In contemporary American culture, comedy is a genre that often thrives on the transgression of boundaries.

– Christopher M. Leighton

Part 1 of this book examines and overturns two major dichotomies that have dogged the thinking about humor: The first dichotomy holds that humor is inherently coded liberal and that it is essentially an anti-authoritarian, disruptive phenomenon. According to this view, conservatism and orthodoxy are antithetical to humor. The second dualistic assessment relates to the moral distinction between “positive” and “negative” effects (or intentions) of laughter. According to this approach, laughter is either a positive expression of joy and goodwill or a lamentable manifestation of mockery, cynicism, and arrogance. As I will demonstrate, the reality of humor is too fluid and complex to be captured by such simplistic prescriptive norms. Therefore, a more flexible and responsive model needs to be developed to do justice to the slippery, contextual, and contingent nature of humor. Chapter 1 lays out a critique of the ideological paradigm of humor, concluding with the introduction of a non-binary system of classifications, my four-factor model of humor. Chapter 2 explores the moral paradigm imposed by the Christian theology of laughter, according to which laughter manifests itself in a “positive” or a “negative” register.

Is humor inherently liberal?

Statements linking comedy with a liberal, and particularly a subversive, mindset are legion. David Banatar, for instance, has pointed out that “it is because of humour’s subversive power that many a despot has sought to prohibit humor that mocks him or his associates” (34). Wylie Sypher wrote that “Comedy is a momentary and publicly useful resistance to authority and an escape from its pressures” (241–242). Similarly, Paul McDonald noted that “When we are in a humorous mode we are also more adept at thinking critically … making us more likely to challenge rather than acquiesce to the powers-that-be” (80). Gilbert Leung maintains that “Laughter can be seen as an irruptive displacement of being and creative sovereign moment that poses a challenge not only to law as understood in the widest senses of the word, but also to any matrix of laws, mores, traditions, values, identifications, etc. that may persist in unresponsive fixity” (276). The British anthropologist Mary Douglas thinks of jokes as “an attack on control” (149), and she insists that “all jokes have this subversive effect on the dominant structure of ideas” (150). This notion that humor has an innately liberating, anti-dogmatic tendency often shades into a perception of humor as essentially aligned with a liberal political stance. In his book The Revolution Will Be Hilarious, Adam Krause writes that “the path to tolerance and the path to laughter are identical” (22–23), insisting that “a comedic mindset can help us develop a more free and democratic society” (12). Even more politically explicit, Alison Dagnes maintains that

The philosophy of conservatism is incompatible with political humor but liberalism suits it quite nicely. Conservatism supports institutions and satire aims to knock these institutions down a peg. This doesn’t necessarily mean there is bias afoot, but it does mean there is going to be more left-leaning material than right. The very nature of satire mandates challenges to the power structure, targets across the board, and an ability to take a nuanced or relativist examination of an issue in order to make the joke, and this falls squarely into the tool belt of liberalism.

(KL 5–6)

In their different ways, all these sources suggest that political comedy (and beyond that humor in general) resists power and destabilizes authority, promoting instead modes of thinking that foster criticism, openness, flexibility, and emancipation – the hallmarks of liberalism.

At first sight, this view appears to have a lot going for it. For one thing, the majority of contemporary US comedians are self-identified liberals (Dagnes xiv; Day 5). Moreover, those who believe that humor is at home on the liberal side of the ideological spectrum must have felt vindicated by the presidential transition from Barack Obama to Donald J. Trump. On the one hand, there was the liberal Barack Obama, a politician with a real comical gift. For eight years straight, he was headlining the annual White House Correspondents’ dinners, delivering well-timed, snappy, cleverly funny monologues that can withstand comparison with the best contemporary comedians like Jon Stewart or Larry Wilmore. This talent has earned Obama the moniker “Comedian in Chief.” On the other hand, there is the curmudgeonly Trump, a Republican who angrily berates people who make fun of him and whose attempts at delivering a comical monologue have occasionally bombed.1

But not only does the liberal president (Obama) “win” in a direct comparison with his conservative successor (Trump) when it comes to comical talent, but it is further significant that the liberal opposition to Donald Trump expresses itself prominently through channels of comedy. Even before Trump was sworn in, he had been the target of ceaseless ridicule in various media. And once in office, the mockery of his personality, policies, and attitudes multiplied to the point where much of the opposition to Trumpism seemed to have taken the route of comedy, thus giving further support to the view that humor tracks liberal. In May 2017, the New York Times reported that “Mr. Trump was the subject of 1,060 jokes from the leading late-night talk-show hosts in his first 100 days in office – far surpassing the number of jokes other recent presidents attracted in their entire first year in office. There were 936 directed at Barack Obama in 2009, and 546 toward George W. Bush in 2001. Bill Clinton had only 440 jokes in 1993” (Deb).

Humor and change – does comedy make anything happen?

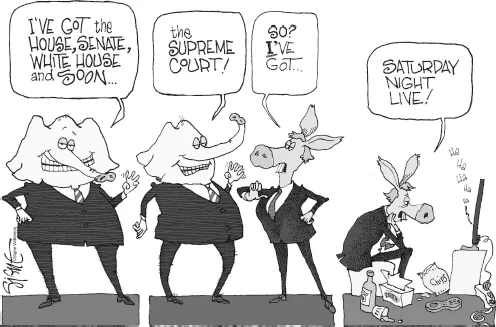

After Trump’s election, the widespread use of mockery and ridicule targeting him – from Alec Baldwin’s impersonation on Saturday Night Live to Stephen Colbert’s imitations on the Late Show – was intended to damage Trump’s public image and to undermine his political standing in the world. But has this strategy really paid off? To put it another way: Did the comical “united front” against Trump have any effect in furthering the interests of the anti-Trump coalition, either by discouraging Trump from taking certain actions, by softening his stances, or by forcing him to moderate his temper? One cartoonist suggests an answer (see Figure 1.1).:

Figure 1.1A humorous take on the effectiveness of political satire

This drawing by Signe Wilkinson humorously undercuts the supposed efficacy of humor as a valid change agent (see Figure 1.1).

But while it may still be too early to determine whether the comical attacks against Trump had any destabilizing effect on the president’s political agenda, it is also conceivable that they might have accomplished quite the opposite of their intended purpose. The real effect of the comical anti-Trump coalition may be to provide a safety valve, an outlet for the pent-up frustrations and anxieties of countless liberals who are shocked and exasperated by the political course that Trump’s administration has charted. Samantha Bee, whose show Full Frontal serves as one of the touchstones of the comical resistance to Trump, said in an interview she “was glad her show could provide an outlet for liberals’ frustrations” (Grynbaum and Koblin). Indeed, The New York Times described shows like Trevor Noah’s Daily Show and Samantha Bee’s Full Frontal as “cathartic” and referred to Saturday Night Live as a “comfort food franchise” (Grynbaum and Koblin). Comfort food is not known to fuel revolutions. So, it is quite possible that the wave of anti-Trump comedy has actually sapped some of the energy that could have been directed toward disruptive civic protests, thus acting as a palliative rather than as a fulcrum of resistance, ultimately making it easier for Trump to continue implementing his political agenda undeterred.

Humor and authority

The argument that politically subversive comedy may have a quietistic rather than activist-disruptive effect has been made in other contexts, and it is not a notion to be easily dismissed. For instance, Patrick Merziger’s work has turned up evidence that the Nazis actually encouraged people to make jokes about the government, hoping that it would defuse misgivings about the Nazi policies. At first, Germans seemed to be unsure of the risk they would run by telling Nazi jokes, and they tended to exchange them stealthily, hence the term “Flüsterwitz,” i.e. “whispered joke.” But it soon became apparent that the Nazi leadership not only did not persecute such jokes but actually encouraged them: “The ‘whispered jokes’ were welcomed by the regime, they were treated with goodwill and amusement, and they were understood as a token of affection from the people” (278). Merziger insists that “In contrast to this picture of a very dark and serious time [from 1933 to 1945], there were more laughs in National Socialism than ever” (281). The joke culture was approved even at the highest levels of the Nazi propaganda machine: “Institutions central to the public face of the National Socialists, including Joseph Goebbels himself, continually stressed the idea of the ‘whispered joke’ as posing no problem and that it could be permitted in daily life” (279). So, here we have a violent, authoritarian, right-wing regime that approved of people’s humor even in cases where the jokes were directed at themselves. In this situation, the Nazis either thought of humor as a wholly innocuous indulgence, i.e. incapable of inflicting real damage on the existing power structure; or, alternatively, they saw comedy as functioning like a safety valve, an outlet for feelings of anxiety and frustrations, thereby deflecting more subversive energies from manifesting themselves in specific acts of protest or civil disobedience. Whatever the case, Merziger’s research reveals that the Nazis apparently did not think of humor as dangerously subversive or critically liberal.

We are accustomed to think that those in power react allergically to manifestations of humor. The 2014 movie The Interview, starring Seth Rogan and James Franco, ridiculed North Korea’s dictator Kim Jong-un. The Dear Leader reacted with vitriol and barely concealed rage to this work, calling for the wholesale destruction of the United States in retaliation against the comedy. During the heyday of belief in humor’s disruptive potential, Foreign Policy reported enthusiastically in 2013 about “Laughtivism,” or the “strategic use of humor” (Popovic and Joksic) in conflictual situations, notably the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street. According to the authors, “laughter is a potent weapon” against corrupt state power and economic hegemony. Certainly, laughter can have this chastising, subversive, and humiliating function, just as Mark Twain believed it did when he famously stated that “against the assault of laughter nothing can stand.” The only problem with this line of thinking is that it can be taken to signify that all laughter has an anti-authoritarian function, as indicated by Popovic and Joksic: “Pro-democracy demonstrators around the world are discovering that humor is one of the most powerful weapons in the fight against authoritarianism.” It may well be that humor’s supposedly subversive effect mainly exists in the minds of those enjoying and supporting anti-establishment humor. But the inverse may also be true: i.e. that humor could be used as a tool to secure social and political conformism.

The function of humor under communism can serve as an object lesson in this regard. While Merziger’s research uncovered the function of humor in the Nazi era, Christie Davies has investigated humor’s role under Soviet communism. As far as Russian jokes about communism go, Davies’s research indicates that “even the members of the KGB enjoyed them” (Humor and Protest 305). Davies further elaborated on this observation: “It is doubtful whether for present purposes it is helpful to see the political jokes primarily as a weapon (Larsen 1980), as resistance (Zlobin 1996), or as a protective device for the recalcitrant (Waterlow 2013, 224); after all, even those who exercised power enjoyed the jokes (Deriabin and Gibney 1960; Myagkov 1976)” (“Political ridicule” 16). Davies thinks it is possible that in oppressive conditions “jokes are a safety valve that help oppressive regimes to survive and that it is counter-productive to try to suppress them” (Humor and Protest 300). Ultimately, Davies rejects the notion that jokes are politically instrumental: “It is extremely unlikely that, taken in aggregate, jokes have any significant effect one way or the other, particularly when compared with other stronger social forces… . Jokes are a thermometer, not a thermostat” (Humor and Protest 300). As an index of what is happening in a given society under an oppressive or incompetent regime, jokes may have a symptomatic function (acting as a thermometer), indicating how close to boiling point popular mood is. Other than that, “jokes are so feeble a social force that they can neither seriously undermine nor by acting as a safety valve prop up a political order” (“Political Ridicule” 14). In this view, humor is neither a driver of opposition nor a soothing agent to defuse protest but simply an indicator of the public mood or the mood of a certain sector of the public.

This brief consideration of the role of jokes in Nazi Germany and under Russian Communism is apt to raise doubts about humor’s inherent liberal or subversive functions. This line of inquiry can be extended by adopting an explicitly empirical approach. Indeed, why not ask actual liberals and conservatives how they feel about a number of jokes on a survey and then analyze the data using objective statistical tools? This is precisely what I have done in collaboration with a fellow researcher.2 In 2016, I conducted a humor appreciation survey to study the relationship between humor and religious belief. The survey was m...