![]()

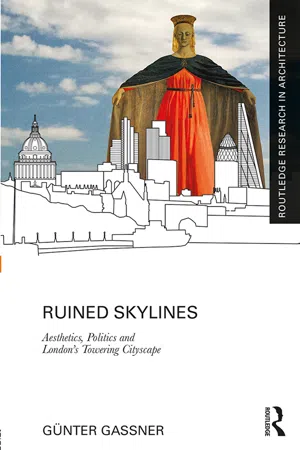

1 Conservative representations

This book is the result of a twofold critique: first, a critique of the construction of more and more commercial towers in London; and second, a critique of the idea that these towers ruin London’s historic cityscape. One of the key problems with the current tall-building boom, as I see it, is that both professionals who argue for and those who argue against the construction of towers in the City of London (hereafter the City) reduce the city to an easily marketable visual representation. This reduction is not always immediately apparent; especially not in the criticism that some historians put forward when a new tower is being proposed. Yet, the concepts that are developed and the instruments that are used do exactly that: they further commodify the city and turn the city into an ‘image’ that has the main aim of attracting global investment and revenue-generating tourists. The basic premise of visual commodification, as we will see, is the idea of a well-arranged city. The widespread idea that the construction of additional skyscrapers ruins the historic cityscape is based on the same premise of an orderly city. It assumes, I will argue, an element of integrity that is ideological and which itself must be ruined in order to open up a space for politics.

We need radical interventions in urbanisation processes under financialised capitalism – perhaps more now than ever before. Attempts to visually protect the cityscape or individual historical buildings in the city do not open up a space for radical politics that can bring about social change. They foreclose or, at the very least, narrow such a space, which, in turn, expedites London’s tall-building boom. They draw attention away from the fact that contemporary London is largely built by globally operating investors and private real estate developers with a state that acts as a hands-off manager. However, whose city is a city where the primary aim is to attract more and more investors and developers? Whose city is a city in which planning processes, which are negotiations between developers and planning authorities, are developer-driven? Whose city is a city in which, in these processes, almost nothing seems to be non-negotiable, that is, everything seems to be measurable and reducible to aspects of profitability and economic viability? Whose city is a city in which investment flows to urban areas and industries where the rate of return is highest and not to the least advantaged areas? Whose city is a city in which the production and utilisation of surplus capital are left in the hands of a few?1

In this book I suggest that, in order to politically intervene in today’s urbanisation processes and London’s development trajectory, we need political images. Put differently, we need images that engage with and counter those conservative representations that have occupied city-making for decades. The old slogan that ‘There is No Alternative’ to a market-driven society has never been innocently based on the idea that one might not like a ruling free market but one has to simply accept it. The market economy has rarely been seen merely as one of many aspects of society that works in itself and, therefore, requires no intervention from outside. Rather, and more fundamentally, as we can see in Margaret Thatcher’s case, political freedom was equated with economic freedom. And even though the old neoliberal ideology that one must not govern despite the market but for the market – the idea that we need a slightly freer society with fewer restrictions in order not to redistribute wealth but to create more and more wealth – has, as many argue, clearly been proven wrong, this has not produced political images.2 We need, I argue in this book, images that are political because they intervene in a traditional and nowadays market-serving sense of visual order and rightness of the city. We need images that precisely do not equate political freedom with economic freedom.

When I refer to images I do not mean visual representations of what the city looks like. I also do not mean mental images or normative representations of what the city ought to look like. The point of political images is not to depict a visual alternative, and, in so doing, to provide another representation for the visual commodification of the city. Rather, the point is to develop images that are political because of their visuality. These images are political because they disrupt or destabilise the way in which the city is sensed and made sense of. They are political because they inaugurate something new. They are political not because they represent an action but because they act.

To be sure, visual images of the city are always political in the sense that they are inscribed in power relations. They are political because they are controlled by the state or an elite. But the images that the city needs, I suggest, are images that are fundamentally linked to change. Hence, if vision can be understood as an act of perception and as an act of imagination, then we need to add the act of making changes to the status quo.3 Political images are about perception, imagination, and change. And these are three dimensions and not three aspects that are linked in a causal chain. Seeing the city, imagining a city, changing the city: this is not simply a linear process according to which seeing the city and imagining a different city lead to changes to the city; such a process can be – and is currently – easily co-opted by market interests. The images that I have in mind are political because they change what we perceive in the city and how we imagine the city. They are political because they allow us to imagine multiple perceptions and different changes. They are political because with and through them we are capable of perceiving imaginations and changes.

These political images have in common with Cornelius Castoriadis’ account of ‘creative imaginary’ that they are in tension with the ‘tightening grip of the capitalist imaginary’.4 As Ben Campkin shows in Remaking London, the creative imaginary refers to ‘the tools of autonomous individuals in achieving change and resistance to capitalist domination’.5 With regard to a tall-building boom, however, what is the political relevance of individual resistance? City-making is a collective undertaking with a collective that is defined by different perceptions and different imaginations of the city. The most useful images, then, are images that bring differences together or, more precisely, that relate differences to each other. And perhaps these are images that do not resist but that result from capitalist urbanisation, while at the same time or, better, as a result of which they work against capitalist domination. What interests me in particular is to see how these political images that operate from within are linked to a tall-building boom.

In this book I want to discuss how the relationship between the visual and the political is related to socio-economic change or, to put this differently, how visual change links to a fundamental urban transformation. Hence, my key focus is less on a detailed analysis of what might be called the politics of aesthetics, by which I refer to the multiple different ways in which a certain appearance results from and consolidates existing power relations. I am specifically interested in the aesthetic dimension that is inherent in radical politics. Theorists, such as Hannah Arendt, Jacques Rancière, and Walter Benjamin, identified and described this dimension and, as we will see, their accounts differ in terms of their understanding of both politics and aesthetics. Still, for none of them could politics be reduced to institutional politics, and for none of them could aesthetics be reduced to matters of art and beauty. In their distinct ways, they explored questions of perception, imagination, and change, and they emphasised that making sense of the world and acting in the world require aesthetic forms; that aesthetic forms and aesthetic judgements introduce something new into the world and that they are, therefore, linked to radical politics. Hence, if we read the city as a ‘work of art’ in the sense that cityscapes can be understood as ‘legible documents that can tell us something about the values and aspirations of their rulers, designers, buildings, owners and inhabitants’, then we need to be careful not to deprive aesthetics and, above all, the visual of its political agency.6 Precisely because cities respond ‘to the aspirations of its dominant classes with institutions and built environments to serve their interests and reinforce their values’, as Donald J. Olsen proposes, it is important to explore not only the ways in which the city changes visually but also the ways in which the visual can bring about an urban transformation. This is not a question about politicising the visual; it is about nothing more than drawing out the visual dimension of politics.

If the cityscape is political in that it is the result of existing power relations and ways of sensing and make sense of the city, how, then, is it political in the sense that it disrupts the status quo and brings about change? In this book I explore this question through the lens of a city’s skylines and, in particular, in relation to what I call the new London skyline: the ways in which proposed office towers in the City are being framed, explored, and explained in urbanisation processes and in planning debates especially.

A tall-building boom

Has London’s tall-building boom introduced a new visual order in the city? In this book I will show that it has not. And, yet, there are more than 400 skyscrapers currently in the pipeline (that is, they are either proposed, approved, or already under construction).7 Eighty per cent of them are residential towers – a number that is particularly important given the shortage of affordable housing in London. Yet, the large majority of these residential towers accommodate luxury apartments that offer great views across the city. The additional supply of housing that London will see in the years ahead will not make living in London more affordable.

A group of mostly architects and artists who have organised against the tall-building boom under the so-called Skyline Campaign – a campaign that aims to stop the devastation of London by badly designed and poorly placed tall buildings – claims that many of these luxury flats are nothing other than investment opportunities for wealthy people from all over the world to ‘park’ their money in London and that many of them will simply be left unoccupied before they are resold. Residential towers are also an opportunity for the Mayor of London, campaigners suggest, to show that he can attract investment and tackle the housing shortage – even though the problem of unaffordable housing is not being addressed – and for local councils to gain extra revenue in order to fill the holes left by the economic recession after the 2008 financial crisis. These are important points to consider. It is for good reason that David Madden and Peter Marcuse argue for ‘the creation of an alternative residential logic’ and for a model that constructs dwellings for cooperative and social housing.8 But does this mean that, in order to tackle the current housings crisis, ‘vertical social housing must rise again’, as Stephen Graham suggests?9 After all, many studies of the relationship between density and urban form, including those of the Urban Task Force – a research group led by Richard Rogers – have shown that high residential densities can be achieved with medium-rise buildings.10 Nevertheless, Graham’s point that, as the architecture critic Owen Hatherley has remarked, social housing projects from the 1930s up to the 1970s ‘continue to be useful: a potential index of ideas, successful or failed, tired, untried or broken on the wheel of the market or the state’ is, of course, important.11 ‘Even in their ruinous state’, Hatherley suggests – and I would also argue because of their ruinous state – ‘they can still offer a sense of possibility which decades of being told that “There is No Alternative” has almost beaten out of us’.12

London’s residential tower boom exemplifies significant processes that define urbanisation nowadays. The first is commodification. While commodific...