![]()

1 David Livingstone’s Invention of South Central Africa

Upon returning to England in December 1856 after 16 years in the interior of Southern Africa, David Livingstone,1 the celebrated missionary and explorer, received an enthusiastic welcome. Already a household name because of his well-publicized discoveries and travels, Livingstone now found himself a hero of national stature.2 The Royal Geographical Society and the London Missionary Society organized large receptions in his honor; he received the freedoms of several cities, including London, Edinburgh, and Glasgow; Oxford University awarded him an honorary D.C.L. (Doctor of Civil Law); and Queen Victoria invited him to a private audience (Schapera 1963, ix–x). Likewise, the encyclopedic narrative of his adventures, Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Livingstone 1857), garnered numerous favorable reviews, sold some 70,000 copies, and ultimately made the missionary a rich man.3 Livingstone’s narrative, wrote one early reviewer, opened up “a mystic and inscrutable continent,” while the story of Livingstone’s famous four-year transcontinental journey – the first such documented journey in history – inspired admiration for being “performed without the help of civilized associate, trusting only to the resources of his own gallant heart and to the protection of the missionary’s God” (“Dr. Livingstone’s African Researches” 1858, 107).4 In promoting the Zambesi River as a natural highway into the interior of Africa and in advocating for the three C’s – Christianity, commerce, and civilization – as a means to ending the slave trade and opening the continent’s natural riches to the outside world, Missionary Travels also struck a resounding chord with the public. Reviewers welcomed Livingstone’s pronouncements while describing the missionary as “an instrument, divinely appointed by Providence for the amelioration of the human race and the furtherance of God’s glory” (“Livingstone’s Missionary Travels” 1858, 74).

In the last 40 years, critics have advanced a variety of arguments to account for the surprising popularity of Livingstone and his narrative. Many of these arguments center on Victorian cultural factors or on the cumulative force of Livingstone’s biography, travels, and ideas. Patrick Brantlinger (1988, 180) singles out Livingstone’s iconic status as a “saintly bestower of light,” one whose ideas gave shape and direction to a growing Victorian cultural debate on the duty of Britain to Africa. Andrew Ross (2002) points to the publicity that preceded the Livingstone’s return to London, particularly the excitement generated by his discoveries and his arrival at Loanda (in present-day Angola) in 1854. William Cecil Northcott (1973, 50) argues that Livingstone as an individual “embodied all the ingredients of heroism that [Victorian Britain] idealized – rugged simplicity, a victory against odds, dedication to a cause, plus a patina of piety that stirred emotions,” while in his biography Tim Jeal (2013, 163) argues that “[t]here is no one reason that accounts for Livingstone’s sudden emergence as a national hero.” Rather, Jeal posits, factors as diverse as Livingstone’s ability to combine “patriotism and Christianity” (3), his transcontinental journey, and the fact that Livingstone’s ideas and life story appealed to the expanding middle class as well as the leaders of industry and commerce all contributed to the missionary’s fame and best-selling status (163–65). Finally, Dane Kennedy (2013, 246) cites “a distinct convergence of forces,” including Livingstone’s allure as a missionary to “the millions of devout Christians” in mid-Victorian society, “his antislavery message,” “the shrewd public relations campaign conducted by Sir Roderick Murchison, the president of the RGS,” and the simultaneous “emergence of a cheaper, freer, and more popular press, whose editors understood that celebrities sold newspapers” (Kennedy 2013, 46; cf. Ross 2002, 109–10; Pettitt 2007, 36)

Those critics that focus on the actual narrative of Missionary Travels as key to the success of both text and missionary likewise develop a variety of theories to support their claims. Mary Angela Schwer (1996, 194), for instance, argues for Livingstone’s careful self-fashioning, which “blended elements both of the Christian soldier tradition and of middle-class ‘muscular Christianity,’ with its concern for chivalry and hard physical work,” while Meriel Buxton (2001, 104) emphasizes Livingstone’s panoramic gaze and his descriptive abilities: “His catholic interest in everything around him enabled him to write sufficiently detailed descriptions to satisfy the scientist while simultaneously painting a vivid enough picture to enthrall the lay reader.” Timothy Holmes (1993) also cites the power of Livingstone’s descriptions but highlights the missionary’s overall editorial dexterity as key to generating mass appeal. Missionary Travels, Holmes observes, “contains […] something for everyone,” including Christians, missionaries, abolitionists, medical men, empire builders, mill owners, engineers, geographers, naturalists, and geologists (124). Felix Driver (1996, 122), while giving prominence to the role of institutions like the Royal Geographical Society and London Missionary Society in fostering Livingstone’s fame, adds that the missionary, like other mid-Victorian explorers, “created imaginative geographies” that offered “new ways of seeing the world beyond Europe.” “For Livingstone,” Driver concludes, “Central and East Africa was above all a landscape to be cultivated.” In one of the most intriguing recent studies, Justin Livingstone (2014, 71; also, see 69–113) moves away from “the quest to explain Livingstone’s popularity” altogether “and instead scrutinises the very nature of his heroic identity” while suggesting that the missionary was in fact “a suite of heroes of multiple identities produced out of a plurality of Victorian cultures.”

However, despite the vast ground covered by these readings, previous critical work has failed to address one key dimension of Livingstone’s project – the missionary’s ability to map the cultural and physical geography of Southern Africa in a way that responded to the sacred and secular desires of the British public. This chapter, in contrast, focuses on this aspect of the narrative by giving attention to the specific features that enabled Missionary Travels to be so effective as a public document. In doing so, the chapter draws on the published text to explore how Livingstone develops his “narrative of benign imperial influence” (De Kock 1996, 163) while imposing a series of imaginary overlapping boundaries on the heart of Southern Africa. The chapter argues that Livingstone casts the region – previously the subject of myth and uninformed speculation – into a “very inviting field” (Livingstone 1857, 508) for the capitalist and missionary alike. South Central Africa, as Livingstone shapes it, abounds with idyllic and “fertile” lands, with indigenous populations predisposed to the institution of Christianity (especially the Makololo ethnic group), and with self-motivated individuals longing for the introduction of commerce. Through such representations, Missionary Travels thus develops, suitably populates, and so overdetermines an ideal, interstitial site for British colonial intervention. Sustained analysis of the contours of this representation, in turn, helps illuminate broader British strategies of expeditionary discourse production during this historical moment. In its overall approach, the present chapter also provides a bridge between previous Eurocentric criticism on Victorian expeditionary literature and the intercultural methodologies that this monograph will advance in subsequent chapters – methodologies that foreground the role of non-western forces and agencies in predetermining or otherwise shaping expeditionary discourse production.

* * *

Livingstone’s cartographical success depends, foremost, on his ability to develop a seemingly respectable and transparent narrative persona. His prose, Leon de Kock (1996, 166) observes, “deliberately underplays individual glory while maintaining the empirically impersonal rhetorical posture appropriate to the observing scientist.” Key to this project is Livingstone’s lower-middle-class background. In the opening pages of Missionary Travels, Livingstone details his arduous childhood, which included 14-hour workdays and extended night-time study sessions, and notes his own skill in combining manual work and intellectual endeavor: “My reading while at work was carried on by placing the book on a portion of the spinning-jenny, so that I could catch sentence after sentence as I passed at my work” (1857, 5–6). Likewise, he underscores the formative value of his childhood: “Were it possible, I should like to begin life over again in the same lowly style, and to pass through the same hardy training” (6). Such pronouncements showcase Livingstone’s humility, while also linking him to an assortment of nineteenth-century Nonconformist missionaries, “men who had made their way from laboring, peasant, and artisan backgrounds to the lower reaches of the bourgeoisie” and so were “marked by modest upward mobility and the acquisition of respectability” (Comaroff and Comaroff 1991, 1:80–81). At the same time, Livingstone’s personal triumph over adversity, his arduous rites of passage, and his impressive Protestant work ethic position him as a paragon of individual comportment and set his life as a model for the ideal missionary career path, a fact well-noted by organizations such as the London Missionary Society, one of Livingstone’s primary sponsors during his first stint in Africa (A. Johnston 2005, 36–37).

Livingstone’s religious ethic also contributes to rendering his persona credible. Throughout Missionary Travels, Livingstone emphasizes his honesty, a virtue rooted in his Christian upbringing. This honesty both connects him to the piety of his Scottish ancestors (Livingstone 1857, 2) and becomes one of his primary strategies for working with Southern Africa’s indigenous populations: “the truthful way of dealing with the uncivilized is unquestionably the best” (274). Livingstone’s apparent honesty also infuses an important element of transparency into his story, a point not lost on his early reviewers who praise Livingstone for such qualities as his “candor” (Abraham 1858, 178) and “manly truthfulness” (Dickens 1858, 124). In addition, Livingstone aligns his own humble work with a larger Providential plan. In the final pages of Missionary Travels, for example, Livingstone casts his ostensibly “formless” narrative (“Livingstone’s Travels in South Africa” 1857, 1422) into a radical new configuration by revealing, deus ex machina, that the “Divine hand” has determined the overall course of his travels and adventures (Livingstone 1857, 678). Through this move, Livingstone recuperates the scenes of toil, suffering, and illness that pervade Missionary Travels and establishes what Victorian religious enthusiasts would soon call his “muscular Christianity” (see Schwer 1996, passim). Livingstone’s narrative as a whole thus acquires an unexpected moral urgency, suggesting that he offers his colonial directives based on his own firsthand experience and because he has received a higher calling.

Yet it also bears noting that Livingstone’s seemingly transparent persona masks an overarching project of self-aggrandizement. In an oft-quoted letter to his sisters Janet and Agnes Livingston[e] of 30 Mar. 1841, Livingstone (1959, 1:31) writes that he “would never build on another man’s foundation,” revealing an independent and headstrong spirit. This spirit resurfaces in many passages in Missionary Travels, even if in a somewhat random fashion. For example, in describing his relations with the Makololo, Livingstone notes his skill in maintaining the devotion of the group via displays of his own independence and resilience (1857, 353–54) and stresses his ability to discipline his attendants:

I seized a double-barreled pistol, and darted forth from the domicile, looking, I suppose, so savage as to put them to a precipitate flight. As some remained within hearing, I told them that I must maintain discipline, though at the expense of some of their limbs; so long as we traveled together they must remember that I was master, and not they.

(347, emphasis added)

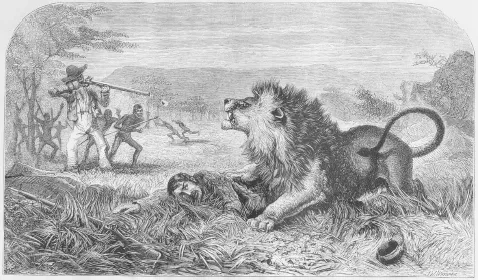

Several famous incidents, most notably the near-death encounter with the lion (11–13), also point to Livingstone’s interest in self-aggrandizement.

The lion incident, an encounter in which Livingstone barely escaped being mauled and which rendered his left arm permanently disabled, has been key in fostering the Livingstone myth (Figure 1.1). Nearly all early reviewers celebrate the incident, while one even argues that there is “no doubt it is perfectly authentic” (Abraham 1858, 174). However, the evidence of Livingstone’s letters tells another story. The “unwitting and unwilling participant” of the earlier manuscripts, Mary Angela Schwer (1996, 210–11) observes, becomes “a natural gentleman” in Missionary Travels, one that demonstrates “how a true manly spirit could conquer and thrive” in Africa.5 Comparison of the journals and letters with Missionary Travels reveals further instances of such revision (see Schwer 1996, 207–33; Schapera 1963, xv–xix). “Whatever [Livingstone] says in [Missionary Travels],” writes Isaac Schapera, “must be checked with his journals and letters, and in case of discrepancy the version finally published needs to be treated with more caution than biographers and historians have normally been in the habit of showing” (Schapera 1963, xviii; cf. Livingstone and Wisnicki 2019) Livingstone’s textual persona thus emerges as a strategic creation, one that the missionary6 carefully cultivated in developing the final narrative of Missionary Travels.7

Figure 1.1 “The Missionary’s Escape from the Lion.” Illustration by Joseph Wolf from Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857, opposite 13).

* * *

In Missionary Travels, Livingstone also builds up his credibility by drawing on his extensive fieldwork or, as the narrative’s subtitle puts it, “sixteen years’ residence in the interior of Africa” to support his claims. Livingstone’s extended immersion allows him to offer comprehensive and ostensibly definitive representations of Southern Africa and its inhabitants. Textual catalogues, scientific expositions, detailed maps, an appendix of latitudes and longitudes, and set pieces that encompass the microscopic (e.g., the Tsetse fly (Livingstone 1857, 80–83)), the macroscopic (the Kalahari desert (47–52)), and the intermediate (the lion (136–42)) all underscore the magnitude and depth of the missionary’s gaze.8 Livingstone’s observations culminate in his grand theory of the Central African basin, a theory that, he states, accounts for “the true form of the river systems and continent” (473, but see 473–79). The theory, in its all-encompassing scope, allows Livingstone to apprehend the geological history of the entire southern portion of Africa (473) and, significantly, to present this knowledge to his readers through his narrative.9 Of course, as noted in the narrative’s dedication, Livingstone is a bit late in formulating his theory:

To Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, President Royal Geographical Society […] to express admiration of his eminent scientific attainments, nowhere more strongly evidenced than by the striking hypothesis respecting the physical conformation of the African continent, promulgated in his Presidential Address to the Royal Geographical Society in 1852, and verified three years afterward by the Author of these Travels.

([iii])

However, despite his belatedness, Livingstone (as the text indicates) still manages to assign himself credit for having “verified” Murchison’s theory and so succeeds in marshaling even the RGS president in the service of his, Livingstone’s, own statements.

As an explorer and missionary, Livingstone’s travels place him in what Mary Louise Pratt calls the “contact zone”: the “social [space] where disparate cultures m...