![]()

Part I

![]()

1 Totalitarianism and political religion

Theocracy and integralism, authoritarianism and totalitarianism

Due to the key role “religion” plays in its investigations, one school within the history of politics, sometimes known as the Political Religion School, is of particular interest to us. Before discussing the premises and fallouts of this school, I will situate its most characteristic term, viz. “totalitarianism”, to the terminological context of the history of religions.

Throughout history, up until the birth of modern societies, ruling bodies (chiefdoms, monarchies, and so forth) have been based on religious politics.1 They regularly manifested themselves in the shape of theocracy, meaning that the dominant political discourse and the principal authorities were framed in religious terms and legitimated through mythic narratives and sacred inaugurations. In ancient and mediaeval societies, theocracy typically took the shape of sacred kingship: pharaohs were present as Horus incarnated, Norse kings traced their descent back to Odin, Chinese emperors ruled with the “mandate of Heaven” and Christian monarchs were appointed by the Grace of God.2 Ideally, societies seized a strictly hierarchical form (derived from hierós, sacred, and árchein, rule) as theocracies delegated significant powers to religious specialists (priests, Brahmins and the like) who guided and controled as the lieutenants of a divine legislator far out of reach for ordinary individuals.

A related form of religious politics could be called integralism.3 This form revolves around the belief in the societal need for a single, overarching ideology. In pre-modern societies, integralist ideas were expressly manifested through concepts fusing the notion of the inevitable, physical laws of nature – regulating everything from superlunary celestial bodies to sublunary falling apples – with the notion of ethico-social legislation. This fusing gave rise to generic concepts designating “order” (Egypt. ma’at, Gr. kosmos, Skr. rta, Pali dhamma, Chinese dao) that blurred the distinction between nature and man-made culture, and consequently curbed social criticism. We should also include as a product of integralist rhetoric the ethico-hygienic discourse on purity and pollution that organises many cultures, notably the Indian caste system.

The distinction between theocracy and integralism corresponds roughly to two key terms in the political sciences. According to consensus, we should distinguish between authoritarianism and totalitarianism as two undemocratic tendencies.4 Whereas authoritarian regimes are content with pacified and obedient citizens, totalitarianism aims to control the consciousness of the citizens and to convert them to the ideology of the ruling party. Thus, or so the comparison could be made, authoritarian rulers from the pharaohs to Franco did not really care what the citizens believed, as long as society operated smoothly, while totalitarian leaders such as Theodosius I and Mao aimed for the hearts and heads of people.

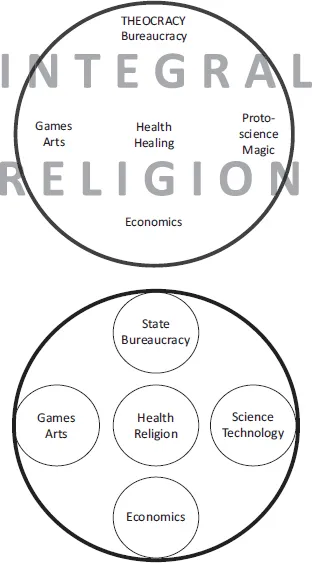

Granted that one of the characteristics of secular societies is the rise of more or less autonomous spheres (that is, economy, law, science, sports, and so forth) which are no longer governed by religious commandments but by their own logic, we could conclude that in modern societies, authoritarianism has taken over the task from theocracy of governing society with a firm hand, while totalitarianism is the modern tool for integrating all social spheres, as well as individuals, with the help of ideology (Figures 1.1a, 1.1b). In this chapter, I predominantly take an interest in “totalitarianism”, returning to authoritarianism and the relationship between the two in Chapters 3 and 8.

Political religion

In the 1965 revised edition of Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy, political scientists Carl Friedrich and Zbigniew Brzezinski suggested six criteria for the identification of totalitarian dictatorship.5 Since then, these criteria have piloted the study of totalitarianism:

- 1 An overall chiliastic, political ideology that promises “a perfect final state of mankind”.

- 2 A hierarchically organised mass party that comprises the top state apparatus.

- 3 A police force that terrorises people.

- 4 Party (state) control of mass communication.

- 5 Party (state) control of armed forces.

- 6 Party (state) control of the entire economy.

The first two criteria are of particular interest here. Carried into effect with religious overtones, the first criterion approaches what I have called integralism, while the second resembles what is denoted by theocracy. And indeed, since the interwar era, scholars, writers and journalists have asserted that totalitarian movements – whether of the fascist, Nazi or communist variety – have inherited the function of religious imaginary. Totalitarianism is claimed as an instance of religion.

Figures 1.1a, 1.1b Traditional versus modern secular society. The ideal traditional society (Figure 1.1a) is ruled by a theocracy and integrated as a coherent whole through the permeation of religious ideals and ideas. The ideal secular society (Figure 1.1b) maintains the autonomy of various spheres and thereby guarantees a civil society detached from the state.

This idea of a close affinity between totalitarian politics and religion has been the working hypothesis for what has been called the Political Religion School.6 This school is institutionalised around the journal Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, launched in 2000 and known since 2011 as Politics, Religion & Ideology.7 The defining feature of the school is exactly the idea that communism, fascism and Nazism are grounded in atavistic religious sentiments.8 Evidence in support of this idea is habitually based on proposed analogies between totalitarian movements and traditional religion. Expressions like the “the sacral socialist tradition” are typically lodged in these kinds of observations:9

Just as Moses led his people through the desert, so Lenin and Stalin have led the Russian working class to the Promised land… . Marxism, just like religion, required its discipline to be initiated… . Communism also became similar to religion by dint of creating a pantheon.10

Socialist and fascist ceremonies are presented within the school as “magical rites that led to trance and possession states”.11 Expressions such as “the indisputable fact that communism was never and nowhere free of quasi-religious elements” and claims that “communism took on para-religious forms on various levels” are common.12 Labels such as “communist religion” and “Bolshevik religion” seem uncontroversial.13 Even pronounced secularist and atheist movements are exposed as based on religious feelings; “vandalism of graves and the destruction of reliquaries” are seen as religious deeds.14

When it comes to communism, socialism and especially Marxism, the allegation regularly made is that historical materialism is a mythic narrative. It is thought to begin with paradisiac primitive communism and be advancing towards messianic fulfilled communism with class-struggle as the moral dynamo. The Marxist historiography is presented as “the battle between Good and Evil, proletariat and capital” and communists are said to “long for an inner-wordly salvation, a socialist paradise”.15

As far as I am qualified to judge, the Political Religion School has contributed substantially to empirical explorations and to the religion and politics nexus, not least by simply taking the attractiveness of what they label “political religion” seriously. As a continuation of the seminal work of historian George L. Mosse and his “cultural turn” in the study of Nazism, the mission of the Political Religion School is valid and valuable.16

However, I find the terminology of the school misleading and, as I aim to demonstrate, there are better terms which could be put into circulation. We must also approach the questions of unsound comparison methodology and the rather apparent political bias of the school. But first, let us look more closely at how the members of the school build their cases.

Comments on methodology and terminology

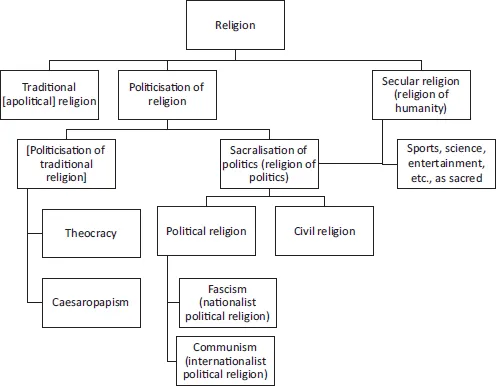

According to the Italian historian Emilio Gentile – together with Hans Maier and Roger Griffin, the leading scholar within the school – the concept of “political religion” is apt for revealing the important and constitutive aspects of totalitarian forms of ideologies and regimes (Figure 1.2). In the extensive manifesto-like article for the new journal in 2000, Gentile begins:

That the sacralisation of politics was an important aspect of the various totalitarianisms is not merely demonstrated by the historical reality of the movements in question, or by their markedly visible characteristics, dogmas, myths, rituals and symbolisms. It is also confirmed by the importance given to these aspects by practically every scholar of totalitarianism during the interwar period, whatever their cultural, political and religious orientation. Indeed, most assessments broadly agree that the sacralisation of politics (variously defined as lay religion, secular religion, earthly religion, political religion, political mysticism, and political idolatry) was one of the most distinctive elements, if not the most dangerous, of the totalitarian phenomenon. This process takes place when, more or less elaborately and dogmatically, a political movement confers a sacred status on an earthly entity (the nation, the country, the state, humanity, society, race, proletariat, history, liberty, or revolution) and renders it an absolute principle of collective existence, considers it the main source of values for individual and mass behaviour, and exalts it as the supreme ethical precept of public life. It thus becomes an object for veneration and dedication, even to the point of self-sacrifice.17

Figure 1.2 Gentile’s terminology. It should be noted that he uses the terms with some inconsistency.

The exposure of religious traits in totalitarian ideologies functions as an explanation for its attractiveness. Behind the façade of secular totalitarianism we accordingly – as demonstrated by the standard articles in the school’s journal – find religious themes such as myths, rituals, apocalypses, soteriological promises, irrational cruelties and trials on heresy. Terms from the history of religions such as messianism, eschatology, apocalypse, chiliasm and Gnosticism have been introduced to understand twentieth century totalitarianism as well as contemporary variants of totalitarianism such as Chinese communism and Islamism. In fact, from the perspective of at least some of the Political Religion scholars, there exists an implicating continuation from twentieth century totalitarian politics up to contemporary “fundamentalism”, “Islamism” and “jihadism”.18 Consequently, they make use of the term “Islamo-fascism”, as well as “Muslim totalitarianism”. Moreover, national liberation movements in the Global South are pointed out as additional recent forms of “sacralisation of politics”.19

Contemplating texts from the school, the reader gets the impression that they are dealing with things truly atavistic. Historian Michael Burleigh talks of “pseudo-religious pathologies”.20 According to Gentile, the religious dimension is in fact “the most dangerous and deadly weapon in the totalitarian arsenal”.21 In the eyes of celebrated Eric Voegelin, the roots of Nazism are not only religious, but “satanical” and “Luciferian”.22 Upon encountering this kind of phrasing, all with even a minuscule critical sense will be curious about the background for this type of rhetoric and the research it cloaks. A review of the intellectual and ideological history of the term “totalitarianism” is called for.

Intellectual and ideological background

Like most scholarly terminology, “totalitarianism” has a history that does not only consist of high-minded contemplation.23 In interwar and Cold War polemics, “totalitarianism” was a crucible made to amalgamate the two big enemies of Western liberal capitalism: Nazism and communism, a.k.a. “Brown Bolshevism” and “Red Fascism”.24

The groundwork for the discourse on totalitarianism goes back, as is quite well known...