![]()

1.1 The questions that must be answered to explore Chinese parts of speech

The issue of parts of speech is fundamental for grammar; the study of the grammar of a language requires the classification of its parts of speech. However, the issue has never had a satisfactory solution; many questions have not been answered and remain discrepant and controversial. The major questions are as follows:

1.Does Chinese have parts of speech? The question was debated in the 1950s, and in the 1990s some scholars questioned the existence of Chinese parts of speech.

2.What is the nature of a part of speech? Currently, it is universally accepted that its nature is distribution, but we cannot identify the grammatical function of any part of speech that is internally universal and externally exclusive. Can we say that the essence of a part of speech belongs to some other factors besides distribution?

3.What are the bases and criteria for classifying parts of speech?

4.How can parts of speech be determined at an operation level? With what standards should we classify various Chinese parts of speech? In the past, we relied on our language sense to identify the distribution norms for the parts of speech existing in our mind and did not provide proof for why we should identify these norms. We might even have skipped over the distinctions between some parts of speech. Is there any method for determining the distinctions between parts of speech according to the distribution of words before they are classified into parts of speech?

5.How can we deal with conversional words? For example, is a word such as 研究 (study) a verb and concurrently noun? This book aims at answering these questions. The author started to ponder these part-of-speech questions in 1986. Zhu Dexi and Lu Jianming undertook the National Seventh Five-year (1986–1990) Plan Key Social Science Research Project named “Exploring Modern Chinese Parts of Speech”, in which the author participated as a research team member. Later, he cooperated with the research team of the National Seventh Five-year Plan’s Key Natural Science Project named “Modern Chinese Grammatical Information Database”, undertaken by the Institute of Computational Linguistics at Peking University. The team members include Professors Yu Shiwen and Zhu Xuefeng, and they examined the functions of over 30,000 words. During the Eighth Five-year Plan, from 1991 to 1995, we continued to collaborate with the Institute of Computational Linguistics and increased the number of words and their functional examination scope on the basis of the Seventh Five-year Plan Research Project. The research team members included Zhang Yunyun and Wang Hui. The present book is based on the corpus of over 40,000 words examined, written, revised and proofread by many scholars, including Zhu Dexi and Lu Jianming, for more than a decade.

1.2 Difficulties in classifying Chinese parts of speech

For a long time, there have been no good solutions for the Chinese part-of-speech issue; the causes include both subjective and objective ones. Subjectively, in the past, we talked much about theory and did little actual work. As a result, we did not have a deep understanding of the real situation of parts of speech. (This book is based on the examination of over 40,000 words and is supported by plentiful actual materials.) Objectively, the Chinese language’s own characteristics make it difficult to classify its parts of speech. These features include the following:

1. Words do not have formal tags or morphological changes. 2. The constituents of modern Chinese are mixed at different hierarchies in different historical stages, making the grammatical functions and syntactic rules of a word complicated. 3. In general, words are multifunctional; this makes it more difficult to classify parts of speech according to their grammatical functions when words have no morphological changes. 4. The difficulties in parsing words make us unable to tell whether a certain usage belongs to a word or a word-formation. 5. It is difficult to judge the grammatical relations of a syntactic structure. Without morphological change, it is difficult to judge what function a word plays in its combinations; thus, it is difficult to use grammatical functions as criteria to classify parts of speech. For example, there are different opinions on whether 决心/完成任务 (determined to complete a task) is a predicate-object construction or a modifier-head construction.

To sum up, there is only one key cause for the difficulty of classifying Chinese into parts of speech, namely Chinese has no morphological changes.

Fortunately, previous and current scholars’ work paves a solid foundation for us. Based on past studies, the book will explore further in detail how to classify parts of speech in Chinese that has no morphological change.

1.3 An overview of studies of Chinese parts of speech

1.3.1 The formation and development of the framework of parts of speech

According to Yao Xiaoping (1999), Georg von der Gabelentz, a German who wrote Chinesische Grammatik, was the first to establish the complete Chinese grammar system. He classified Chinese notional words into nine parts of speech: noun, some relative (roughly equivalent to locative), numeral, adjective, verb, negative, pronoun, onomatopoeia and interjection. The Chinesische Grammatik, however, did not have much influence on China’s academic circle; rather, what greatly influenced the later Chinese grammar studies is Ma’s Grammar, by Ma Jianzhong (1898). Inspired by Western grammar, he classified the words of classical Chinese into the following nine parts of speech: noun, pronoun, verb, static word, state word, preposition, conjunction, auxiliary word and interjection. This system provided the basic pattern of Chinese parts of speech, and did not change greatly after that. After quite a long time, only numerals are separated from static words; modal particles were separated from auxiliary words; measure words and onomatopoeias were added.

Li Jinxi’s A New Chinese Grammar (1924) was the first of its kind because it was influential and studied systematically modern Chinese grammar. It classified Chinese words into five major parts of speech and nine basic classes: entity word (noun and pronoun), narrative word (verb), distinctive word (adjective and adverb), relative (preposition and conjunction), modal word (auxiliary word and interjection). Its basic classes, whose names are slightly different, are the same as those in Ma’s Grammar.

Lv Shuxiang’s Chinese Grammar Synopsis (1942–1944) classified modal particles (the scope is larger than the modal particles referred to generally, including the modal particle referred to subsequently, the modal adverb and interjection), while Wang Li’s Modern Chinese Grammar (1943, 1944) classified words into numeral and modal particle.

Modern Chinese Lecture by Ding Shengshu et al. (1952, 1953) classified measure word and onomatopoeia (including interjection), and pointed out the special classes of time word, place word and locative.

The Temporary Chinese Teaching Grammatical System (1956) classified Chinese words into 11 parts of speech: noun, measure word, pronoun, verb, adjective, numeral, adverb, preposition, conjunction, auxiliary word and interjection. The system was revised into The High School Teaching Grammatical System Synopsis (1984) and onomatopoeia was added to it. This system of 12 parts of speech had a rather big influence and has been adopted by most of the current dictionaries that tag parts of speech, except for a few dictionaries that separate modal particles from auxiliary words.

Zhao Yuanren’s Spoken Chinese Grammar (1968) has distinctive word as a part of speech, which includes demonstrative distinctive word (this, that), fractional distinctive word (each, all, another), quantitatively distinctive word (one, ten) and measurable distinctive word (integral, half, numerous).

Chen Wangdao’s A Synopsis of Grammar (1978) classifies copula, copulative and demonstrative.

Zhu Dexi’s Grammar Handouts (1982b) separated distinctive words from adjective; place word, locative and time word from noun; and modal particles from auxiliary words, totaling 17 parts of speech. Modern Chinese (1993), produced by the Department of Chinese Language at Peking University, classified state adjectives into state word, but returned place word, locative and time word to the category of a noun, totaling 15 parts of speech.

On the basis of the 17 parts of speech proposed by Zhu Dxi (1982b) and the 15 parts of speech proposed by Modern Chinese, compiled by the Department of Chinese Language at Peking University, the present book adds numeral, measure word and demonstrative, for a total of 20 parts of speech (see Section 1.5).

1.3.2 Two core issues for studying Chinese parts of speech

The first core issue is the relationship between part of speech and syntactic constituent; the second core issue is the criteria for classifying parts of speech. Almost all controversies stem from the two issues, and the reason why they trigger controversies has something to do with the fact that Chinese has no morphological change in the strict sense.

1.3.2.1 The relationship between part of speech and syntactic constituent

Because Chinese has no morphological change, which, therefore, cannot be used to classify parts of speech, we can only use the grammatical functions of a word. One of the characteristics of Chinese is that a word can function as many syntactic constituents. For these reasons, we have the questions of the relationship between part of speech and syntactic constituent: how does a part of speech correspond to its syntactic constituent? Specifically, there are three questions: (1) Does a part of speech correspond to its syntactic constituent directly or indirectly? (2) Is the correspondence one-to-one or complicated? (3) What syntactic constituents can a part of speech function as? The methods for answering the first two questions include the double-line system, the one-line system and the three-layer system.

The double-line system: This refers to the part of speech level and the syntactic constituent level. However, because a Chinese word is generally multifunctional, there are slots between part of speech and syntactic constituent. To resolve the slots, scholars use various methods, including the change in part of speech and the addition of functions.

The change in part of speech establishes the simple one-to-one correspondence between part of speech and syntactic constituent. For example, a noun should function as subject or object; a verb should function as predicate or complement; an adjective attributive; an adverb adverbial. If a word occurs at the position of different characteristics, it may be deemed to have changed its part of speech. Most of earlier works on Chinese grammar adopted this method. For instance, Ma’s Grammar proposed the theory that a part of speech functions in the guise of various syntactic constituents. If a verb occurs at the position of subject or object, then it functions in the guise of a noun; if it occurs at the position of attributive, then it functions in the guise of an adjective (static word). Chen Chengze’s An Initial Start of Chinese Grammar (1922) and Jin Zhaozi’s Studies of Chinese Grammar (1922) proposed the flexible use of parts of speech. Li Jinxi’s A New Chinese Grammar (1924) proposed distinguishing between parts of speech according to sentences. All these works use the change in part of speech to resolve the slot between part of speech and syntactic constituent. The Temporary Chinese Teaching Grammar System (1956) proposed the “nominalization theory”. In sentences such as 他的来使大家很高兴 (His coming makes everybody happy) and 狐狸的狡猾是很出名的 (The slyness of a fox is famous), 来 (coming) and 狡猾 (slyness) do not contain the meaning of substantial action or properties but regard them as “things”. They lose the properties, or some properties, of their verb and adjective forms, while acquiring some properties of a noun. We call this the nominalization of an adjective. “Nominalization” is a vague expression and does not clearly say that there is a change in part of speech, but in essence it is the same as the loaned part of speech and its flexible use. Because most Chinese words can function as many syntactic constituents without morphological change, although the method of changing parts of speech assigns certain syntactic constituents to a part of speech, it makes Chinese parts of speech changeable (Zhu Dexi, 1982c). As a result, words do not have their definite parts of speech, and we may even reach] the conclusion that “there is no part of speech without a sentence”.

The function addition method holds that there is a complicated correspondence between part of speech and syntactic constituent. A part of speech is multifunctional: so long as the meaning of a word does not change, the word belongs to the same part of speech even if it occurs at different positions. Although this method causes a word to have its definite part of speech, it causes a part of speech to have no definite syntactic constituents. In essence, it openly admits the slot between part of speech and syntactic constituent instead of denying it. During the debate on grammar innovation at the end of the 1930s and the early 1940s, Fang Guangdao proposed classifying parts of speech according to a generalized morphology, while Chen Wangdao proposed classifying them based on integrated structural functions. In doing so, they used the function addition method. Lv Shuxiang and Zhu Dexi’s Talks on Grammar and Rhetoric (1951) proposed that if the meaning of a word does not change, then its part of speech does not change. Later, what was meant by Zhu Dexi’s saying that a part of speech is multifunctional, was narrowed down slightly. 批评 (criticism) and 研究 (study) and so on, which are directly modified by nouns and function as the quasi-objects of predicate verbs such as 做 (do), 进行 (carry out), 加以 (conduct) and 有 (have) are considered nominal verbs. In this case, they are considered to be nominal. But Zhu Dexi still thought that 出版 (publication) in 这本书的出版 (the publication of the book) and 去 (going) in 去是应该的 (Going is obliged) have the properties of a verb.

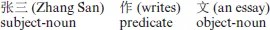

The one-line system: This notion was put forward by Fu Donghua in the 1930s. Because a Chinese word is multifunctional, the simple correspondence between part of speech and syntactic constituent must use loaned parts of speech. He held that it would be better just to presume that it is impossible to classify words into parts of speech and said that “if a word is not used in a sentence, there is no way to know its part of speech”. Therefore, parts of speech should be combined with sentence constituents. For example:

Actually, this view is a natural development of “distinguishing between parts of speech according to a sentence” and “there being no parts of speech without a sentence”. During the debate on Chinese parts of speech in the 1950s, Gao Mingkai also thought that Chinese had no parts of speech mainly because they should be classified according to the morphology of a word. Chinese has no morphological change and therefore has no parts of speech. Later, he changed his point of view and thought that “the morphological changes of a word, its combination capacity and syntactic functions etc. are all the external marks of its part-of-speech meaning”. Chinese has no morphological change, and its parts of speech can only be classified according to the use of a word. But because Chinese parts of speech are multifunctional, “a word can be used simultaneously as noun, adjective and verb” (meaning a notional word can appear at the positions of subject, predicate and attributive). Therefore, every notional word belongs to several parts of speech, implying that Chinese has no parts of speech (Gao Mingkai, 1960). Xu Tongqiang (1994b) thought that the parts of speech in Indo-European languages have a one-to-one correspondence to sentence constituents, thus causing the necessity to classify them. Now that one Chinese part of speech corresponds to many sentence constituents, this implies that Chinese does not have parts of speech at all. With regard to the theory that Chinese has no parts of speech, Zhu Dexi (1960) thought that, although the classification of parts of speech according to sentence constituents takes grammatical functions into consideration, “because selectional criteria are too loose and the method is too simple, parts of speech cannot be classified this way, instead reaching the conclusion that a word has no definite parts of speech. The entire error of this method lies in the fact that it assumes that there is a one-to-one correspondence between part of speech and sentence constituent . . . but as a matter of fact, the relationship between part of speech and sentence constituent is complicated”. If the one-line system is take...