![]()

1 Base-of-the-pyramid markets and the need for frugal innovation

Introduction

Poverty is not just a lack of money; it is not having the capability to realize one’s full potential as a human being.

Base-of-the-pyramid (BOP) markets are mass markets in developing countries where at least four billion people, despite low disposable incomes, are inclined to buy new products to improve their everyday lives (Banerjee & Duflo 2011; Pitta, Subrahmanyan & Tomas Gomez-Arias 2008; Prahalad 2012; Tiwari, Fischer & Kalogerakis 2016). Developing and emerging countries such as India, China, Brazil, South Africa or Indonesia have these mass markets who need product innovations related to basic health, food and water, housing, sanitation and/or education needs (Alkire 2002; Cadeddu et al. 2016; Prahalad 2009).

Offering new market opportunities, Western and emerging market firms such as General Electric, Godrej and Boyce, Tata Group and Jaipur Foot have been tapping into these under-served billions of BOP consumers (Agarwal et al. 2017; Govindarajan & Trimble 2013). These firms have also faced significant challenges in altering products, practices and processes to suit these markets (Prahalad 2012; Simanis 2012; Subramaniam, Ernst & Dubiel 2015; Winter & Govindarajan 2015). One particular reason for this is BOP consumers do not necessarily want cheaper and simplified premium products, as often thought; they generally have preferences for better, pricier and more suitable products and services to address their needs (London 2016; Nakata 2012; Subrahmanyan & Tomas Gomez-Arias 2008).

To reach these consumers, modern new product development (NPD) trends are emerging from these firms’ practices. The literature discussing one of the most relevant NPD approaches in these new socio-economic contexts in developing countries1 points to frugal innovation (e.g. Pisoni, Michelini & Martignoni 2018; Radjou & Prabhu 2014; Rao 2014; Weyrauch & Herstatt 2017). Frugal innovation aims to develop new products characterised by their affordability, usability, durability and core functionality, which offer alternative solutions to existing products that are incompatible with BOP markets’ needs (Petrick & Juntiwasarakij 2011; Weyrauch & Herstatt 2017).

A well-known example illustrating the suitability of frugal innovation NPD for BOP markets in developing countries is Godrej and Boyce’s ChotuKool, an alternative to standardised refrigerators that are generally too expensive and unsuitable for Indian BOP consumers. The ChotuKool cooling device is highly suitable to these consumers as it is affordable (nearly 70 USD) and can store food and water for up to seven days without electricity. The ChotuKool is also portable, allowing transportable fresh water in rural areas, and fits into Indian BOP consumers’ houses (Agnihotri 2015; ChotuKool 2014).

The success of these frugal innovations’ NPD not only comes from their performance and suitability to local BOP markets but also stems from these firms’ different approaches to the NPD process (NPDP). In particular, this study highlights that these successful NPD in BOP markets is reliant not only on a firm’s ability to provide such innovation, but also on different NPD management practices throughout firms’ NPDP (Cunha et al. 2014; Pisoni, Michelini & Martignoni 2018; Radjou & Prabhu 2015; Zeschky, Winterhalter & Gassmann 2014). The next section discusses how frugal innovation and the NPDP are two fields that, when connected, clarify on the key decisions, tools and techniques necessary for the NPDP of frugal innovation, addressing BOP consumers’ needs.

NPD process (NPDP) and frugal innovation

The main question has shifted from why firms should innovate to how to innovate and adapt practices to the socio-economic context of developing countries. These alterations generally occurring in the context of innovation management practices emphasised firms’ NPDP as one of the most influencing factors for successful NPD (Barczak, Griffin & Kahn 2009; Markham & Lee 2013). Trott (2012) reinforced this, arguing that effective management practices have a critical effect on the direction and likely efficiency of firms’ processes. Actually, many studies have defined best-practice NPD as inclusive of NPDP aspects (e.g. Barczak, Griffin & Kahn 2009; Cooper 2013).

Yet while such NPD practices are well-researched, these studies have generally occurred in the context of high-income markets in developed countries. This leads to most well-established NPDP models integrating theories and practices based on high-income market contexts that are not necessarily suitable to guide firms innovate for BOP markets in developing countries (Le Bas 2016a; Radjou, Prabhu & Ahuja 2012; Viswanathan & Sridharan 2012).

Many scholars (e.g. Prahalad 2012; Radjou & Prabhu 2015; Viswanathan & Sridharan 2012) highlight the necessity to modify firms’ traditional mindset when undertaking NPDP for BOP markets, including the process by which the innovation is “conceived of, executed, and delivered” (Petrick & Juntiwasarakij 2011, p. 24). Léger and Swaminathan (2007, p. 22) proposed “the innovation process could follow a different pattern in developing countries”. Frugal innovation literature suggests such NPD approaches are emerging from a market-driven process comprising cheaper, simpler and resource-constrained innovation activities (Cunha et al. 2014; Sehgal, Dehoff & Panneer 2010).

One of the main reasons suggested by Radjou and Prabhu (2014) is traditional NPDP approaches are “bloated Western innovation model[s] [that are] … wasteful and out of sync with market realities”, and in particular for BOP markets. Indeed, the NPDP for frugal products involves significant adjustments for these consumers’ needs. It includes products’ attributes and features as well as development, manufacturing and delivery processes, which challenge the argument that only de-featuring premium products addresses poor people’s needs (Anderson & Markides 2007; Pisoni, Michelini & Martignoni 2018; Sehgal, Dehoff & Panneer 2010).

Despite such assertions, little research has explored the NPDP for BOP markets in developing countries (Lee et al. 2011; Subramaniam, Ernst & Dubiel 2015). Correspondingly, Cunha et al. (2014, p. 2) asserted that “[p]roduct innovation in resource-poor environments is as old as creativity itself, but as an academic field it is nascent and immature”. Agarwal et al. (2017, p. 11) recently highlighted gaps between NPDP for BOP markets and relevant industry research:

The ambiguity in the prescriptive variables exhibits limited research focus on the innovation process and different means or approaches toward achieving the required product characteristics.

Within this context, this raises questions on whether the current body of knowledge provides sufficient guidelines for academics and practitioners to drive successfully the NPDP for frugal innovation in BOP markets. The following section discusses a promising NPDP framework for frugal innovation from two key research areas, which highlights the importance of NPDP as a management practices for successful innovation.

NPDP framework for frugal innovation

New contexts of innovation often destabilise firms’ conventional ways of innovating (Sharma & Jha 2016), as they are required to move away from well-known practices (Le Bas 2016a; Nobelius 2004). This is especially true when undertaking NPD for BOP markets in developing countries (Ernst et al. 2015; Nakata 2012). Some scholars support that if a firm is willing to address BOP markets’ needs, numerous changes must be considered at its NPDP level (Léger & Swaminathan 2007; Radjou & Prabhu 2014; Sharma & Jha 2016). For example, in comparison with NPDP for high-income markets, using traditional market research or relying on existing infrastructure is not appropriate when targeting BOP markets (Prahalad 2012; Ramamurti & Singh 2009).

As frugal innovation literature has an increasing prominence in the innovation management field, the need for further studies to examine concepts, theories and practices of frugal innovators’ NPDP has thus become evident. Few scholars (e.g. Radjou & Prabhu 2015; Viswanathan & Sridharan 2012; Zeschky, Winterhalter & Gassmann 2014) have given attention to how to manage the development of a frugal innovation, though there is poor research on the management of frugal innovation from a new idea to a final scalable frugal product structured around NPDP (Agarwal et al. 2017; Subramaniam, Ernst & Dubiel 2015). This underpins the focus of this study, including the focus on developing a NPDP framework for frugal innovation.

In this vein, Ulrich (2011, p. 395) suggests developing NPDP models by “focusing on what decisions must be made, and then consider what information, perspectives, and tools are most relevant to those decisions”. To help understand the decisions made and tools used by frugal innovators across their NPDP, a consolidated NPDP framework is built through existing conceptualisations of NPDP models and well-established cross-functional activities embedded within phases and stages. While this framework acknowledges existing holistic models, it is not supposed to be comprehensive; it leverages the most common NPDP stages only. This search has included literature in relation to firms’ NPDP decisions serving developed countries, related to product innovation management, R&D management, engineering and design, marketing and operation management.

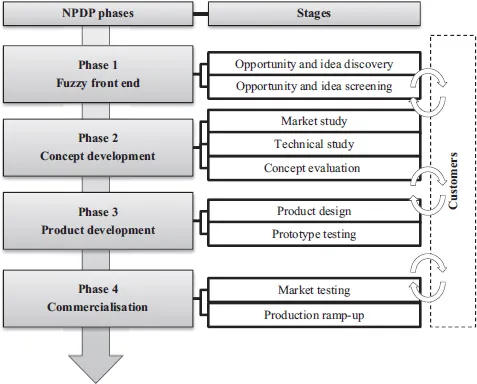

Figure 1.1 depicts the basis of this study’s consolidated NPDP framework upon which frugal innovation literature has been mapped out in Chapter 3. This consolidated NPDP provides a broad structure of the four NPDP phases and nine associated stages involved in the management of NPD to build the basis for the NPDP for frugal innovation. Chapter 3 provides more details about the stages characteristics, tools and techniques that portray the specificities of each stage.

Figure 1.1 Consolidated NPDP: four phases and nine stages

The use of tools and techniques was included as, in practice, these are not exclusive from decision-making such as decisions related to design (Lutters et al. 2014). The multidisciplinary character of NPDP is also observed across different activities, for example marketing activities at the market study stage, or engineering activities at the product design stage in Figure 1.1. Furthermore, the iterative nature of NPDP is represented by circulating arrows, allowing back and forth iteration as the most recent NPDP models suggest.

Chapter 3 will establish the basis for this study’s NPDP framework for frugal innovation, which is further explored through two Indonesian case studies in Chapter 4 and Chapter 5. To establish this NPDP framework, the frugal innovation literature is mapped on the consolidated NPDP. By mapping out the frugal innovation literature in the consolidated NPDP framework, the outcome is the development of 15 key frugal innovation practices to examine related to the decisions, tools and techniques preferred by frugal innovators. Frugal innovators in this study focused on those within developing and emerging countries, as these countries have often been observed as innovation hubs where such new products can emerge (Agarwal et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2011; Prahalad 2012). In particular, Indonesia is this study’s key focus due to its highly relevant settings detailed ahead.

Indonesia: a potential frugal innovation hub

Indonesia stands out as the largest economy in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and also ranks as the world’s tenth largest economy (based on Purchasing Power Parity, or PPP) (Asian Development Bank 2017; World Bank 2017e). Indonesia Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita was about 830 USD in 2002 and had risen to nearly 3,570 USD in 2016 (World Bank 2017b). Indonesia has moved from being a developing country to standing up as an emerging market due to shifting its focus on increasing the population’s well-being and seeking to become more industrialised (Amadeo 2018).

The economic growth illustrates not only the potential of this market, but also its innovation prospects. Indonesia is not without its own challenges either, being the fourth most populated country in the world with more than 260 million inhabitants (CIA 2017; World Bank 2017e) and more than 31 per cent still live on less than 3.20 USD a day (as per 2011 PPP) in 2016 (World Bank 2017a). Poverty is decreasing, however, with the population living under the national poverty line (below 0.82 USD) representing more than 43 million of the population (16.6 per cent) in 2007, decreasing to around 27.5 million (10.64 per cent) in 2017 (Central Statistics Agency BPS 2017; World Bank 2017c). While poverty is decreasing, the amount of people living under the national poverty line remains relatively high as well as the next level of ‘near-poor’ represent almost 40 per cent of the Indonesian population (approximately 104 million) (World Bank 2017a). This suggests that firms targeting the Indonesian BOP market should embed cost constraints in their NPD, which is a major characteristic of frugal innovation being affordable.

Furthermore, a high number of Indonesians who have low disposable income also encounter difficulties addressing their basic needs (UNDP 2015; World Bank 2017a). While the 16,000 islands that constitute Indonesian geography bring up complex problems of infrastructure (Prasetya 2017), another challenge is the large proportion of the population living in rural areas. These people account for approximately 45 per cent of the total inhabitants, according to the World Bank (2017d). In the aim to address rural and related problems such as difficult access to institutional and basic needs, the Indonesian Government implemented a development plan with a focus on education and healthcare issues related to those with low-income and living in rural areas (World Bank 2017e). This implies that the low-income and rur...