This is a test

- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Arte Ambientale, Urban Space, and Participatory Art

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Working in 1970s Italy, a group of artists—namely Ugo La Pietra, Maurizio Nannucci, Francesco Somaini, Mauro Staccioli, Franco Summa, and Franco Vaccari—sought new spaces to create and exhibit art. Looking beyond the gallery, they generated sculptural, conceptual, and participatory interventions, called Arte Ambientale (Environmental Art), situated in the city streets. Their experiments emerged at a time of cultural crisis, when fierce domestic terrorism aggravated an already fragile political situation. To confront the malaise, these artists embraced a position of artistic autonomy and social critique, democratically connecting the city's inhabitants through direct art practices.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Arte Ambientale, Urban Space, and Participatory Art by Martina Tanga in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Contemporary Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

From the north of Italy, artists came, as called, to deliver a response to the socioeconomic downturn afflicting the small Sicilian town of Zafferana. It was September 1970, and they must have felt the summer heat abating and seen the long afternoon shadows retracting across the baroque façade of Santa Maria della Provvidenza, the town’s main church along Via Giuseppe Garibaldi. Energized by the hint of a fresh sea breeze, artists were eager to engage with the inhabitants of Zafferana and to see how they might channel their creative impulses into positive outcomes for this dispirited town.

A small village at the confluence of lava streams from Etna’s eastern craters, Zafferana was suffering from a decrease in population and agricultural productivity.1 Southern Italy had always lagged behind Italy’s productive north, but the conditions of disparity, poverty, and economic stagnation had become particularly acute since the “economic miracle” of the 1950s and 1960s.2 The town’s inhabitants had historically shown impressive resilience, rebuilding their houses many times after being damaged and even destroyed by the nearby volcano’s violent eruptions. The problems afflicting the town now, however, were different; it was not just about restacking the bricks and mortar but rebuilding the fabric of society. In the face of recent socioeconomic hardship, the municipal administration decided to try something new, an exhibition and a conference titled Interventi nella città e sul paesaggio (Interventions in the City and Landscape), organized by Florentine curator Lara-Vinca Masini and Roman architect, theorist, and historian Paolo Portoghesi. Architects and contemporary artists from across the country were invited to dialogue with the people and spaces of the city as a lived environment and to tackle its socioeconomic realities.3 Among others, artists Getulio Alviani and Ugo La Pietra came from Milan, Maurizio Nannucci from Florence, and Franco Vaccari from Modena.4 Upon arrival, Vaccari recalled that he felt overwhelmed by the deterioration of the city and was motivated to address it through his participation in the exhibition.5

These four artists were interested in the exhibition’s objectives, to engage with the urban environment and its socioeconomic condition. Though they might not have known it at the time, this concern was going to preoccupy them for much of the 1970s and beyond.6 Alviani and La Pietra knew each other, as both came from Italy’s industrial capital, while it is unclear whether they had a preexisting connection with Nannucci or Vaccari; certainly, they had never worked all together. Only La Pietra, of the four, had made artwork prior to 1970 that could be described as an intervention in the urban landscape: a temporary, ephemeral art project sited within the city and meant to engage the public.7

The exhibition was to follow a typical arrangement, a juried selection of the artwork with a prize given out to the best submission.8 Arriving in Zafferana, La Pietra, Nannucci, Vaccari, and Alviani suspected that the local judges had rigged the prize selection, endorsing local artists for political reasons.9 They also realized, much to their chagrin, that the organizers were marshaling a pleasant and uncritical exhibition intended to boost the local economy and tourist industry rather than address the city’s sociopolitical concerns.10 Feeling betrayed, the four artists rejected these pretenses, as they believed that contemporary architectural or artistic work needed to engage with the real experience of the environment.11

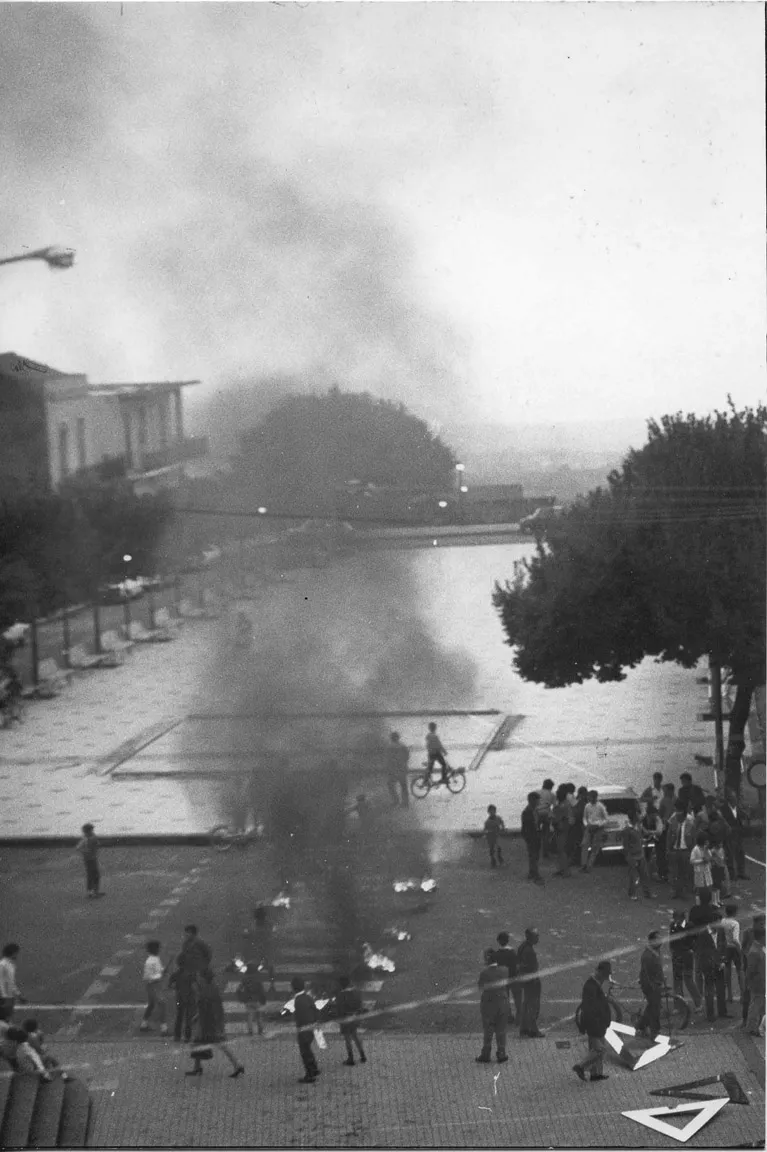

Impulsively, La Pietra, Nannucci, Vaccari, and Alviani decided to protest the exhibition and created their first collaborative urban intervention. Segnali di fuoco (Fire Signals) [Figure 1.1] featured ten car tires—five on each side—arranged along a pedestrian crossing in the city’s main square, Piazza Umberto I Belvedere, which the artists set on fire. From the documentary photographs, we see that dozens of passersby stopped to watch the conflagration and the billowing, dark smoke. Lighting tires in the manner of street protests, with their indelible images of blazing automobiles and shattered glass, the artists signaled an explicit rejection of the political and social situation in which they were invited to work.12 Moreover, associations with the volcano Etna, and the constant feeling of impending danger, must have also resonated with the artists and spectators. Certainly, the work had the air—and smell—of dissension. Using fire and smoke, the artists also evoked an ancient means of visual communication used over long distances, smoke signals, to alert people to danger. In effect, they were ringing the alarm for both the corruption of the exhibition and the venality endemic in the town’s administration, which was at the root of Zafferana’s socioeconomic problems. Ironically, even though this work existed outside the realm of the exhibition, it came closest to the original design of the show: art that engaged with the city and its inhabitants.

Establishing a complex, often polemical dialogue with the city and its inhabitants, Segnali di fuoco was an early example of Arte Ambientale (Environmental art). Artists and critics alike started to use the term during the 1970s to define the expansion of aesthetic practices out of museums and galleries and into streets and piazzas.13 This type of site-specific art engaged with the urban environment as a space of social relations.14 Art historian, curator, and critic Enrico Crispolti defined “Arte Ambientale [as] part of an urban context, where there are people, where you have an architectural context. It [was] active in that it hoped to change the space in which it [was] situated.”15 Moreover, the art was intimately tied to its urban site, to its diversity, anthropological patrimony, social actuality, and political contingency.16 Crispolti was one of the leading curators to organize Arte Ambientale exhibitions in Italy’s urban landscape, and his 1976 Venice Biennale exhibition, called Ambiente come Sociale (Environment as Social), solidified the term’s prevalence as he presented urban projects that sought to connect with the experience of the city.

Arte Ambientale artists developed an entirely novel way of working both in relation to each other and their subject matter, the city. A number of terms—both art historical and from the sociopolitical context—help bring definition to this practice. Arte Ambientale was closely tied to its sister-term arte nel sociale (art in the social sphere), which not only connoted art being made in the urban space, outside the traditional parameters of the gallery, but also stressed a social and interactive component.17 The term means art made “inside” the social context. Artworks were designed so that audiences

Figure 1.1 Ugo La Pietra, Segnali di fuoco, 1970, car tires, fire, performance, Zafferana, Italy.

Source: Image courtesy of the Artist © Ugo La Pietra

could interface with them; the experience of art was fundamentally active.18 This trend reflected not only an alteration in the role of viewers but also that of the artists; they were directly participating in the sociopolitical sphere and looking to insert their work within this context. This participation can be directly connected to the activism pervasive in the social sphere at the time. Likewise, another term was operatore culturale (cultural operator), expanding the definition of the artist’s practice to describe the work of the Arte Ambientale artist as active and functional within the broader sociocultural sphere. Their work, therefore, was not limited to a fine art denotation but rather could include a multidisciplinary approach and incorporate architecture, design, performance, theater, literature, and any manifestation of a humanistic expression. Lastly, the expression rete diffusa (diffused network)—associated with the sociopolitical sphere more than the arts—describes how Arte Ambientale artists, despite their geographical dispersal, were bound by ideas, which at times, like Zafferana, brought them together to collaborate on projects, all the while maintaining their distinct practices.

While Arte Ambientale drew on Italy’s specific sociopolitical context, commonalities can be cited with other concurrent art tendencies in Europe and the United States that can be broadly categorized as Land Art and Institutional Critique. Like many Land Art undertakings, Arte Ambientale projects were site-specific: conceived and created for that space. Furthermore, they were also temporary, installed for a limited time only, and now exist predominately in documentary form. Additionally, positioned outside, Arte Ambientale artworks inherently critiqued the spaces of aesthetic display of the art establishment, in both museums and galleries in ways that relate to many Institutional Critique initiatives. However, an important distinction must be made: Arte Ambientale defined art that was placed in dialogue with the urban territorio (territory), specifically.19 Enrico Crispolti noted that while Land Art had a romantic quality, in that it was primarily situated in the vast natural landscape, Arte Ambientale was intricately tied to the city.20

Nevertheless, the development of art in the urban environment was not limited to Italy. On the contrary, artists were creating what can be called Environmental Art during the 1970s in major cities in the West. For instance, American artist Gordon Matta-Clark had been making luminous incisions into dilapidated buildings since the late 1960s, drawing attention to questions of urban renewal and gentrification. Indeed, New York City’s shifting landscape was a fertile ground for such interventions, and artists like Charles Simonds created miniature, impermanent constructions in the nooks of already-existing buildings for what he called “Little People.” As early as 1965, Alan Sonfist began Time Landscape on the corner of Houston and La Guardia Place, where he reclaimed a wasteland lot and planted forest plants indigenous to Manhattan, effectively returning the landscape to a pre-urban space. Meanwhile, Richard Serra’s early-1970s work in the Bronx, To Encircle Base Plate Hexagon, Right Angles Inverted, can also be called Environmental Art. Contemporaneously in Europe, the Collectif d’Art Sociologique (Sociological Art Collective) in Paris explored art’s relationship with society by applying sociological methods—such as interrogative survey activities—to reach ordinary inhabitants and spur introspection about their daily lives. In the United Kingdom, artists like Stephan Willats and Graham Stevens were also working directly in the urban sphere.

However, recent scholarship on these initiatives in the 1970s, and the even later 1990s practices, notably the genealogy outlined by art historian Miwon Kwon on site-specific art, charts its emergence from the legacies of Minimalism, specifically an art based in an experiential understanding of physical attributes of the site, and Institutional Critique, where site also means a network of sociopolitical references.21 The development of Arte Ambientale in Italy, however, had a different origin, as Minimalism was not as dominant as Kinetic Art or Op Art in the 1960s. Artists laboring under the umbrella term Arte Programmata (Programmed art), which included groups like Gruppo ENNE, based in Padua, and Gruppo T, based in Milan, sought to break down perceptual schemas; blur the boundaries between art, architecture, and design; and conceive of artworks spatially and phenomenologically.22 Building on this legacy, and others, such as the Bauhaus, Art Informel, and Fluxus, Arte Ambientale artists further expanded the frontiers of site specificity outside the gallery and into the urban environment.

Their recasting of this shift as Institutional Critique, like their American contemporaries, was the result of understanding the conditions of production and the function of art within the art economies and art institutional sphere.23 In Italy specifically, the spirit of the 1968 social uprisings, the challenge to authoritarianism, and the prevalence of labor movements, both in action and in theory, cannot be underestimated. Arte Ambientale artists aligned themselves with the percolating countercultural sphere, and they viewed the art establishment—the interconnected system of museums and galleries—as insular and unsympathetic to projects that addressed social concerns. These artists all shared the desire to extricate themselves and function on their terms. They thus can be understood as distinct from the anti-political stance that characterized much of the art world’s mainstream galleries and institutions, as well as the artists that were supported within this sphere, like Luigi Ontani and Gino de Dominicis. Instead, Arte Ambientale artists chose to inhabit a peripheral position that challenged the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Figures

- List of Plates

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Extramural Exhibitions: Volterra ‘73 and Ambiente come Sociale

- 3 Redeployment of Sculpture in the City: Francesco Somaini and Mauro Staccioli

- 4 Riappropriazione Dell’Ambiente: Ugo La Pietra’s and Franco Summa’s Urban Interventions

- 5 Vox Populi: Franco Vaccari’s and Maurizio Nannucci’s Audience Engagement

- 6 Conclusion: The Legacy of Arte Ambientale

- Index