![]()

1 Introduction

This book explores discourse deixis in metafiction, investigating how discourse deixis works within and contributes to metafictional effects. Discourse deixis has remained a problematic category of deixis, with scope for further untangling. Metafiction has been the subject of much scholarly attention, particularly in the 1980s, but its linguistic workings have as yet not been investigated in great depth. Several metafictional techniques rely heavily on discourse deixis to create their metafictional effects. This book explores the intersection of discourse deixis and metafiction to offer new insights into both literary discourse deixis and the linguistics of metafictionality.

This introductory chapter begins with an overview of metafiction, including its development and common themes (section 1.1). The second section (1.2) reviews leading studies of metafiction and discusses the groundwork laid in some of these texts for an investigation of how metafictional effects are created. The next section (1.3) presents three of the main metafictional techniques: metanarration, metalepsis, and disnarration. The fourth section (1.4) introduces discourse deixis and its significance and role in metafictionality, through a brief illustrative discussion of an example from Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse (1988 [1968]). The fifth section (1.5) introduces the metafictional texts that will be explored in this book, and explains why these texts, in particular, have been chosen for this study of discourse deixis in metafiction. Finally, the last section (1.6) provides an overview of the book’s forthcoming chapters.

1.1 Mapping Out Metafictionality

The term ‘metafiction’ became critical currency in the late 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s as a means of labelling a particular type of fiction. It was coined by William Gass in his essay ‘Philosophy and the Form of Fiction’, originally written for a collection edited by Robert Scholes (1970) and then included in Gass’s own collection of essays, Fiction and the Figures of Life (1970). As Berry notes, Gass used it only once, to talk about the work of Jorge Luis Borges, John Barth, and Flann O’Brien (2012, p. 128). He used the term ‘metafiction’ to refer specifically to fiction “in which the forms of fiction serve as the material upon which further forms can be imposed” (Gass, 1970, p. 25). In later uses, as the term was adopted within literary scholarship, it came to mean fiction which overtly uses both its narrative form and its thematic content to explore the nature of fiction, and through it the nature of reality. As a descriptor, ‘metafiction’ is often applied to works like Muriel Spark’s The Comforters (1963) [1957], Gilbert Sorrentino’s Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things (1973), and Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions (1973). These novels variably involve pseudo-authorial narrators who intermittently comment on their acts of composition, characterisation, etc. (a kind of ‘metanarration’); characters or events which are presented as existing in the storyworld and then cancelled out in some way (a type of ‘disnarration’); characters who are aware of their fictional status; and/or some kind of crossing of the conventional boundary between the ‘level’ of narration and the ‘level’ of the storyworld (this awareness and this crossing being forms of ‘metalepsis’). One example of this unusual awareness and crossing of narrative levels is Spark’s heroine in The Comforters being able to hear the sound of her creator typing as the novel is composed, the sections which she hears being repeated within the narration of her experiences. The identifying characteristic of metafiction is its being “in constant dialogue with its own conventions” (Currie, 1995, p. 1), that is, its focused confrontation of fictionality and the conditions through which fiction is brought into being. Critical self-consciousness is not an incidental or minor feature in metafiction: rather, metafiction is dominantly, demonstratively, and constitutively engaged with its own conditions of existence, its parameters, its complexities, and its paradoxes throughout.

Some metafiction is, sometimes unfairly, criticised for merely offering a kind of literary navel-gazing. As Timmer asks, in relation to David Foster Wallace’s metafictional novella ‘Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way’, “what exactly could be the use of all this playing around with narrative structures for which postmodern literature is renown; is it just ‘fun’ for fun’s sake, and devoid of any humanness?” (Timmer, 2010, p. 106). Most metafiction is in fact ‘‘fun’’ precisely for the sake of humanness: it uses its self-reflexivity to address broader philosophical, social, and political themes (Hutcheon, 1988; Onega and Ganteau, 2007; Waugh, 1984). Much mid- and late twentieth century metafiction uses its self-reflexivity to embody and parody postmodern concern with the constructed and dialogic nature of reality and of identity, and with the relation between the subject and object, and between the self and other (Hutcheon, 1980; Waugh, 1984). These fictions employ a variety of metafictional strategies as part of a systematic and thematically integrated endeavour to confront ontological and epistemological uncertainties. The fictional form becomes both the medium and the parodic model for this interrogation of the subjectively constructed nature of reality.

Metafiction did not arise only with postmodernism, though. Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote (2003) [1605–1615] and Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (2003 [1759–1767]) are often heralded as the earliest examples of literature that is intensely metafictional. The birth and early development of the novel in the eighteenth century naturally saw a brief flourish of critical reflexivity, hence Tristram Shandy, Shamela, A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, etc.—works which demonstratively prioritise the medium of literary narrative as a thematic concern, albeit (like postmodernist metafiction) within a broader philosophical and socio-political context. These texts tend to interrogate the possibilities, impossibilities, and paradoxes of fictive narrative constructions at the same time as satirically exploring Enlightenment understanding of the self and social relations. For example, the eponymous narrator of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy ruminates—at surreal and satirical length and in a faux autobiographical fashion—on the influences upon his personality and identity, archly mocking the science and psychology of the day. Simultaneously, he also playfully subverts conventions of plot arcs and narrative progression, and frequently and explicitly comments on his failure in this regard, at one point even drawing line illustrations of the circles and swirls of digressions he has made over preceding chapters.

As the novel form became more established, its value began to be determined in its potential as a vehicle for social observation. Throughout the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, the novel was developed according to more conventionally mimetic strategies. Within texts of this era, metanarrative commentary still occurred, but only occasionally, and often contributing to didactic or ironic social commentary and/or affirmation of the illusion of narratorial insight into the story (thereby paradoxically supporting the mimetic illusion of the reality of the characters). Consider, for example, the following quotes from works by George Eliot:

Let me take you into that dining room […] We will enter, very softly […] the walls you see, are new. […] He will perhaps turn around by and by and in the meantime we can look at the stately old lady.

(Adam Bede, 2008 [1858], pp. 49–50)

One morning, some weeks after her arrival at Lowick, Dorothea—but why always Dorothea? Was her point of view the only possible one with regard to this marriage? I protest against all our effort at understanding being given to the young skins that look blooming in spite of trouble. […] In spite of the blinking eyes and white moles objectionable to Celia, […] Mr. Casaubon had an intense consciousness within him, and was spiritually a-hungered like the rest of us.

(Middlemarch, 1994 [1871–1872], p. 230)

In the first quote, from Adam Bede, the pseudo-authorial narrator addresses the reader directly as ‘‘you’’. Here, the narrator implies that she and the reader are both present together as quiet, discrete witnesses within the fictional scene. That ‘‘he’’ will ‘‘perhaps’’ turn around suggests that this pseudo-authorial narrator is observing, rather than creating and in control of, this scene. Ontologically impossible though this ‘presence’ is, this passage enhances the illusion of immediacy and the potential for a sense of immersion.

The metafictionality of the second quote, from Middlemarch, is more subtle and more complex. One the one hand, the (again) pseudo-authorial narrator appears to interrupt herself, affirming the illusion of her authorial role and power in her proclaimed proactive ‘refusal’ to focus on Dorothea’s viewpoint. The ensuing words could be read as a broader reference to and critique of marriage in fiction always being portrayed as the concern of the female characters, as in Austen’s novels, Richardson’s Pamela, etc. Read as such, it draws attention to the fictionality of this text while making a comment on gender politics in literary art. On the other hand, the implication that other characters, beyond Dorothea, have ‘‘view[s]’’ supports the impression that they are real beings, with histories and perspectives. This implies that the pseudo-authorial narrator is merely relaying, rather than creating, these views, which in turn affirms the illusion of mimesis.

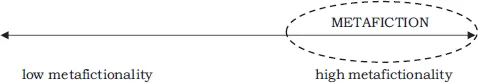

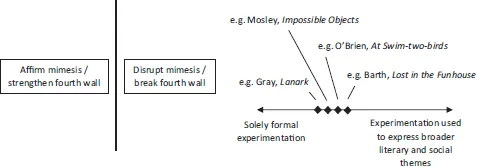

These quotes illustrate three important points. Firstly, metafictionality, as a quality of fiction, is scalar rather than binary. Alter and others have argued that all fiction bears the trace of its construction, reveals its fictionality, and undermines its own realism and conditions of believability and being. Alter goes so far as to suggest that “the realistic enterprise” of fiction, “from Renaissance Spain to contemporary France and America”, has been informed, “complicated and qualified by” the awareness of the illusory and even contradictory nature of literary realism and the ontology of the novel (Alter, 1978 [1975], p. x). Critical reflection within fiction upon the narrative medium can be traced through the Western tradition of narrative mimesis as far back as Euripides’ parody of the conventions of Greek tragedy (Alter, 1978 [1975], p. xi), and up to and through the ‘realist’ novels of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A reflexive awareness of literariness is therefore not particular to metafiction, but rather underscores much of the tradition of the novel as a mimetic form (see Figure 1.1). Secondly, metafictionality can serve sometimes to bolster, and sometimes to break, the ‘fourth wall’—and sometimes, paradoxically, can do both simultaneously. Thirdly, metafictionality can be used for commentary beyond ‘metacommentary’: that is, it can be used to reflect beyond (though via) that particular book to broader literary and socio-political contexts and concerns (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 Scale of metafictionality

Figure 1.2 Functions of metafictionality

Metafictionality is, then, neither rare in literature nor uniform in function. Metafiction ‘proper’, however, appears more rarely across the Western canon than incidental metafictionality. Metafiction is not merely occasionally self-reflexive, but dominantly so. It frequently and strategically breaks the fourth wall to disrupt and call attention to the illusion of mimesis and the nature of fictionality. Following the initial wave of reflexivity soon after the birth of the novel form, metafiction proper did not begin to flourish again until the late modernist and postmodernist eras. Woolf’s Orlando (1928) and O’Brien’s At Swim-two-birds (1939) are examples of late modernist metafictional novels. Both of these novels exploit metafictionality partially for socio-political agendas distinct to their eras, but both are also precociously infused with the pressing ontological and epistemological concerns that came to drive the metafiction of the postmodern era.

Western metafiction arguably peaked in the 1950s to 1980s. These were decades in which socio-ideological conditions imbued a hyper-awareness of the self and her/his relation to reality and the other, a crisis of faith in enlightenment systems of rationalisation and totalisation, scepticism of histories and master-narratives, anxiety over the mediating role of consciousness, and philosophical questioning of the possibility of communication and a shared ‘reality’. Metafiction is arguably the quintessential expression of postmodernism (Hutcheon, 1984, 1988; McHale, 1987; Waugh, 1984). The neatness of the marriage of metafiction and postmodernism is perhaps because the thematic concerns of the metafictional novels of the mid to late twentieth century are largely indistinguishable from the thematic concerns of postmodernism more broadly. Alternatively, it is potentially because metafiction’s textual and narrative modes afford it a uniquely concentrated self-reflexivity and critical enactment of these concerns. Hutcheon suggests that postmodern self-reflexive art

is perhaps a matter of finding an aesthetic mode of dealing with modern man’s experience of life as being unordered by any communal or transcendental power—God or myth—and his new skepticism that art can unproblematically provide a consolatory order.

(1984 [1980], pp. 18–19)

She argues that “the formal and thematic self-consciousness of metafiction […] is paradigmatic of most of the cultural forms of […] our ‘post-modern’ world” (p. xii).

One of the dominant themes within metafictional and postmodernist discourses is the dichotomy between the tendency, in narrative, theory, and human psychology, towards positivistic and comprehensive closure on the one hand, and the inevitably discursive, context-bound, pluralistic nature of meaning on the other. Postmodernism is marked by an undermining of the possibility and validity of a systematising master-narrative. Postmodernist theorists such as Lyotard (1983, 1984) state that there can be no valid claim of an ultimate truth or master-narrative, and take care to assert the contextually situated, constructed, and provisional nature of their own theoretical narratives (Hutcheon, 1988, p. 13, p. 20). However, they also note the internal paradox within any anti-totalising theoretical dogma: even the claim that there can be no ultimate truth is itself an implicit claim to a resolving cohesion and ‘truth’ of sorts, and therefore is an act complicit with the construction of totalising master-narratives. Metafictional novels both walk this tightrope and shine a spotlight on it, by problematising the ways in which fictional narrative can suggest the possibility of an author providing an ordered, cohesive, “totalizing scheme of explanation” (Hutcheon, 1988, p. 55) when this ‘explanation’ and meaning is entirely dependent on the reader’s context-bound subjective interpretation. Metafiction enacts the postmodern literary- theoretical exploration of meaning-value and the referent, of the proactive, retrospective construction of coherence, and of how far the author or text can manipulate, constrain, assist, obstruct, or disown interpretation.

Hutcheon observes that postmodernism “acknowledges the human urge to make order, while pointing out that the orders we create are just that: human constructs, not natural or given entities” (1988, pp. 41–42). The central paradox of postmodernism and of metafiction likewise is that its act of exploring and deconstructing orders, systems, and narratives is enmeshed within, and inevitably affirms and newly creates, orders, systems, and narratives. The paradoxical and provisional nature of narrative systems is not stultifying: the confrontation of construction does not paralyse the act of creating or engaging with narratives. Instead, this paradox, and its inevitability, is flaunted. As Hutcheon writes, “the contradictions of both postmodern theory and practice are positioned within the system and yet work to allow its premises to be seen as fictions or as ideological structures”. The self-reflexive critique works to expose “the tracks of the signifying systems that constitute our world—that is, systems constructed by us in answer to our needs” (p. 13).

A related theme commonly explored through both metafiction and postmodernism is the discursive nature of historiography. Many postmodern discourses recognise history as plural—as histories—and acknowledge these histories as fundamentally discursive constructs: the past is constituted by whichever versions of it are created and embedded within the discourses of the present. In historiographic metafiction, self-referentiality, problematisation of the author-function (as the determiner of the ‘true’ versio...