eBook - ePub

East Asian Art History in a Transnational Context

This is a test

- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

East Asian Art History in a Transnational Context

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is the first comprehensive English-language study of East Asian art history in a transnational context, and challenges the existing geographic, temporal, and generic paradigms that currently frame the art history of East Asia. This pioneering study proposes an important new framework that focuses on the relationship between China, Japan, and Korea. By reconsidering existing concepts of 'East Asia', and examining the porousness of boundaries in East Asian art history, the study proposes a new model for understanding trans-local artistic production – in particular the mechanics of interactions – at the turn of the 20th century.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access East Asian Art History in a Transnational Context by Eriko Tomizawa-Kay, Toshio Watanabe, Eriko Tomizawa-Kay, Toshio Watanabe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Asian Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

Constructing the Idea of East Asian Art

1 Reconsidering the History of East Asian Painting

Painting from China vs. Chinese-style Painting in Japan

Shimao Arata

Introduction

It goes without saying that a wide variety of issues, both theoretical and practical, are embedded in the question at the core of this volume, namely, is 'East Asian Art History' possible? In the field of Japanese history, an 'East Asian perspective' has been advocated for some time, but what seems to have started with the relatively simple idea of looking more broadly at the relationships between Japan, China, and Korea has, in current discourse, having faced the tide of postmodernism, become rife with complexity and even contradiction.

The current view of the issue originated in the critique of discourses founded on histories based in the narratives of individual countries defined by national borders and the illusion of the nation-state. Consequently, it has become necessary to think in terms of a more dynamic model of cultural domains that have ambiguous borders and that expand and contract even as their peoples intermingle. If we are to apply this theory consistently, the only way to talk about these various overlapping, interconnected regions of the world is in terms of a 'Global History'.

On the other hand, the false conception that modern learning itself has the capacity to systematically describe various spheres of human activity has fallen away, while at the same time the self-righteousness of macrohistories that look down on the world from the perspective of a god-like figure is also being criticized. If we take this concept still further, it becomes clear that any theory or method of historical description is no more than a single paradigm. Even setting aside this idea momentarily, there is no way that we can deny cultural pluralism and the microhistories that document defined territories in detail. Indeed, sorting out the theoretical relationship between the part and the whole, and popularising such a method of research, are not simple matters.

There are various different arguments for an East Asian art history, but ultimately we must look at the region not in terms of the three 'countries' of China, Korea, and Japan as discrete elements, but rather must view the whole as a single organic system. In this essay, I would like to examine the example of Muromachi-era kara-e—literally, 'Tang pictures'—as a case study for considering the issues at play in such an approach.

'Chinese Paintings' and the Higashiyama Gomotsu Treasures

The challenges in thinking about a history of East Asian painting are clearly apparent in my own field of specialization, art of the Muromachi period (15th—16th centuries). As is widely known, Chinese paintings from the Southern Song to Yuan dynasties entered Japan in large numbers during the Kamakura and Nanbokuchō periods (13th—14th centuries). In the Muromachi period, major works were brought under the control of the most powerful men of the day, the Ashikaga shoguns, who worked out various systems for display and organization of their collections. Thus, in one sense, these works from China took on a leading role in Japanese art circles and at the same time gradually came to set the standard for Japanese painters. As a result, they have come to be viewed in two separate contexts, that of Chinese painting history and that of Japanese painting history. Unsurprisingly, differences arise between the two viewpoints.

These differences have been exemplified in past exhibitions that have featured these paintings. For example, Itakura Masaaki, author of one of the essays in this volume, organized two exhibitions: Southern Song Fainting: Elegant and Noble in Soul at the Nezu Museum in Tokyo in 2004, and Aesthetic Perfection: The Higashiyama Gomotsu Collection Assembled by the Ashikaga Shoguns in the 14th to 15th Centuries at the Mitsui Memorial Museum in Tokyo in 2014. In the former, Southern Song paintings in Japanese collections were clearly presented as Chinese paintings, while in the latter, the emphasis was placed on the context in which the artworks were collected, displayed, and seen in Japan as a part of a category of Chinese-style paintings known as kara-e. As demonstrated in the very wording of the titles of the two exhibitions, the same Chinese paintings could be understood from two distinct angles—that is, as either Chinese or Japanese—through the choice of the term 'Southern Song Painting' or the name 'Higashiyama Gomotsu' (as the Ashikaga shogunal collection was known). Formation of a broader East Asian painting history is not necessarily as simple as joining these two together, however. First, let us examine the situation from the Japanese perspective.

The Three Chinas

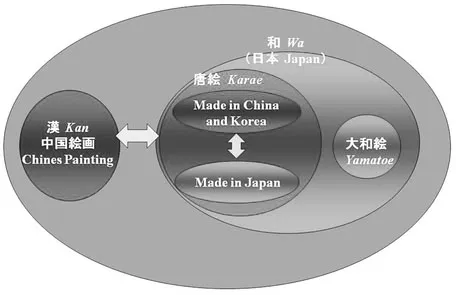

In the Muromachi period, both Chinese paintings that had come to Japan and Japanese paintings produced to emulate them were known by the same term, kara-e. These existed in contradistinction to Japanese-style paintings known as yamato-e, and China itself was of course external to both of these types (Figure 1.1). In short, a framework had come into existence comprised of: (a) Chinese-produced kara-e and Japanese-produced kara-e internal to Japan, and (b) China itself and other Chinese paintings external to Japan. To better understand this situation, we need to further expand our thinking to account for three Chinas: (1) the world of Chinese painting external to Japan, (2) the world of Chinese painting that was brought to and developed within Japan, and (3) the world of Chinese-style paintings that were produced in Japan.

Once we merge the latter two together as kara-e, we are able to look at this situation in two different ways. One is the conventional view of Chinese painting vs. Japanese painting, and the other is Chinese painting vs. kara-e. Taken literally, kara refers to China as a physical place, but in the case of kara-e, it no longer indicates the geographic place of origin of these paintings. In a sense, the term kara-e, which encompasses paintings that were made in both China and Japan, represents the very embodiment of the concept of 'deconstructing boundaries' that was at the heart of the symposium (SOAS, London, 2015) that inspired this publication. I believe that thinking in terms of dualities of meaning—or perhaps even a semi-lattice kind of relationship—involving the 'local' and 'global' is essential to the consideration of a history of East Asian painting. For example, as Itakura Masaaki's study of the perspective taken by the Ming-dynasty literati painter Jin Shi from Ningbo demonstrates, we are beginning to see discussions of local perceptions of East Asia as a broader entity.1 To clarify this argument, I would now like to reexamine the basic definition of kara-e.

Figure 1.1 Framework of Kara-e, Yamato-e, and Chinese painting

It goes without saying that the Chinese paintings that made their way to Japan represented a small fraction of what existed in China itself. The Gomotsu on'e mokuroku (Catalogue of the masterworks in the shogunal collection), starting from the time of the third Kamakura shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408) onward, lists about 300 paintings, most of them by just thirty Song- and Yuan-dynasty Chinese painters.2 Although these thirty individuals were not the only Chinese painters whose artworks had been brought to Japan at the time, the total, including those not listed here, was still probably only around fifty major artists.

The Kundaikan sōchō ki (Manual of the attendant of the shogunal collection) provides a list of about 150 names of Chinese painters that was produced in consultation with the Yuan-dynasty painting history Tuhui baojian (Precious mirror of painting). It included the names of painters such as Li Cheng and Guo Xi, whose paintings had never been seen but whose names were known from Chinese painting histories, literature, or other written sources.3 As Shih Shou-chien has pointed out, this transmission of kara-e through text was also significant, and by this time had enabled an image of Chinese painters external to Japan, including some who were 'yet unseen'.4

As for the situation in China itself, Tuhui baojian names 1,500 painters, starting with Cao Buxing of the Wu dynasty and continuing through the Yuan dynasty. One thousand names appear from the Song and Yuan dynasties alone. This is just one example of a written source, but even a rough calculation shows China having fifty times the number of painters listed in the Gomotsu on'e mokuroku, and ten times the number cited in the Kundaikan sōchō ki.

The difference between Chinese paintings and kara-e produced in China does not stop at such quantitative measurements. It is true that the works recorded in the Gomotsu on'e mokuroku were a subset of Chinese painting, but if we look at them in terms of cultural history, they do not seem to reflect the general state of painting in mainland China.

For one, there are differences in the range of artists and the numbers of paintings they produced. For example, in terms of the number of paintings, Japanese records document more than one hundred paintings by the Southern Song Zen painter Muqi; he is followed by the Southern Song court painter Liang Kai, with just under thirty paintings. Flowever, Muqi was not a major figure in mainstream painting histories in China and, though he was well known, Liang Kai was not particularly exceptional among the imperial painters of his day. Their dominance in Japan, on the other hand, reflects the unique circumstances of transmission resulting from the fact that it was primarily Zen monks who were bringing the paintings from China to Japan. Muqi was a disciple of the Chinese high priest Wuzhun Shifan, who was also popular among Japanese Zen monks, and although he was an imperial painter, Liang Kai also produced many monochromatic Zen-style ink paintings and had close personal associations with Zen monks. Such factors increased their local popularity within Japan.

Kara-e and Chinese Paintings

Knowing this, if we take an additional look at the artists mentioned in the Gomotsu on'e mokuroku, we see notable figures such as Emperor Huizong and Li Gonglin of the Northern Song dynasty or the academic painters Ma Yuan and Xia Gui of the Southern Song dynasty (who were famous in China as well), but we also find the names of Buddhist painters, such as Zhang Sigong, or Zen- and Buddhist-style painters, such as Yuehu and Men Wuguan, who do not appear in Chinese official painting histories. The latter artists most certainly entered Japan in the context of Zen Buddhism, and with some of them it is questionable whether their names were recorded correctly or even if they actually existed at all. However, it is evident that certain individuals whose names have not survived in Chinese painting histories have been preserved in the kara-e tra...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Color Plates

- Notes on Contributors

- Notes on Translations and Names

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I Constructing the Idea of East Asian Art

- PART II New Ways of Looking at Others

- PART III Translation of Art within East Asia

- Glossary

- Index