There was a history to Gudmand-Høyer’s 1968 call for a new housing form. Already in 1964, he and a group of friends had begun discussing the possibilities of an alternative housing form. As Gudmand-Høyer (1984: 7) later put it, they were a ‘group of second generation Copenhageners with peasant roots, who had grown weary of the large city’. The detached houses and high-rise blocks of the suburbs were not seen as inviting. Rather, the group wanted to reconstruct some of the qualities that had characterised Danish villages before the enclosure (udskiftningen), and with inspiration from More’s Utopia and early philanthropic and cooperative housing projects, the aim was a community of some thirty families. The group found a plot of land near a forest on the outskirts of Copenhagen, but their plans were frustrated by the neighbours: ‘their fear of this odd project was so pronounced that they ganged up and bought the piece of land that should have been our access road’ (Gudmand-Høyer 1984: 7). It was against this background that Gudmand-Høyer in exasperation wrote his 1968 call for what became known as bofællesskaber, co-housing communities. By then, however, Danish society was in rapid change:

[O]ver the next month we received almost a hundred letters and loads of calls from people, who believed in the idea and wanted to live in such a place. It was overwhelming, now there were suddenly possibilities for creating not one but three or four co-housing communities. Journalists poured in. Now they suddenly found the theme highly relevant. But by then, of course, we had reached the middle of the year of the youth rebellion.

(Gudmand-Høyer 1984: 7)

As suggested by Gudmand-Høyer, Danish co-housing emerged as ‘child’ of the cultural, social and political changes associated with the 1960s and ‘1968’ specifically. And while many co-housing projects soon were faced with the economic crises of the 1970s and 1980s, the ideas germinated in a context of mounting prosperity and the ‘golden years’ of the welfare state. Ideas about alternative housing forms were not new, of course. Since around 1900, Denmark had seen the development of housing cooperatives, which questioned conventional notions of housing as either privately owned or rented (Larsen and Lund Hansen 2015). Somewhat closer to the everyday-life concerns of the emerging co-housing communities, some ‘collective houses’ (kollektivhuse) had been built during the 1930s and 1950s (Langkilde 1970; Nielsen 1979; on collective houses, see also Chapter 2). But the aim of these houses was particularly to rationalise domestic work within traditional families. The co-housing ideas were closer to the generally small communes (kollektiver), which from the mid-1960s sought ‘a rebellion against the isolation of the individual and the family’ (Hansen 1979: 54). Christensen and Kristensen (1972) estimate that there by 1971 were more than 700 of these communes in Denmark. And at a larger scale, Denmark in the early 1970s saw collective experiments such as Thylejren (est. 1970) in Norther Jutland and the ‘free city’ of Christiania (est. 1971) in Copenhagen (Buus et al. 2010; Thörn et al. 2011).

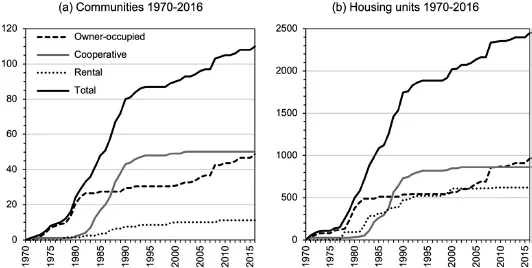

There were clear connections between the emerging co-housing communities and the wider phenomenon of communes. Indeed, the first recorded use of ‘bofællesskab’ appeared in a 1971 newspaper notice seeking people for a ‘commune-like co-housing community’ (kollektivlignende bofællesskab) (Anonymous 1971; Jarvad 1999). The word caught on. In the newspaper Information, which during the 1970s became a key channel for debates on all aspects of the new social movements, there were 78 entries using ‘bofællesskab’ in 1976, and the number peaked with 274 entries in 1981. During the 1980s, annual entries settled around some 150 before falling to 50–100 from the early 1990s onwards (Dagbladet Information, no date). Not least during the 1970s and 1980s, many of these entries were notices by people seeking (or seeking to form) some kind of collaborative housing arrangement. Possibly because it is less susceptive to prejudice, ‘bofællesskab’ was (and is) frequently used as a synonym for ‘kollektiv’ (commune). And well into the 1980s, both scholarly and more popular texts often had to clarify a distinction between the more widely known communes and the emerging co-housing communities (e.g. Andersen and Lyager 1984; Reich and Bjerre 1984). In spite of some affinities with communes and other collective ventures, however, the Danish co-housing communities were more mainstream. We shall here take note of three features of Danish co-housing, which emerged during the 1970s.

First, and in a sense defining, the co-housing communities that emerged during the 1970s were generally a housing form that combines individual housing units with substantial common spaces and activities aimed at everyday life. As already noted, there were (and are) some ambiguities in the use of co-housing as ‘bofællesskab’. But by the late 1980s, the term had generally assumed this meaning. For Navne (1987: 11), for example, co-housing communities (as distinct from communes) are characterised by ‘several, fundamentally independent housing units, which are inhabited by families, individuals or groups that cooperate on a range of activities in relation to their daily household work.’ A similar characterisation was used in a study by the Danish Building Research Institute (Vedel-Petersen et al. 1988) – and internationalised by McCamant and Durrett (1988). The material cornerstone of commonality is generally the ‘common house’ (or a similar space), which typically includes a kitchen and a dining room for common meals. To make room for this, spatially and financially, the size of the individual dwellings is often somewhat smaller than in ‘ordinary’ housing. In line with the ideas of Bodil Graae (1967; 1969), pioneering co-housing communities like Sættedammen (est. 1972) originally expected children to become a key common concern, but somewhat surprisingly, it was common meals that became central (Bendixen et al. 1997; see also Chapter 7).2 Reflecting a general trend in Danish co-housing, it is no coincidence that Overdrevet (est. 1980) made ‘Do you really eat together every day?’ the title of its silver jubilee publication (Ove R. Drevet 2005). (Many co-housing communities do not have common meals every day and participating is usually voluntary.) Reflecting on their spatial relationship to the surrounding society, a point to which we will turn next, Hansen (1979: 55) describes the early Danish co-housing communities as ‘collective individualists’. But given their private-common characteristic, this notion could equally be applied to the internal community of Danish co-housing.

Second, and partly to enable the private-common feature, Danish co-housing communities have since the 1970s generally (but not exclusively) been purpose built and have assumed a rather distinct architectural form and geography. During the 1970s, the so-called dense-low (tæt-lav) architecture was particularly dominant (Jantzen and Kaaris 1984). This style is associated with a 1971 architecture competition by the Danish Building Research Institute, and, as Nygaard puts it, dense-low in Denmark became ‘the architecture of the new Left’ and aimed to ‘build low to preserve relations to nature and dense to achieve social contact’ (Nygaard 1984: 227, 230). Dense-low was not confined to the emerging co-housing communities, but this architecture became somewhat of a hallmark; in the words of Hansen (1984b: 17), ‘a ring of dense and low buildings around some form of common space is the most general image of the contemporary Danish co-housing community’ (see also Hansen 1984a; and Chapter 8). Additionally, Hansen notes, these communities generally have a ‘somewhat solitary location’ in the urban periphery, and it is a striking feature of Danish co-housing communities that they were (and are) located mainly in suburban or quasi-rural environments (for a map, see Jakobsen and Larsen 2018). In part, this geography is explained by the price of land, but there are also other forces at play. As we have already seen, co-housing pioneers like Gudmand-Høyer sought away from the city, and this feeds into a wider ‘anti-urban’ sentiment of the 1970s. This is illustrated by two much-debated visions for a radical different Denmark. On the Left, the 1972 Langeland Manifesto outlines a vision of the country separated into thousands of loosely federalised settlements of 200–1,000 individuals (Reich and Prins 1977...