- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

A comprehensive analysis of the issues involved in planning for and facilitating successful street commerce Street commerce has gained prominence in urban areas, where demographic shifts such as increasing numbers of single people and childless "empty nesters, " along with technological innovations enabling greater flexibility of work locations and hours, have changed how people shop and dine out. Contemporary city dwellers are demanding smaller-scale stores located in public spaces that are accessible on foot or by public transit. At the same time, the emergence of online retail undermines both the dominance and viability of big-box discount businesses and drives brick and mortar stores to focus as much on the experience of shopping as on the goods and services sold. Meanwhile, in many developing countries, the bulk of urban retail activity continues to take place on the street, even as new car-oriented shopping centers are on the rise. In light of such trends, street commerce will play an important role in twenty-first-century cities, particularly in producing far-reaching benefits for the environment and local communities.Although street commerce is deeply intertwined with myriad contemporary urban visions and planning goals—walkability, quality of life, inclusion, equity, and economic resilience—it has rarely been the focus of systematic research and informed practice. In Street Commerce, Andres Sevtsuk presents a comprehensive analysis of the issues involved in implementing successful street commerce. Drawing on economic theory, urban design principles, regulatory policies, and merchant organization models, he conceptualizes key problems and offers innovative solutions. He provides a range of examples from around the world to detail how different cities and communities have bolstered and reinvigorated their street commerce. According to Sevtsuk, successful street commerce can only be achieved when the private sector, urban policy makers, planners, and the public are equipped with the relevant knowledge and tools to plan and regulate it.

Frequently asked questions

Information

CHAPTER 1

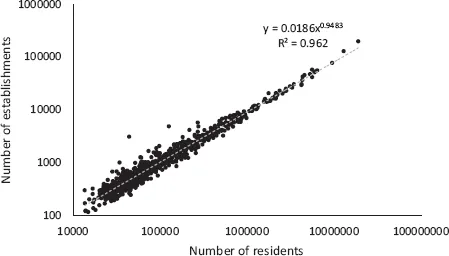

The Predictability, and Unpredictability, of Street Commerce

Different Scales of Street Commerce

# | NAICS | Description |

|---|---|---|

1 | 4411 | Automobile Dealers |

2 | 4412 | Other Motor Vehicle Dealers |

3 | 4413 | Automotive Parts, Accessories, and Tire Stores |

4 | 4421 | Furniture Stores |

5 | 4422 | Home Furnishings Stores |

6 | 4431 | Electronics and Appliance Stores |

7 | 4441 | Building Material and Supplies Dealers |

8 | 4442 | Lawn and Garden Equipment and Supplies Stores |

9 | 4451 | Grocery Stores |

10 | 4452 | Specialty Food Stores |

11 | 4453 | Beer, Wine, and Liquor Stores |

12 | 4461 | Health and Personal Care Stores |

13 | 4471 | Gasoline Stations |

14 | 4481 | Clothing Stores |

15 | 4482 | Shoe Stores |

16 | 4483 | Jewelry, Luggage, and Leather Goods Stores |

17 | 4511 | Sporting Goods, Hobby, and Musical Instrument Stores |

18 | 4512 | Bookstores and News Dealers |

19 | 4521 | Department Stores |

20 | 4529 | Other General Merchandise Stores |

21 | 4531 | Florists |

22 | 4532 | Office Supplies, Stationery, and Gift Stores |

23 | 4533 | Used Merchandise Stores |

24 | 4539 | Other Miscellaneous Store Retailers |

25 | 4541 | Electronic Shopping and Mail-Order Houses |

26 | 4542 | Vending Machine Operators |

27 | 4543 | Direct Selling Establishments |

28 | 7223 | Special Food Services |

29 | 7224 | Drinking Places (Alcoholic Beverages) |

30 | 7225 | Restaurants and Other Eating Places |

31 | 8111 | Automotive Repair and Maintenance |

32 | 8112 | Electronic and Precision Equipment Repair and Maintenance |

33 | 8114 | Personal and Household Goods Repair and Maintenance |

34 | 8121 | Personal Care Services |

35 | 8123 | Dry Cleaning and Laundry Services |

36 | 8129 | Other Personal Services |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. The Predictability, and Unpredictability, of Street Commerce

- Chapter 2. The Survival of Individual Stores

- Chapter 3. How Stores Cluster

- Chapter 4. Coordinated Clustering: Business Improvement Districts, Co-ops, and Malls

- Chapter 5. Location, Location, Location: How Retailers Gravitate to Homes, Workplaces, and Pedestrians

- Chapter 6. How Urban Design and Building Typologies Affect Retail Location Patterns

- Chapter 7. How Demographic Shifts and E-Commerce Are Reshaping the Retail Landscape

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Notes

- Index

- Acknowledgments