Southeast Asia begins where Northeast India ends.1

—NER Vision 2020 (2008:271)

Studying the sub-state region in international relations (IR) is a daunting task. The sub-state regions do figure in interstate interactions but barely get legitimate space for an independent enquiry due to the overt domination of the state-centric approach in the theoretical study of IR. The mainstream theories of IR do admit the ubiquitous role of sub-state region in interstate interactions; however, very little do these theories focus on it independently while explaining interstate behaviour in the study of international politics. In the process, sub-state region usually is relegated to a marginal position in the study domain of IR, as focus on national interests often supersede regional interest. Reconciling between the two and having a balanced approach for studying sub-regional cooperation across international borders remains a challenging task in the contemporary studies of IR in South Asia. Studying Indian foreign policy, more specifically studying the borderlands or border regions in trans-regional cooperation, is no exception. Here, a modest attempt is being made to explore a new frontier of enquiry in IR by taking up the interstate interactions involving present Northeast India – a geopolitically sensitive distinct region of India, strategically positioned at the confluence of South, East, and Southeast Asia. Historically, Northeast, which was a colonially created frontier region of British India, became a part of independent India through the nationalist struggle for independence. After the partition of British India, it has acquired a distinct regional identity, with historical, ethno-national, and geopolitical traits within the Indian Union. The region is surrounded nearly 98% by the international borders of China, Myanmar, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Nepal in postcolonial time, leaving only the narrow 2% land corridor with mainland India at Siliguri of North Bengal. Hence, the region can be termed at best as a ‘bordered region’2 or sub-state region of India – a geographically distinct region due to its peculiar position, encircled by five neighbouring states.

Purpose of the book

The primary purpose of the study is to explore how state actors shape geography of a sub-state region as well as place the region in a trans-border dynamics of conflict and cooperation matrix. The study intends to apply IR theory to understand state behaviour and subsequent impact upon the sub-state system by specifically focusing on India’s Northeast and its interactions with the neighbouring countries, particularly China, Myanmar, and Bangladesh, in the context of India’s Look East3/Act East policy.4 In other words, the study attempts to trace the geopolitical influences in shaping the sub-state region of Northeast India and its position in transnational interactions through the lens of IR theory – essentially focusing on the role of ‘state actors’. The study seeks first to examine the role of geopolitics and national security in shaping a sub-state region and its subsequent impact upon Northeast India (from a perspective of the Realist understanding of IR); and second, to assess the status of transnational interaction – i.e. Look East – through Northeast India (from the perspective of Liberal understanding of IR), and its implication upon the sub-state region in trans-border interactions with the neighbours. Highlighting the limitations of both the realist and liberal views, the study tries to situate the sub-state region within the emerging framework of ‘region-state’5 by adopting the constructivist world view to transform India’s Northeast frontier from the present geopolitical imprisonment to a robust trans-border region-building process.

Why IR theory?

Theories are useful tools to make sense of an unfamiliar terrain of study area. This is particularly relevant in studying social sciences. Even applying common sense to a particular domain to understand certain phenomena, the theory eventually guides the researcher’s action. If theory is used consciously and systematically, it can give better understanding to the study area with better application of theory to judge its strength and weakness. In IR, the word ‘theory’ facilitates understanding, analysing, and predicting certain phenomena of international events and their outcomes.

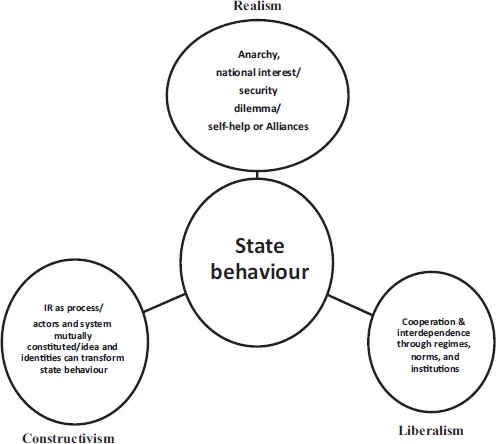

While explaining IR theoretically, a generic question arises: Does the structure of the system (international system) shape actors’ behaviour (states), or do actors (states) shape the structure of the system (international system)? Figure 1.1 indicates three important theoretical views of IR to comprehend the study area, i.e. realist, liberal, and constructivist views. Realists view national interest, i.e. defending national security through power, as a prime mover/driver of interstate relations in an anarchic international environment (Morgenthau 1948). The later variants of realists believe that the nature of the international system, i.e. states’ behaviour, is determined by the existing structure of power, which is normally known as Structural realism (Waltz 1979). On the other hand, liberals view behaviour of the actors (states) as determining the international system. They believe actors (states) are essentially cooperative. Anarchical environment can be mitigated through state-to-state cooperation by developing international regimes, norms, laws, institutions, etc. Through the promotion of economic integration and interdependence among the states, even in an anarchical environment, political antagonism can be overcome. (Nye 2007a; Keohane 1984; Rosecrance 1986). However, the constructivists take a middle path by rejecting power politics. According to the constructivists, actors (state behaviour) and system (international norms) are mutually constituted, and ideas (separate from power) are important in shaping international relations. For them, whether IR takes place in an anarchical system of states (realism) or a legally ordered society of states (liberalism) is a function of divergent and convergent national identities (Wendt 1992). Alexander Wendt, through his classic ‘agent-structure problem’, attempted to reconceptualise the relation between agents (states) and structures (international system) while discussing agency and structural determinism in international relations. He believes since structure contains ideational and material elements, and agents (state) and structure (system) are mutually constituted, possibly agents through agency can transform the system or be capable of making a difference in the system. One of the main assumptions of the constructive approach is that states, identities, norms, culture, etc., play an important role in the international system. Identities and interest of states are not simply structurally determined (as realists believe), but rather are produced by interactions, institutions, norms, and cultures. It is a process, but not the structure which determines the manner in which states interact. Constructivists believe that the meaning and construction of material reality is dependent on ideas and interpretations where state identities and inter-subjectivity play an important role in determining the outcome of state behaviour in the international system. Constructivism provides both a useful critique and an important supplement to the main theories of realism and liberalism. Though sometimes loosely formulated and lacking in predictive power, the constructivist approach reminds us of what the two main theories of realism and liberalism often lack. Constructivists help us to understand how preferences are formed and knowledge is generated prior to the exercise of instrumental rationality. In that sense, constructivist thought complements rather than contradicts these two mainstream IR theories. It believes in pluralism and does not always rely on state centricism.

Figure 1.1 Understanding state behaviour and interstate interactions (system) through IR theories

Northeast India as a sub-state region

The present Northeast India is an important strategic region as well as a land corridor of India to the East and Southeast Asian regions. The region’s social, cultural, and psychological bonding with Southeast Asia is a product of long historical traditions and interactions. It covers an area of 2,62,179 square kilometres, constituting 7.9% of India’s total geographical areas (Census of India 2001). The region represents a unique place, a meeting ground of many civilisations from both the Indian subcontinent and the Southeast Asia region. Almost all the Indian states of Northeast share ethnic ties with the adjacent neighbouring countries, particularly Myanmar, China, and Bangladesh. A home for 39 million people, constituting about 3.8% of the total population of India where 68% live in Assam (NER Vision 2020 2008: 4), the region is marked by its diverse people of culture, religion, languages, and dialects. The present-day Northeast also represents a confluence of many ethnic identities6 and competing ethnic aspirations that is distinct from mainland India. This distinctiveness places Northeast in a unique geographical and political space with a distinct regional identity. However, there is little understanding about the present complexities of Northeast India at both the national and international levels. The region is practically isolated from mainland India and from its neighbouring countries due to the introduction of a new notion of boundary and sovereignty in the postcolonial state-making process. As Van Schendel argues in his book Bengal Borderlands (2005), the partition of India was a patchwork that created new notions of boundary and created new barriers fragmenting not only two dominant cultures, i.e. Indic and Islamic, but many more ethnicities that were always at the margins of colonial state-making process.7 Northeast is a victim of such a state-making process, resulting in the complete physical and economic isolation from the both ends.

The partition of British India essentially made Northeast India a territorially trapped region with severance of natural transportation routes, market access through sea routes, and the cultural exchanges between the hills and plains populations. Most importantly, it has lost its route to Chittagong Port which is traditionally the gateway for the region to the East and Southeast Asia. The region had been at the forefront of trade and commercial intercourse in the colonial time with the establishment of industries of tea in 1835, an oil refinery at Digboi in 1890, and coal in the late 19th century. Coal was carried through the sea route and inland railway network of Assam Bengal Railway with a connection of potential mining sites in Assam’s frontier. The railway network that existed in the 19th century between the cities of Dibrugarh and Chittagong was an example of such a communication network of the colonial economy.8 The overall economic performance of the region was quite impressive during the colonial time.9 In the postcolonial phase, however, the geopolitical containment of the region from mainland India and its neighbours along with the militarised ethno-space has caused immense structural damage to the pre-colonial practices of trade, commercial intercourse, and cultural exchanges that existed in a non-territorialised contiguous space.

The partition of British India not only made the region economically backward but also effectively introduced a dependence economy in the region.10 Ironically, in the Nehruvian era the planned development model with a ‘top-down’ bureaucratised and centrally determined planning system did not pay much economic dividend to the region. In fact, wide economic disparities and inequalities have been witnessed in the region by replacing the native egalitarianism. A new political elite/class, based on patronage and power, has emerged in the region, appearing to be subservient to aspirations of nationalising frontier space. Subsequently, the postcolonial Northeast is confronted with a variety of challenges from within its own historicity as well as from ethnicities, from the centre due to the non-addressal of the region’s burning problems and non-recognition of sufficient regional autonomy, and also from the external-geopolitical challenge emanating from the neighbourhood, especially from Bangladesh, Myanmar, and China. All these factors contribute towards political instability and economic underdevelopment, posing challenge to the Indian Union from the borderlands.

Although India’s Look East/Act East policy has been in practice for more than a decade and a half, its benefits to Northeast in terms of economic and infrastructural development remain insignificant. At present, nearly one-third of India’s trade volume is with the ASEAN countries, yet it has no significant impact on the economic development of Northeast India. Logically, the Look East policy must place Northeast in the forefront of interactions between India and Southeast Asia, as the region provides the land corridor to connect the Southeast Asian neighbours. However, it appears that the Look East policy has had no definite impact upon the region and its trans-border interactions with the neighbouring Southeast Asian countries to date. Consequently, Northeast continues to remain an imprisoned land, from both mainland India as well as its international borders.

Framing the research questions

In the academic discourse, so far as Northeast is concerned, no serious attempt has been made to study the region from the IR perspective and to understand the sub-state region and its trans-border interconnections – be it conflict over border or trans-border economic activities within the framework of emerging sub-regional cooperation. Therefore, the present research takes up the study of the sub-state region of Northeast India from the IR perspective with the following assumptions: firstly, geopolitically sensitive border plays a crucial role in increasing interstate conflict and impeding cross-border economic cooperation; and secondly, the colonial legacy of Northeast as a frontier is still operative in the domain of Indian foreign policy, and the region continues to be imprisoned from mainland India and its neighbours, despite having potential of trans-border cooperation. On the basis of these hypothetical positions, the study puts forth the following research questions in order to understand the interaction between the sub-state region Northeast India and its neighbouring regions: How is frontier transformed into an international border with the development of a sovereign territorial state system? Do IR theories explain interstate behaviour over borderland – be it the conflict or trans-border cooperation? How is the sub-region of Northeast India transformed from a British frontier to a ‘bordered region and acquired a distinct regional identity’? Do geopolitics and national security of realist state strategies play a crucial role in making the sub-state region of Northeast India a bordered/securitised zone between South Asia and Southeast Asia? Can the Look East/Act East policy integrate the sub-state region of Northeast with the greater Southeast Asian region through promotion of trans-border interactions and economic cooperation? Where does the future of the sub-state region of Northeast India in the prevailing scenario of geopolitics as well as in the wave of sub-regional cooperation lie? Based on these central research questions, the study seeks to understand the role of the sub-state region of Northeast India in the domain of transnational interactions from the perspectives of IR.

Explaining the method

The study is undertaken from the perspective of IR with the positivist tradition of social scientific enquiry (systematic and verifiability of principle). It has both epistemological (philosophy of knowledge, i.e. how we come to know) as well as methodological (specific ways that we use to understand and explain certain reality/phenomena) components for explaining the sub-state region of Northeast India in interstate interactions (geopolitical influences as well as trans-border econo...