![]()

1 Trade Union Strategy, Influence and Power in Contemporary Britain

An Introduction

Introduction

The book is guided by Hamann and Kelly’s (2004) four factors of influence, which are identified as shaping trade union decision-making as a theoretical framework.1 The book terms these factors as follows: (1) economic and political institutions; (2) union ideology; (3) employer, political party or state strategies; and (4) strategic choices of union leaders. By employing these factors, the book will combine broad structural, ideational and agency explanations that help us to understand and explain trade union decision-making. Accordingly, the chapter will begin by introducing Varieties of Capitalism theory in order to assess the structural and institutional change in advanced capitalist economies. This will provide a wider context to the political and economic institutional reconfiguration in contemporary Britain. As a direct consequence of the economic and legislative change post-1979, the chapter will outline the function of political action through the Labour Party as a channel for influencing the employment relations arena. The centrality of trade union strategy, agency, structure and ideology as factors in this process will be outlined.

Varieties of Capitalism

Economic and political institutions directly shape trade unions, employers and political parties both subtly and overtly. These institutions can increase or constrain the opportunities for trade unions seeking to attain positive outcomes in the employment relations arena. The structural constraints on trade unions have facilitated an intense academic debate to explain the causal factors resulting in cross-country convergence and divergence. The Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) approach gives credence to divergence between nation states. The main emphasis in the comparative work lies in contrasting Anglo-Saxon states (e.g. United States and Britain) with continental European and Asian models (Hall and Soskice, 2001). The approach has grouped capitalist systems, especially those of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), into several categories: Liberal Market Economies (LMEs), Coordinated Market Economies and Mediterranean Economies. Underlying each model are sets of institutional arrangements involving the state, employers and trade unions.

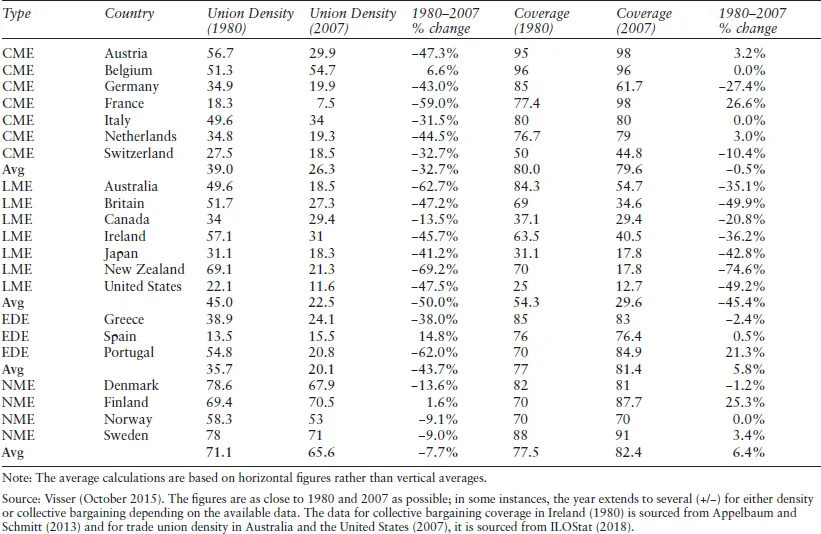

Hamann and Kelly (2008), Hyman and Gumbrell-McCormick (2010) and Appelbaum and Schmitt (2013) through the application of various time series data present findings that correspond with the VoC approach. Hamann and Kelly (2008) present statistics that show trade union density decline has been steeper in LMEs for the 1980–2000 period compared with fourteen non-LMEs assessed (median percentage point declines were 20.7 and 9, respectively). The differences within the non-LME group were ‘striking’, as the four Scandinavian economies (Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland) stand out as density rose in one of them and fell only slightly in the other three (−0.5 per cent average across all four countries over a twenty-year period). Over the 1980–2000 period, the gap between these Scandinavian economies and the other countries widened, leading to the conclusion that “there is no evidence of convergence” (Hamann and Kelly, 2008: 137). In a longer time-series presented by Appelbaum and Schmitt (2013), only one country showed a slight increase in trade union density pre-global recession (2007), which was Finland (1980, 69.4 per cent to 2007, 70.3 per cent).

Visser (1992) also drew attention to the comparable stability of trade union density in Scandinavia and Belgium compared with other advanced capitalist countries. The explanation for the difference was principally attributed to the role performed by trade unions in the provision of unemployment benefit—the ‘Ghent system’. All four ‘Ghent’ countries along with Norway remained the most stable countries analysed. According to the logic of the Ghent framework, trade unions can be institutionally insulated from economic pressures, but they are simultaneously vulnerable to changes in policy by the state. The assertion is corroborated by the sharp drop in trade union density statistics in Sweden from 76 per cent in 2005 to 69.3 per cent in 2010. The centre-right Swedish Government elected in 2006 made changes to unemployment insurance as the membership fees of most unemployment funds increased meaning a corresponding increase in the ‘total union fee’ (Kjellberg, 2011).

In LMEs, markets are ascribed as performing the role of managing relations between economic actors and capital is allocated primarily through stock markets. This is designed to ensure high levels of labour flexibility and capital mobility, which can facilitate sharp economic adjustments. Liberal markets are generally characterised by relatively low wages and low-skills levels in conjunction with weaker trade unions and less employment protection. These manifestations stem from the underlying structural conditions, principally greater degrees of deregulation, decentralisation and decollectivisation (Howell, 2004). In contrast, employers in coordinated market economies have an interest in strong trade unionism because they “form an essential part of productive strategies focusing on high-skill, high-quality export manufacturing goods” (King and Wood, 1999: 387). The statistics in Table 1.1 illustrate the specific set of economic and political dynamics in operation in LMEs, which have contributed to sharp decreases in trade union density and collective bargaining coverage. The table follows the same categorisation of advanced industrialised economies as Appelbaum and Schmitt (2013) except referring to Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland as Nordic Market Economies (NMEs) not Social-Democratic. In addition to LMEs, the other categorisations are as follows: CMEs (continental market economies) and EDEs (ex-dictatorship economies). Gallie (2009: 381) stated that Britain is the ‘clearest’ European example of a liberal market economy as density (−47.2 per cent) and bargaining coverage (−49.9 per cent) fell sharply over a twenty-seven-year period.2

Table 1.1 Trade Union Bargaining and Density 1980 and 2007

Deconstruction and Reconstruction

The notion of path dependence (Pierson, 1997) relates to a trajectory that becomes difficult to reverse. Incentives are created for actors to find solutions, which modify existing institutions rather than wholesale abolition or replacement. Accordingly, institutions will often persist for long periods and influence actors’ strategies in the short term to a greater degree (Ebbinghaus and Visser, 2000). It is entirely consistent, therefore, for specific political systems and bi/tripartite architecture to be retained in order to manage economic transformation. The process is principally organised and managed by government through social-pact processes as experienced in Italy, Ireland and Spain (Hyman, 2001). Howell and Kolins Givan (2011) highlighted that countries which use or reform existing institutions will also exhibit greater degrees of stability.

Pizzorno (1978) described a social-pact process as one of ‘political exchange’, whereupon the state offers greater economic involvement and increased legal rights to trade unions in return for commitments particularly on wage moderation. The level of political exchange is determined by the extent of corporatist mechanisms. A. Taylor (1989: 97), in a succinct description of the corporatist approach, stated that it was a framework whereby “economic interest groups (recognised as authoritative and representative by government) participate in the policy process”. Trade union participation through such an approach is characterised by three dimensions: (1) trade unions represent members within the process, (2) trade unions accordingly bargain with government on policy and (3) trade unions participate in the implementation of policy.

In Britain, collective bargaining agreements and corporatist structures had ‘shallow roots’ because they were “not anchored in legal or constitutional foundations as in many other parts of Western Europe” (Kelly, 2013: 181). Trade unions, rather than enjoying enshrined legal rights, historically had campaigned for the restoration of legal immunities. Economic transformation was structurally easier and made speedier by the absence of strong market coordinating mechanisms (Howell, 2004; Coulter, 2014). A majoritarian political system also limited the need for consensus through social-pacts as experienced across the continent of Europe.3 A structural factor facilitating economic transformation was the trend towards firm level bargaining through productivity agreements by multinational companies in the post-1945 era. These agreements were designed to provide firms with controllable and predictive wage costs in order to remove working practices considered inflexible by employers. Productivity agreements altered employment relations relationships from an externally constructed framework outside the firm, namely via national unions, national employers and the state, to internalised relations at the firm level (Gospel, 1992). The firm-centric structural shifts, supported in certain quarters by powerful trade unions in response to wage restraint measures during the 1950s and 1960s, would have profound consequences for a future Labour Government attempting to control inflation and minimise industrial action between 1974 and 1979. The tensions stemmed from attempts to centralise and control wages in tandem with decentralisation to the firm (Undy et al., 1981).

Due to these economic and political structural vulnerabilities, trade unions were brutally exposed in the post-1979 period as part of the Conservative Party’s response in government to the ‘Winter of Discontent’ (1978–79) strike wave. The neoliberal reform project of the Margaret Thatcher–led Conservative Government was directed towards decentralisation, decollectivism and the individualisation of employment relations (see Box A). In Britain, the introduction of neoliberal policies did not entertain any notion of consensual institutional deconstruction and reconstruction with trade unions (Wilkinson, 2007). It would herald a new settlement leading to the exclusion and marginalisation of trade unions. The Conservative Government brought forward the Employment Act of 1980, which contained measures to restrict the closed shop, limit industrial action picketing and reduce dismissal costs.4 This would also include the repeal of Schedule 11 in the Employment Protection Act (1975), which had guaranteed workers a statutory route to collective recognition when confronted by a hostile employer. Successive measures further restricted trade unions’ organisational abilities and immunities.5

Neoliberal reform included the abolition of the wage and trades boards through the Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Act (1993). This removed the remaining minimum wage protection for around 2.5 million low-paid workers. The Trade Boards Act (1909) had sanctioned tripartite machinery (i.e. government, employers and trade unions), which would characterise employment relations for decades. The Boards established a bottom-floor of minimum wages and conditions and facilitated collective bargaining. These agreements were legally enforceable in the industries where they were established. In those industries where the presence of trade unionism was strong enough, the government facilitated parallel structures in order to encourage stability in industry and the wider economy.

Box A What Is Neoliberalism?

Neoliberalism is a macro-economic strategy involving trade and financial liberalisation, fiscal discipline and the promotion of deflationary tactics. The approach necessitates structural reforms and an enabling institutional architecture particularly in the sphere of employment relations.

The dynamics identified include deindustrialisation, decollectivisation, decentralisation to the firm, economic deregulation including trade liberalisation (the European Union), flexible labour markets, individualisation of employment relations and privatisation.

Conservative Governments pursued an aggressive policy of privatisation in public industries and corporations, which would have significant implications for all trade unions. The list of major privatised industries included gas, electricity, water, nuclear energy, steel, telecommunications, coal and railways. In total, the number of people working in the public sector fell by 2.2 million from 7.45 million in 1979 to 5.23 million in 1995. The vast majority of the decline (1.7 million) resulted from privatisation, as the workforce of the nationalised industries and public corporations fell by 83 per cent (Howell, 1998: 295). The impact of the liberal market reforms was devastating for trade unions in Britain. Collective trade union membership fell from 13.2 million (1979) to 7.8 million in 1998, which brought density in the workforce to 29.9 per cent down from a peak of 50.7 per cent (1979).

New Labour: Continuation of Neoliberalism or Breaking With the Past?

The New Labour Government elected in 1997 complemented rather than conflicted with the Thatcherite reforms.6 Labour stated it would neither repeal the fundamental tenets of the Conservative employment relations framework nor return privatised industries to public ownership. New Labour’s political and economic reforms, despite being influenced by neoliberal dynamics, were distinct in comparison with the Conservative Governments (1979–97), as the book will evidence. The findings will challenge economically structurally determinist arguments regarding the inability of trade unions to meaningfully shape the employment relations framework.

The new approach was advanced through the notion of social partnership, which was informed by European approaches to employment relations (Ackers, 2002). Social partnership was based on the premise that firms are most successful when employers, managers and employees work together, which should be supported by the state. At the heart of the ‘Third Way’ narrative was a focus on supply-side initiatives such as skills, training and flexible labour markets (Wood, 2000). Social partnership would feature a more inclusive approach by the state and sections of the business community towards trade unions after the long period of exclusion under the Conservatives. Ackers and Payne (1998: 546) adroitly characterised the social partnership approach as consisting of two core elements: (1) it shifted the debate through ‘rhetoric of rights and reconstruction’ and (2) it appealed beyond union members wh...