![]()

1 Introduction

1.1 The founding of Prosodic Syntax

A spoken discourse is formed by successive sentences and a sentence by a sequence of words. Thus, words and sentences must be combined in an orderly, regulated way and no confusion can ever be allowed. By ‘no confusion’ here we mean that there should be syntactic rules in a language which formulate the way in which words are combined into phrases and sentences. In this sense, it is quite natural for syntax to be free of phonology since words, regardless of how they are pronounced, will show up lawfully in sentences. It seems that syntax has little relationship with phonology. If anything, it is very likely that syntax interferes with phonology. For instance, the pause of a sentence is determined by its grammatical structure.

Pauses that break the syntactic structure of a sentence, like that of sentence (1b), are unacceptable. Therefore, it is traditionally held that the function and power of syntax are greater than that of phonology because the former can influence the latter while the latter falls under the domination of the former. However, people are not really free of phonological constraints when speaking. This can be illustrated by the most basic rule. The reason why we can only produce an utterance word by word is probably due to the fact that we can only articulate one sound only at a time. However complicated and comprehensive our thoughts may be, we have but one mouth and hence cannot produce two utterances at the same time. Though we may observe and conceptualize in a three-dimensional manner, we must speak in a linear manner. It must be said that this is due to the limits of our vocal organs. The linear constraints on phonology has determined the linear sequence of words in sentences. However, mankind’s pronunciation habits are not only subject to linear constraints. For example:

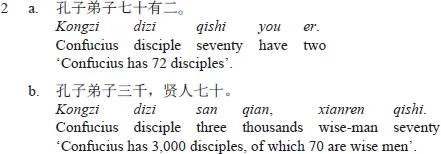

In example (2a), the pause pattern kongzi dizi/qishi you er 孔子弟子/七十有二 sounds most natural, with the quantifier qishi you er 七十有二 spoken together without a pause. However, the quantifier sanqian 三千 in (2b) cannot be spoken as an independent unit. The pause pattern kongzi dizi/sanqian/xianren qishi is ill-formed.

Sentences (2a) and (2b) are the same in terms of their linear structure and they can also undertake the same syntactic parsing. Why, then, can qishi you er be an independent unit in connected speech, while sanqian cannot? Perhaps the only reason here lies in the different number of syllables in these two sentences.

Even more interestingly, due to the different pause patterns, the word kongzi 孔子 from the phrase kongzi dizi 孔子弟子 ‘Confucius disciple’ in sentence (2a) is analyzed as a modifier, yet its counterpart in (2b) is not a modifier. This is because the required pause after kongzi 孔子 in (2b) disqualifies it as a modifier. Kongzi in (2b) can work as a modifier in theory but it can only be processed as a topic in practice. This demonstrates how differences in articulation can bring about different grammatical structures. In other words, we sometimes resort to the phonology of sentences to parse fully their grammatical structures. The ‘phonology’ discussed here of course does not refer to phonetic phenomena such as consonants and vowels, etc., but instead refers to ‘phonology’ in a broad sense, covering prosodic phenomena such as rhythm, metrics, stress and strong-weak. So far as this is concerned, syntax can never be independent from phonology. Further evidence is demonstrated in the following examples.

First, prosody can destroy syntax by altering the canonical constituent structure of sentences. For example, in the following verse line by Du Fu, a poet of great achievement in the Tang Dynasty, ba zhuyu 把茱芋 ‘holding a dogwood spray’ is a syntactic VO phrase but is separated in versification, with zui ba 醉把 actually forming one metrical unit.

It follows that the syntactic structure of a verse line sometimes gives way to its metrical structures. Another example is the four-character idiom yi dai shui 一衣带水 ‘be associated on close terms, separated only by a narrow strip of water’, which originally means ‘a river as narrow as a belt’. According to metrical rules (i.e., rules of pronouncing Prosodic Compound, see Feng, 1996b), this idiom must be pronounced with a pause exactly in the middle, namely, yiyi/daishui 一衣/带水, thus leaving many people unfamiliar with the meaning of dai 带. Once again, both the syntax and semantics of a linguistic construction can be sacrificed to assure a proper metrical structure.

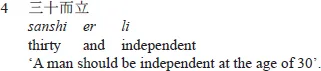

Second, prosody can override syntax by converting ill-formed syntactic forms into well-formed ones. For example, (4) is so well-known a usage in Chinese that it helps shape another idiom er li zhi nian 而立之年 ‘thirty years of age’.

The word er 而 was a conjunction at first but later combined with the word li 立 ‘independent’ to form a syntactic unit, and even a compound finally. Neither syntax nor semantics allows for er and li to form a unit, but prosody allows the two to make up a prosodic word (Feng, 1996b). Therefore, despite being ill-formed in syntax, erli 而立 is licensed in prosody, which demonstrates prosody’s overriding of syntax.

Third, prosody can constrain syntax by turning well-formed syntactic forms into ill-formed ones. For example, both zhongzhi huacao 种植花草 ‘plant flowers’ and zhong huacao 种花草 ‘plant flowers’ are perfectly grammatical in Chinese, yet *zhongzhi hua 种植花 ‘intended reading: to plant flower’ is not. The ungrammaticality here cannot be properly explained in terms of syntax and semantics because *zhongzhi hua as a VO form is licensed in both syntax and semantics. Besides, there are also other legitimate VO forms like zhongzhi xianhua 种植鲜花 ‘plant flowers’, zhongzhi mianhua 种植棉花 ‘plant cotton’, zhongzhi juhua 种植菊花 ‘plant chrysanthemum’ and zhongzhi mudanhua 种植牡丹花 ‘plant peonies’ and so forth including many different kinds of plants and flowers. Then why is there a contrast of grammaticality between *zhongzhi hua and other previously mentioned VO forms? For this, neither syntax nor semantics can provide a convincing account. As a matter of fact, it is prosody that rules out zhongzhi hua since the [2 + 1] (σσ+σ) VO form is prosodically unacceptable in Chinese (for details see Section 1, Chapter 4). That is to say, prosody can deem sentences unacceptable that are otherwise acceptable in terms of syntax and semantics, once again demonstrating the power of prosodic constraint on syntax.

Fourth, prosody can force syntax to operate on some forms, which were originally beyond the application domain of syntactic rules. For example, jugong 鞠躬 ‘to bow’ is a simple word in Chinese. Syntactic rules normally do not apply between its two combining elements, namely ju 鞠 and gong 躬. However, there is actually a usage ju le yi ge gong 鞠了一个躬 ‘make a bow’ in Chinese. The same sort of thing happens to another simple word youmo 幽默 ‘humor’ because people can say you le ta yi mo 幽了他一默 ‘to make a joke with him’ in Taiwan Mandarin. There are countless more examples from Chao’s time, such as the word ticao 体操 ‘bodily exercise’ appearing as ti le yi tang cao 体了一堂操 ‘exercised a class of physical’ and the word junxun 军训 ‘military training’ expanding as jun wan le xun 军完了训 ‘to have finished military training’. There arises a question, then, about why syntactic rules can now apply within words, which has always been a syntactic ‘forbidden zone’? Chao offers an insightful analysis for this phenomenon.

For the meanings of the morphemes, cao le yi tang ti 操了一堂体 ‘exercised a class of physical’ would be far more logical. But as usually happens, phonological factors outweigh logical factors: the mere iambic rhythm of the V-O constructions forces ti into the role of verb and cao into the role of the object, logic or no logic.

(Chao, 1968, p. 432)

Chao’s proposal of phonological factors outweighing logical factors and of the forcing role of iambic rhythm clearly demonstrates prosody’s overriding of syntax and semantics.

Fifth, prosody can convert syntax by changing the original word order or forcing the syntactic component to change in nature. For example, in Classical Chinese, a wh-object was generally preverbal, taking the form of ‘he-V (何-V)’. The postposing of wh-object, namely ‘V-he (V-何)’, started during the Han Dynasty. This type of evolution (see Chapter 5 for details) was actually motivated by the shift of the nuclear stress in sentences and the appearance of disyllabic wh-words. As a further example, the prepositional phrase (PP thereafter) could appear either preverbally or post verbally in Classical Chinese, as evidenced by the appearance of the following two phrases, which both appear in Mengzi.

The two share the same meaning, but the PP yi yang 以羊 ‘with sheep’ occurs post verbally in (5) and preverbally in (6). However, after the Han Dynasty, postverbal PPs began to disappear. Meanwhile, the V1 in some [V1 NP] [V2 NP] forms began to be grammaticalized into a preposition. We know that prepositions in Chinese generally originated from verbs. This raises a question that previously has not been seriously considered: Why did the historical evolution of verbs to prepositions present the following three characteristics?

- A Striking link to time: change took place in abundance only after the Han Dynasty, not before.

- B Strict adherence to syntactic structures: it is generally the [V NP] forms that evolve into [P NP] forms.

- C Uniform directional orientation: it is generally the V1 rather than V2 that undertakes a grammaticalization in [V1 NP] [V2 NP].

The series of changes described previously are all syntactic transformations that were compelled by prosody.

In Chapter 5, we will observe how the shifting of nuclear stress (also normal stress) from the preverbal position to the postverbal position constitutes an important characteristic of post-Han Dynasty Chinese. Thus a plausible explanation for the afore-mentioned evolution would be as follows: The shift of the nuclear stress has resulted in the preposition of adjunct PPs and placed [VP1] of the form [VP1] [VP2] on a non-focal position, thus triggering the grammaticalization of V1 into a preposition. Such an evolution of V→P can never occur in [VP2] because [VP2] is assigned the nuclear stress, to be the focus of the whole sentence. That is to say, the syntactic changes that follow in Classical Chinese are all prosodically triggered.

| 7 | A: | [WH V] | → | [V WH] |

| B: | [V(NP)PP] | → | [PP V (NP)] |

| C: | [V NP] | → | [P NP] |

Sixth, prosody can expand syntax by activating potential syntactic operations to form new structures. As is illustrated in Chapter 2 of Prosodic Syntax in Chinese: History and Changes, all the bei constructions in Classical Chinese that can be interpreted as either [bei N] or [bei V] are generally disyllabic, such as bei-lu 被戮 ‘be executed’ and bei-gong 被攻 ‘be attacked’. In that period, there are no trisyllabic bei constructions like bei-weilu 被未戮 ‘not be executed’ and b...