The age of bundan and haigaishugi

It seems to be important to focus on the concepts of bundan (division) and haigaishugi (exclusionism) for understanding Japanese society in the late 2010s. While I outline the genealogies and definitions later, social phenomena and changes that can be understood by using these concepts have frequently occurred. Asahi Shimbun, one of the representative nationwide newspapers in Japan and one known for its relatively liberal tone, began an irregular series of articles titled “bundan Sekai (The divided world)” in 2016. Since then, the number of articles including the word bundan in Asahi has increased.1

In addition to the quantitative change, an analysis of how the word bundan is used in the articles in Asahi Shimbun reveals the qualitative aspects of the change.2 Bundan is an ordinary Japanese word frequently used in everyday life. For instance, in natural disasters, the destruction of infrastructure, such as roads, electricity and gas lines, and the isolation of residential areas are often reported by the media with the word bundan, as in “raifu rain no bundan (destruction of lifelines).” In 2016, in articles on the Kumamoto Earthquake that occurred in the western part of Japan, the word bundan frequently appeared in Asahi. In addition, the election of Donald Trump in the U.S., the result of the referendum in the U.K. on the withdrawal from the E.U. and the hardship of evacuees from the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plants incident in 2011 (See Chapter 12) were reported with the word bundan. In more articles in 2017, the word bundan is collocated with the words “kakusa no kakudai (social and economic disparity)” and “kokumin (Japanese nation).” This means that in Asahi Shimbun, the word bundan is becoming more frequently used as a keyword to describe issues of social and economic inequality within Japan. The same tendency can be seen in the Yomiuri Shimbun, another representative nationwide newspaper known for its more conservative stance than that of Asahi. In Yomiuri, the word bundan tends to appear in articles describing international affairs more than it does in Asahi.3

However, even in the Asahi Shimbun, the application of the word bundan to describe domestic social issues is a relatively recent phenomenon. Most of the articles published before 2015 containing the word bundan, other than the articles on natural disasters, concern international affairs, such as China–Taiwan relations and the partition of North/South Korea (“nanboku-bundan”), or in contrast, conflicts among people in particular local communities in Japan. Other articles contain the term nanboku-bundan and describe Zainichi Koreans (Korean residents in Japan who migrated from Korea in the period of Japanese colonization and their descendants). In the 1980s, the word bundan was also used in the context of the Cold War, such as “tōzai-bundan (division of the Western (capitalist) and Eastern (socialist) countries)” of Germany.4

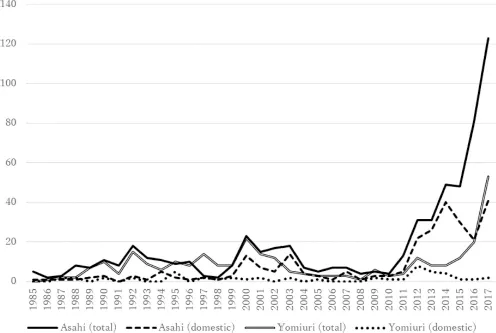

The Japanese word “haigaishugi” is less used in everyday life and appears much less than bundan in newspaper articles. However, as shown in Figure 0.1, while the word haigaishugi is used more often in Asahi than in Yomiuri, the number of articles including the word has increased in both newspapers since the early 2010s. The change is affected by worldwide trends—the rhetoric against migrants and refugees, ethnocentrism, terrorism and Islamophobia—and the emergence of populist movements in many countries are reported with the word haigaishugi in the Japanese media. In particular, the election of Donald Trump, “Brexit,” the “refugee crisis” and the strict policies for refugees in European countries led the number of articles including haigaishugi to increase, and domestic issues in Japan, such as hate speech movements, are treated as a part of the worldwide trend of haigaishugi.

While Yomiuri uses the word less often when referring to Japanese domestic social issues and trends, even in Asahi, which has a reputation for focusing on minority and discrimination issues, the word haigaishugi was rarely used to describe Japanese domestic issues and trends before 2011. The exceptions were articles on the scandal of the racist speech known as “sangokujin hatsugen (a speech that was discriminatory towards so-called ‘third-nation’ people, namely Koreans and Chinese)” given in 2000 by Shintaro Ishihara, the governor of Tokyo who was notorious for his extreme right-wing position, and the speeches on “Kitachōsen basshingu (North Korea bashing)” in 2003, both of which were reported and criticized as cases of haigaishugi in Japan.

Figure 0.1Number of articles including the word “haigaishugi”

Since 2012, articles in Asahi Shimbun using the word haigaishugi to refer to domestic social and political issues have increased. Various factors are related to the change. Shinzo Abe, known for his right-wing position in the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, became Prime Minister again and adopted an nationalistic political stance; territorial issues, such as the conflict with China over the Senkaku Islands, have deteriorated; and historical revisionism especially dealing with issues such as the comfort women emerged and became a point of conflict with Korea. The decisive reason was, however, that articles on hate speech movements mainly targeting Zainichi Koreans rapidly increased in 2012 (see Chapter 3). Zainichi Koreans are a symbol of the increasing tendency of haigaishugi in Japan. The increase in articles was influenced by the publications of journalist Kōichi Yasuda and sociologist Naoto Higuchi, both of whom researched Zainichi Tokken o Yurusanai Shimin no Kai (Zaitokukai: The Citizens Group That Will Not Forgive Special Privileges for Koreans in Japan), the largest hate speech group in Japan. Since then, in articles of the Asahi Shimbun, the word haigaishugi has often been used in relation to the hate speech issue, and the word has gradually come to describe domestic social issues in Japan. Other foreign residents are also the target of hate speech movements, although there are fewer articles written about them. Additionally, the “Tsukui Yamayuri En” incident of 2016, in which a man killed 19 residents with intellectual disabilities (see Chapter 11), and the “bashing” of Renho, the President of the leading opposition party the Democratic Party of Japan who was suspected of having dual nationality (Taiwan) and whose qualification as a member of the House of Councilors of the National Diet was questioned in 2017 (see Chapter 6), were reported as cases of emerging haigaishugi. Therefore, in Asahi newspaper articles the word haigaishugi has come to refer to various social issues contemporary Japanese society is facing.5

In this book, we see bundan (division) as a crucial characteristic of contemporary Japan and aim to examine the process of the emergence of haigaishugi (exclusionism) in a divisive society. However, as shown above, both the Japanese words bundan and haigaishugi have a relatively short history of describing domestic social issues in Japan. In fact, other words, such as “kakusa to fubyōdō (economic disparity and inequality),” “sabetsu (discrimination),” racism or nationalism, can be used to express our research interests. However, we prefer to use the words bundan and haigaishugi because they can be conceptualized differently from other similar concepts, and in the construction of the theoretical framework, we can create more appropriate perspectives to examine minority issues in contemporary Japanese society. In this Introduction, I will conceptualize bundan and haigaishugi based on a review of the related literature mainly written in Japanese, while a more comprehensive English-language literature review will be presented in Chapter 1.

The genealogy of bundan

As I have already examined, until the 2010s, the word bundan was seldom used to describe domestic social issues in the mass media. However, some scholars and journalists used the word to characterize contemporary Japanese society. For instance, in 2001, Kang Sang-jung, Atsushi Sugita, Junichi Saitō and Tetsuya Takahashi used the word bundan in the subtitle of their coauthored book published by Iwanami Shoten, a representative academic publisher known for its liberal position (Kang et al., 2002). Kang argued that bundan is the key word for understanding the world and global politics after 9.11 (Kang et al., 2002, pp. 3–8, 15–19). As Saitō and Sugita emphasized, the borderline in global geopolitics closely connects with the borderline within a nation state and the widening gap between the rich (global elites) and the poor (underclass) (Kang et al., 2002, pp. 53–67). Kang, Saitō, Sugita and Takahashi discussed the possibility of a “politics without borders” to resist the geopolitical and domestic politics of bundan (Kang et al., 2002, pp. 65–114).

While their discussion was full of macroscopic and enlightening perspectives, it is interesting that these leading political thinkers/theorists of contemporary Japan understood the concept of bundan from two correlational aspects. First, they saw bundan as the realization of the “Clash of Civilizations,” a famous thesis raised in the 1990s by Samuel Huntington, known as a prophet of the war on terrorism between the U.S. and Islam, although this thesis can be seen as a “self-fulfilled prophecy” in terms of the results of U.S. military operations (Shiobara, 2017). The concept disseminates the view that proponents of Islam are absolutely evil and their culture is incommensurable (Hage, 2017).

Second, Kang, Sugita, Saitō and Takahashi also saw bundan as the widening of the socioeconomic gap and inequality in a nation state due to globalization. Ryūichirō Matsubara, an influential economist of the University of Tokyo, also used the term bundan with this meaning in his book bundan sareru Keizai (The Divided Economy) published in 2005. He criticized the neoliberal structural reform (kōzō kaikaku) promoted by Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. Matsubara argued that the reform was very beneficial for the upper class of Japanese society, but the benefits never “trickled down” to the lower class. According to Matsubara, the Japanese economy became divided between the upper class, and large companies that benefited from the “Bubble (booming)” (often referred to in Japanese as the “kachi-gumi (the winners)”), while others suffered or the (“make-gumi (the losers)”) (Matsubara, 2005). A more detailed analysis and the consequences of the neoliberal reform in the Japanese context will be reviewed in Chapter 1 of this volume.

In his book bundan sareru Nihon (The Divided Japan) published in 2006, Takao Saitō, a renowned journalist, also criticized the neoliberal reform of the Koizumi LDP government that fostered economic and social inequality. He argued that not only economic opportunities, but also social citizenship of “make-gumi” were being denied. In other words, Saitō emphasized that not only the Japanese economy but also Japanese civil society is being divided as a result of the neoliberal reforms. To support his claims, he focused on the following examples: the ubiquitous installation of surveillance cameras on Japanese streets, the government’s establishment of the resident ID system, and the zero-tolerance policing of criminals and underclass people (see also Chapter 1). He insisted that these policies would divide citizens between “the watchers” and “the watched.” In addition, Saitō suggested that this new brand of nationalism would exclude particular categories of citizens an d violate their rights in the name of “national interests,” and this relates to the conservative push to amend the Japanese Constitution (Saitō, 2006).

Saitō also worried about the widening disparity in relation to educational opportunities for lower-class people. On this topic, the sociologist Tōru Kikkawa proposed the concept of “Gakureki bundan Shakai (a society divided by people’s educational background)” to describe the uniqueness of class formation in Japanese society after the Second World War. Academic and social debates on “kakusa-shakai (or a society with a large socioeconomic gap)” in Japan emerged in the 2000s. Within this debate, various issues were discussed, such as the increasing relative poverty rate and the increasing number of “working poor” or households on social security, the inequality between regular (full-time) and irregular employees, and the intergenerational income disparity and inequality caused by the education system. In his book published in 2009, Kikkawa argued that a crucial factor explaining the socioeconomic gap in Japan is “gakureki bundan-sen (dividing line based on people’s educational background)” between high school and university graduates (Kikkawa, 2009).

In his recent book titled Nippon no Bundan (The Division of Japan) (2018), Kikkawa aims to define the concept of bundan as distinguished from that of social class or social stratification. According to him, bundan has four characteristics: (1) increasing clarity the border among the groups, (2) immobility or fixed membership in each groups, (3) diminishing relationship between the groups and (4) unequal distribution of wealth and power between the groups. In particular, on the third characteristic, Kikkawa argues that in the situation of bundan, the life course of members in one group does not intersect with the life course of those in the other group, and that members of different groups do not communicate with each other in everyday life. As a result, they cannot socially imagine the lives of the people in other groups (Kikkawa, 2018, pp. 26–28).

In addition to Kikkawa’s argument, the word bundan was used by other sociologists to depict the inconsistency between people who suffered intensely from the widening social gap, and those who were relatively untouched or benefited from the reforms. Yuki Honda, an influential sociologist at the University of Tokyo, emphasizes the impact of “sengo nihon-gata junkan moderu (the circulation model of postwar Japanese society)” (Honda, 2014, 2015). She defines the model as the combination of bulk hiring new graduates, the promotion by seniority and lifetime employment system, the sexual division of labor, the great burden children’s education is for ordinary Japanese households, and government’s diminishing provision of social security for families. While this system assisted the economic development in postwar Japan, it has become dysfunctional since the 1990s, and as a result, dividing lines (bundan-sen) according to generation, gender, class and region have emerged (Honda, 2015). Honda suggests that bundan-sen refers to the inconsistency of interests between people of different categories (e.g. male and female, youths and elders, irregular and regular employment), as well as an antagonism towards people of other categories, who are often referred to as “the winners” or “violators of our rights/benefits.” Behind this antipathy, Honda also suggests this sense of insecurity and powerlessness is a consequence of the dysfunction of the circulation model of postwar Japanese society spreading throughout Japanese society.

Eisaku Ide, an economist/sociologist focusing on public finance studies, and hi...