![]()

One of the main tensions that structured historical thought from the eighteenth century onward was that between the universal and the particular. Many scholars in history, philology, and philosophy accepted the Herderian insight that every historical culture is to be viewed as an “individual”—unique, unrepeatable, and centered around values and experiences that may be drastically different from those embraced at present. However, this theme was rarely taken to imply historical relativism. “Individualism” about historical cultures was usually accompanied by a general commitment to the main tenets of “universal history,” that is, to the idea that the history of humankind is a unified process with a general spiritual meaning.

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) himself rejects abstract forms of universalism that detach universal norms from feelings and concrete historical forms of life. He also criticizes the conception of linear historical progress. In his view, the idea that different historical cultures can be ranked hierarchically expresses a self-serving triumphalism that uncritically projects present-day standards onto the past. But while Herder’s recognition of radical “historical difference” may seem to pull in the direction of relativism, Herder also maintains that his pluralist vision of historical cultures is compatible with universalism. He articulates his universalism both in reflections on a common human nature and on history as the realization of God’s plan in the world.

Although Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s (1770–1831) systematic speculative philosophy may seem diametrically opposed to Herder’s multi-faceted and often meandering reflections, Hegel’s philosophy of history, too, is shaped by the struggle to reconcile the particular and the universal. Like Herder, Hegel is seeking to show how the seemingly abstract norms of reason acquire concrete forms in the historical process. In order to accomplish this task, he reconceptualizes the tension between the universal and the particular in terms of a relation of expression that pertains between the absolute and the relative. In Hegel, the ever-changing Volksgeist (national spirit) is the relative expression of the Weltgeist (world-spirit), which, in turn, is the historical manifestation of the absolute spirit’s movement toward self-consciousness. Of course, Hegel thinks of this process in progressive terms: history has a general meaning, because the “stages” of historical development are also the “stages” of the self-development of spirit toward freedom, self-consciousness and self-identity.

The professionalization of history as a Wissenschaft in the early nineteenth century went hand in hand with staunch opposition to this “speculative approach.” From Leopold Ranke (1795–1886) to Johann Gustav Droysen (1808–1884) and Jacob Burckhardt (1818–1897), historians were united in rejecting what to them seemed like a schematic apriorism that distorted history in order to derive quick philosophical generalizations. Even though most historians did accept that there was a universal history of humankind, they thought that knowledge of this universal history had to emerge as a hard-won result of the rigorous application of source criticism, the meticulous collection of particular facts, and the judicious compilation of individual national histories.

With this newly forming methodological awareness, the question of how to bridge the gap between the present and “historical others” received a new urgency as well. Although formulated in terms of relativism only rarely, understanding the past came to be viewed increasingly as a problem: too vast seemed the plurality of historical cultures, too great the divides between them. Finding solutions to this problem was one of the central strands that united the hermeneutic tradition and thinkers as diverse as Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), Droysen, Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911) and Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002). In Herder, it is primarily the commonality of human nature that allows for the possibility of understanding “historical others.” Schleiermacher places a stronger emphasis on the methodological process that moves between the particular and the general, the part and the whole, thus allowing one to approach—yet never fully reach—an understanding of past linguistic expressions. Dilthey combines both Herderian and Schleiermacherian arguments, and in his later work he uncovers inter-subjective understanding as the epistemological basis not just of textual criticism and history, but of all the Geisteswissenschaften. A slightly different solution to the problem of understanding can be found in Droysen and Gadamer, who seek the basis for historical understanding not primarily in human commonalities, or in a methodological process that mediates between part and whole, but rather in historical continuity and tradition.

The methodological discussions in history, philology, and hermeneutics were not without repercussions for philosophy. Toward the late nineteenth century, philosophers began to warn of “historicism,” which they considered tantamount to relativism and nihilism. Neo-Kantian philosophers such as Wilhelm Windelband (1848–1915) and Heinrich Rickert (1863–1936) and also historically minded thinkers like Dilthey, and Ernst Troeltsch (1865–1923) worried that the thorough historicization of all life and culture would undermine universal and necessary values. An additional problem emerged from the historicization of philosophy itself: as philosophers jettisoned the Hegelian assumption that the historical development of philosophy expressed a systematic schema, they began to worry that philosophical truths, too, might be relative to historical time, nationality, and culture.

The resulting discussions concerning the historicity of values and philosophical knowledge often intersected with debates over Weltanschauung. Philosophers wanted to maintain a role for themselves in adjudicating the conflicts between “materialistic,” “positivist,” religious, and “historicist” worldviews. Historical plurality came to stand in for political plurality. When Troeltsch worries that historicism leads to the “anarchy of values,” he does so in a situation in which the “historicization” of philosophy and theology has seemingly rendered these disciplines incapable of defending a consistent and convincing worldview. And yet, many held out hope that history would not just create a problem of relativism, but also hold the key to its solution. As Dilthey famously put it, the hope was that “the knife of historical relativism … which has cut to pieces all metaphysics and religion” would also “bring about healing.”

The contributions of this section explore the relations among history, philosophy, and relativism, as they unfolded from the late eighteenth to the mid twentieth century. Niels Wildschut analyzes the theological foundations of the historical thought of Herder and Ranke. He argues that it is only within their theology of history that Herder and Ranke appreciate the historical, individual, and diverse. But at the same time, their theology of history ensures that Herder and Ranke approach history from a monist starting point and with the intent to establish the ultimate harmony of history.

Katherina Kinzel focuses on how Windelband and Dilthey responded to the historicization of philosophy. She traces how both philosophers sought to fend off historical relativism by defending the idea of an ahistorical and permanent stratum of philosophical thinking. Kinzel shows, however, that this strategy was a failure: although they succeeded in blocking historical versions of relativism, both authors did so at the cost of incurring a relativism vis-à-vis philosophical systems.

Kristin Gjesdal revisits Gadamer’s reception of the hermeneutic tradition. She analyzes Gadamer’s suggested response to what he conceived as the historicist and relativist shortcomings of hermeneutics. Gadamer’s alternative approach views the existence of a continuous tradition as fundamental to our self-understanding as well as our understanding of others. Gjesdal criticizes Gadamer’s concept of tradition and contrasts it with Herder’s more self-critical approach to historical understanding.

![]()

Introduction

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) and Leopold Ranke (1795–1886) are often considered to be among the founding fathers of the tradition of German historicism. Authors like Wilhelm Dilthey (1901), Friedrich Meinecke (1936), and Georg Iggers (1968) have identified in Herder and Ranke’s thought central ideas that connect them to later historicist positions. For example, for both authors, historical phenomena have intrinsic value due to their individuality; the good in the human-historical world is necessarily plural; strong normative implications attach to diversity; and while all values depend on broad historical processes, it is necessarily illegitimate and suspect to endeavor to determine a priori standards of truth and historical progress. The historicist interpretation generally concludes that, because of these claims, Herder and Ranke must have been committed to historical relativism.

In this chapter, I explain why this conclusion is incorrect. Crucial to my argument is Herder and Ranke’s “theology of history” (Löwith 1949). In the literature defending historicist interpretations, its systematic importance has not been properly documented. I claim that it was only within their theology of history that Herder and Ranke appreciated the historical, individual, and diverse.1 Their theology of history ensured that Herder and Ranke approached the diverse and particular from a monist starting point and with the intent to point out the ultimate harmony of history.

In the first two sections, I start from the theological foundations that Herder and Ranke took to confer upon history its intrinsic value and existential significance. In the third section, I sketch how they sought to order historical material in larger harmonious wholes with the aim of providing a structure for universal history. In this way, I aim to establish that Herder and Ranke were not guilty of some of the crudest versions of the “problem of relativism” or the “crisis of historicism.” In the final section, I explore in more detail the views of Herder and Ranke on themes that are often considered relativistic. It is indeed remarkable how many of the relativistic themes identified by Maria Baghramian (in the history of philosophy) and Martin Kusch (in contemporary debates) seem present in Herder and Ranke (Baghramian 2004, 50–82; Kusch 2016, 107–108).2 Nevertheless, I aim to show that even regarding these themes, the positions of Herder and Ranke strongly diverged from later historicist positions. I conclude that Herder and Ranke should not be interpreted as relativists.3

Herder on revelation, history, and faith

Herder’s This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity: Contribution to the Many Contributions of the Century (hereafter TTPH) was published in 1774 (PW 272–358). This short treatise, with its fierce polemic against contemporaneous philosophy of history,4 has often been considered a foundational text of German historicism (e.g., Beiser 2011, 132). In the same year, Herder published two other works, both of a theological character: a collection of letters, An Prediger (To Preachers) and an exegesis of the Old Testament, Älteste Urkunde des Menschengeschlechts (Oldest Document of the Human Race) (FHA 9/1, 67–138, FHA 5, 179–660; Menze 2000, 11). In the latter, Herder puts forward the thesis that an original revelation pervades all of creation. The former presents religious faith as a universal psychological capacity and as part of the human condition. Taken together, these texts provide the foundation on which Herder relied in his 1774 attempt at presenting a unified vision of universal history.

In TTPH, Herder confronts the epistemological difficulties relating to this attempt (FHA 4, 32–42, 81–89). Furthermore, he relentlessly criticizes the tendency of his Enlightenment contemporaries to see their own historical standpoints as absolutely privileged and to consider their value-terms as universal tools fit for measuring historical progress.5 In order to properly assess this intervention by Herder into eighteenth-century philosophy of history, it is crucial to also take into sufficient account his own alternative to a one-sided progressivism. Herder’s alternative is a providential model according to which history is unified as one development. Herder claims that this development should be understood “in a higher sense than people have imagined it,” and that it is extremely difficult to pin down (PW 298, FHA 4, 41).6 Nonetheless, he is confident that history will appear as “God’s course through the nations”7 once it is approached from the right perspective (PW 349, FHA 4, 88). For Herder, identifying this perspective is a religious task. In this section, I show how Herder’s philosophy of history builds on his theology.

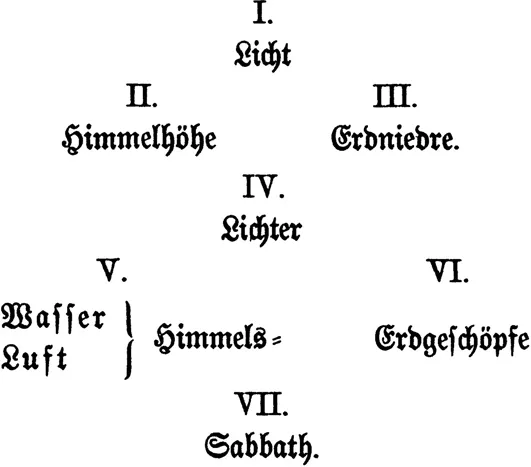

In Älteste Urkunde, Herder puts forward the thesis that God is omnipresent in nature and history (FHA 5, 298). Accordingly, he understands positive religions as ways of capturing a primordial revelation from different historical or geographical standpoints (305 ff.; cf. Gaier 1988, 73–74). This revelation is connected to God’s act of creation and handed down to humanity in the form of what Herder calls the Schöpfungshieroglyphe (hieroglyph of creation). According to Herder, this hieroglyph is God’s primordial revelation to humanity in a seven-step symbol or Denkbild (FHA 5, 281; cf. Häfner 1995, 216–221). This Denkbild communicates God’s act of creation in a form that prefigures the first written religious documents (FHA 5, 267–282). The hieroglyph structures the seven days of creation in the following way (see fig. 1).

The first book of Genesis is the paradigmatic example of how this Denkbild is conserv...