the same country who speak the same native language but whose backgrounds differ. Although they share some cultural similarities, one has grown up in an isolated rural area where the people have little access to newspapers, books, or broadcast media, and the other has lived in an urban area, surrounded by books, magazines, television, and the Internet. The parents of the first have had little need to read and write and are not comfortable learning English, whereas the parents of the second are highly literate in their native language and are determined to learn English. Both sets of parents want their children to become fluent in English and achieve well in school, but they cannot provide equivalent language-learning support at home.

When learners have minimal responsibilities and can concentrate only on learning a new language, as is true for many young children and for older students who do not have family responsibilities, the learning can be enjoyable and satisfying even when the process is difficult. However, learners’ basic survival may depend on their use of the new language, as is true for many older students who are supporting families or who are the designated members of their families to master the new language. With such added pressures, learners’ lives are challenging and may even be frightening. Not only are they faced with mastering another sound and symbol system, but they must also understand new vocabulary and idioms as quickly as possible while adapting to American culture. Even if they have relocated with high hopes for a better life, they will experience at least some difficulties as they adjust. The older the student, the more unnerving the situation may be and the more unwilling the student may be to interact with native speakers, the very behavior that will increase the learner’s fluency. On the other hand, older individuals who are learning a new language may have more extensive life experience, greater motivation to learn, and more resourcefulness as learners, all of which can mitigate the challenges they face. In addition, their learning may be easier to the extent that they can make meaningful connections between their native language and the language they are learning.

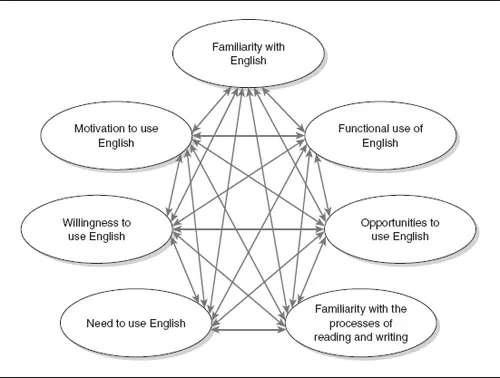

In sum, although learners of a new language may share some characteristics, they also vary considerably, depending on their age, their past experiences, their motivations, their current life situation, and key features of their native language. As Crawford (2007) points out, it would be best not to think of ELLs as a subgroup of learners at all, given that they vary on so many dimensions. Figure 1.1 contains a summary of key characteristics of ELLs that are salient in an instructional setting.

Figure 1.1 Characteristics of English Language Learners

As indicated by the graphic, each characteristic interacts with all the others. The result is a unique pattern for each individual. To illustrate how different patterns of these characteristics lead to diversity within a population of ELLs, here are some examples of recently arrived immigrants:

An eight-year-old boy is the youngest in a family of six. The parents have conversational fluency in English, having taken classes in the language before they immigrated to the United States. He has learned some English because his family members speak English as much as possible at home. They also socialize with the English-speaking families in the neighborhood, two of whom have eight-year-old sons who are in the boy’s class and who interact with him frequently in school and at home. The boy likes these friends, eagerly converses with them, and must use English when interacting with them.

An eight-year-old girl is the oldest of three children whose father speaks some English but has two jobs and is away from home much of the time. The girl’s mother speaks no English, is preoccupied with caring for the two other children, and relies on the eight-year-old to make telephone calls and handle other necessary communications, including exchanges with an English-speaking doctor who is treating one of the younger children. The eight-year-old girl has few English skills, but she knows her mother counts on her and willingly enters into conversations in English when she is needed. However, because many of the inhabitants of her neighborhood speak her native language, she does not have to speak English often.

An eight-year-old boy is one of five children whose mother and father speak a little English and who are eager for their children to learn the language and teach it to them. The boy is the most outgoing of the children, has made many friends at school, and uses English with them and with his teachers as often as he can. He is learning the language rapidly and prides himself on being able to teach his parents and siblings what he knows. He gives informal English lessons from time to time at home. When parents and siblings watch American television, they expect the boy to explain what is being said.

A sixteen-year-old girl is an only child. Her parents moved to the United States when the father was invited to be a guest professor at a university. He speaks English fairly well; the mother and girl are learning English with the help of a private tutor. The father’s colleagues invite the family to social events regularly, and through these activities, the girl has made one friend her age whom she sees in school. She is somewhat shy, and although she attempts to respond in English when addressed directly, she does not initiate interactions with native English speakers. Outside of school, she hears English primarily during her tutoring sessions.

A sixteen-year-old boy is the only child of a family that left their homeland as refugees with only a few possessions. They are being helped financially by a local church group, but neither parent has found work and both are having a difficult time adjusting to their new life. The mother and father stay together in their home most of the time and rely on their son to obtain food and other necessities for them. He is having an easier time adjusting to their new life but is often frustrated by not knowing the words he needs when shopping. He is an excellent soccer player and is in demand by the boys’ team at his school. Although playing on the team boosts his spirits considerably, the matches afford him few opportunities to hear or practice English.

A sixteen-year-old girl is one of three children in a family that has moved from an isolated, rural area in their home country to a densely populated neighborhood in a large U.S. city. The other children, both several years younger, are excited about their new life, but the shy sixteen-year-old avoids interacting with anyone outside the family. She seldom speaks in school and spends most of her leisure time at home, helping her mother with household chores.

A young man has just moved with his mother, father, and two younger sisters from a metropolitan area in his home country to a comparable city in the United States. As a high school graduate, he hopes to attend a university in the United States. For now, he works to help support the family. He has also enrolled in English classes at a nearby community college, which he attends two nights a week after work. He studied English for three years in high school and is now eager to refine his oral and written expression in preparation for enrolling in an American university.

A young woman has moved with her husband from a small town in her conflict-ridden native country to a small town in the American Midwest. They left behind almost everything and have begun a new life with the help of the members of the church that sponsored their immigration. She and her husband watched American television in their native country and learned some English from those viewing experiences, but neither understands English well and both are hesitant to speak English. They are together attending English classes offered by a local university with which their church has connections.

The school may not adequately acknowledge the high degree of diversity that exists in the ELL classroom because the primary goal is the same for all: to comprehend and use English fluently as efficiently as possible. The school’s focus is likely to be on teaching rather than on learning—that is, on presenting the established curriculum rather than tailoring instruction to the characteristics and needs of the learners.

Instruction can best accommodate to diverse learners when the classroom approximates a natural, real-world setting, filled with language. Such a context will give learners numerous opportunities to interact with fluent English speakers in meaningful situations. This is most easily accomplished when ELLs are given daily opportunities to interact directly with English-speaking classmates in pairs or small groups, both to socialize and to talk about what they are all learning. If most ELL instruction is provided in special language-learning classrooms, the students will need regular opportunities to talk and engage in academic work with English-speaking peers. A particular value of such interactions is that ELLs will hear words and phrases repeated many times. Such repetition ensures retention, and although it can be approximated with textbook drills or classroom exercises, it is much more meaningful and effective if it occurs in purposeful conversation with classmates.

Interaction with small numbers of native speakers of English also gives ELLs the chance to practice English. They will make errors in vocabulary and usage, and these can lead to embarrassment or frustration if an individual student is speaking in front of the whole class, but if students interact in pairs or small groups, the feeling of performing is reduced. Classroom practice stations or activity centers, designed for use by an individual or a few students at a time, can serve a similar purpose. Such centers can contain videos, audio tapes, computer programs, and popular songs, as well as books, pictures, and objects to stimulate observing, browsing, listening, talking, reading, and writing. Such centers will be especially effective when ELLs and native speakers work with the materials together. Such interactions are aligned with two key recommendations put forth for ELLs by the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE, 2006): that teachers recognize English language learning as a gradual process that builds on students’ native-language skills and that students in the classroom use English in realistic situations that are nonthreatening.

Besides needing many opportunities to hear and practice English, ELLs also need explicit instruction in reading and writing. Ideally, the instructional approach is an integral part of the natural communication setting that has been established in the classroom and is perceived as highly relevant, meaningful, and purposeful, with real communication as its focus. For example, many students will learn the English words to a favorite popular song much more readily than they will learn words presented in a textbook lesson, and they will more enthusiastically write if they are participating in a chat room or updating the class Web site or a personal blog than they will if they are completing a written exercise in a textbook. See Chapelle (2001) and Warschauer (1995, 1997) for examples of digital communication activities and their value for ELLs.

These principles are aligned with the following selected recommendations made in NCTE’s (2006) position paper on English language learning:

- Introduce reading materials that are culturally relevant.

- Connect readings with students’ background knowledge and experiences.

- Replace discrete skill exercises and drills with many opportunities to read.

- Provide opportunities for silent reading (in students’ first language or English).

- Read aloud frequently to students so that they become familiar with the sounds and structures of written language.

- Read aloud while students have access to the text to facilitate connecting oral and written modalities.

- Recognize that first and second language growth increases with abundant reading and writing.

TEACHING READING AS A COMMUNICATION PROCESS

LEA meets the needs of diverse ELLs while meeting the expectations of established literacy curricula. Three important features of LEA are central to its success as an instructional approach. First, students use their strengths as speakers and listeners in learning to read and write. Second, balanced attention is given to comprehension, word recognition, sight vocabulary, and composing so that students develop as well-rounded readers and writers. Third, the speci...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- About the Authors

- Introduction to the Language Experience Approach

- 1. The Value of LEA for English Language Learners: An Overview

- 2. Reading From Experience for Beginners

- 3. Reading From Experience for Intermediate Students

- 4. Reading From Experience for Advanced Students

- 5. Vocabulary and Word Recognition in an LEA Program

- 6. Writing in an LEA Program

- 7. Putting It All Together

- Appendix A: LEA and Selected State Standards

- References

- Index