![]()

Part I

RCEP, growth corridors in Asia and connectivity

![]()

1 The evolution of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

Deborah Kay Elms and Minh Hue Nguyen

In the beginnin

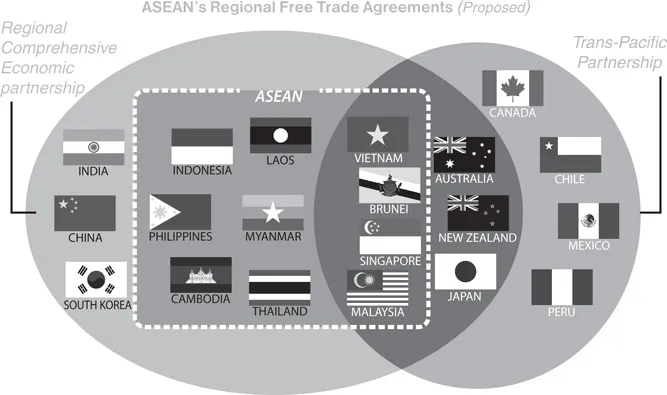

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) has grown out of five existing free trade agreements (FTA) with ASEAN. Meeting at the Seventh East Asia Summit in November 2012, RCEP was announced as a new trade agreement which would further the process of regional integration across 16 countries in Asia: Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam.

A dialogue for developing trade had been opened between ASEAN and its neighbours through the development of an ASEAN+3 track in 1996 with ASEAN, Korea, Japan and China. This ASEAN+3 process paved the way for Japan and Korea to argue for a common trade deal in East Asia. By 2005, Japan wanted to expand on the progress being made in trade agreements with ASEAN. ASEAN had begun working on FTAs with China in 2002, Korea in 2004 and Japan in 2005. All of these were signed and put into effect in 2005, 2007 and 2008, respectively, coming out of the ASEAN+3 dialogues. ASEAN also negotiated FTAs with India and Australia/New Zealand in 2004 that were signed and put into effect in 2010.

Shifting to regional agreements

Each of these ASEAN agreements, known as ASEAN+1s, moved Asia closer to having an Asia-wide integrated framework for trade. But the dream, pursued in different venues like the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and promoted by others in the region, called for deeper and wider integration.1 A patchwork of trade agreements can be difficult for companies to use, especially for smaller firms. Experts have labelled this problem the “spaghetti or noodle bowl” and companies have had to navigate often complex rules to take advantage of preferential rules under existing free trade arrangements. Since each agreement has different rules, paperwork and requirements, sorting out which provisions make the most sense for a company was becoming increasingly time-consuming. Firms were often opting to avoid using the agreements entirely, leading to low utilisation rates for many preferential trade deals.

At the same time, in the early 2000s, the World Trade Organization (WTO) was holding negotiations at the global level as part of the Doha Development Agenda (DDA). A breakthrough in Doha would have meant fewer reasons for regional trade arrangements. But as the years went by and the DDA continued to miss key opportunities, Asian governments increasingly focused on the prospects for renewed trade deals closer to home.2

Japan first proposed creating a wider Asia-Pacific free trade zone in the form of Comprehensive Economic Partnership in East Asia (CEPEA) in 2006. From 2006 to 2009, CEPEA’s proposal led to the grouping of ASEAN+6, which at the time was a loose collection of all of ASEAN’s free trade partners.3 This was seen as a strategic move to take the lead at developing a larger and more comprehensive economic zone in East Asia.

Since it seemed most Asian economies desired some kind of common Rules of Origin (RoOs) and many studies had identified these as a key factor hindering production costs,4 officials began looking for an agreement that would satisfy the desire for a regional multilateral FTA. CEPEA research by The Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) identified India, Australia and New Zealand as key partners in Asia-Pacific trade.5 Increasing links with these three would not only grow exports, but at the same time make the East Asian economies more resistant to shocks caused by problems in their own industries.6 In 2009, economic ministers in the East Asian Summit (EAS) agreed to consider carefully the impact of a regional trade agreement.

At this time, the idea of CEPEA was competing with the East Asia Free Trade Agreement (EAFTA), an ASEAN+3 led agreement specific to East Asia, (i.e. with only China, South Korea and Japan and ASEAN) with more specific provisions for their markets.7 However, since CEPEA also was a better fit within the objectives of APEC to create a Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP), it became easier to promote a larger grouping. ASEAN members seized the opportunity to repackage the idea, by consolidating CEPEA into an ASEAN endeavour to maximise ASEAN’s centrality as a hub and reinforce the importance of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC).

Consolidation into an ASEAN-Led RCEP

ASEAN had been pursuing economic regionalism as a tool for growth for decades. In 2007, AEC leaders identified their key goals moving forward—fully five years before the development of RCEP. The most important item on their agenda was “ASEAN centrality.”8 The regular meetings of the AEC and economic ministers (AEM) advanced the proactive development of ASEAN trade arrangements.

ASEAN officials pushed for the inclusion of India, Australia and New Zealand in RCEP, even when the East Asian nations feared this would dilute the quality of the agreement.9 It is important to note that nothing in the origins of RCEP points to the likelihood of RCEP being dictated or driven by China. Instead, from the earliest days, RCEP has been an extension of ASEAN+1 FTAs. China’s push for EAFTA, or an ASEAN+3 FTA, was, after all, not met with success.

As noted earlier, ASEAN had concluded five ASEAN+1 FTAs with Australia/New Zealand, China, India, Japan and South Korea by 2009.10 ASEAN was geographically placed at the centre of the CEPEA countries, but as the largest entity with existing agreements with all parties, could set the agenda for determining which provisions could be included in any regional agreement. While every potential member of the deal had links to ASEAN, not all had connections to one another. China and India, for example, had no existing trade agreement. ASEAN was, therefore, a strategic negotiating partner between ASEAN, the “Plus 3” countries, and the “Plus 6” countries.

In November 2012, leaders of ASEAN+6 nations agreed to launch RCEP, as a consolidation and advancement of trade integration objectives pursued under FTAAP, CEPEA and as a grand consolidation of ASEAN+1 FTAs.

ASEAN+1 FTAs

ASEAN therefore had a position of natural leadership for RCEP. Though FTAs did exist between other members of the grouping, the ASEAN+1 FTAs provided an easier common platform for launching negotiations. The benefits gained from ASEAN+1 FTAs between ASEAN and the other six nations could therein be extended to create a larger area, simultaneously opening up ASEAN as a hub and standardizing FTA provisions.

While many of the provisions in the ASEAN+1 agreements were similar across all five agreements, particularly for market access in goods, there was also fairly wide variation in each.11 Services and investment were incomplete in some, like the agreements with Japan, Korea and India.12 Only the deal with Australia and New Zealand could be fairly characterised as a comprehensive agreement, covering topics beyond just goods, services and investment and including topics like intellectual property rights and competition policy. Trade facilitation had remained general in ASEAN+1 FTAs.13 Straining the noodle bowl—or sorting out the overlapping and complicated RoOs used in different ASEAN agreements—was to be one of the most important tasks for RCEP.

Other bilateral FTAs between RCEP members like New Zealand and India had struggled to get off the ground for agricultural reasons.14 Indeed, just like at the WTO, agriculture within and between RCEP parties remained a sensitive issue. It was also expected to be problematic in the regional negotiations. Protectionist barriers remained high in many RCEP markets, with rising non-tariff barriers of various sorts in place.

Given that utilisation of the ASEAN+1 FTAs in 2013 was not high, it meant there was an opportunity for RCEP to improve on the status quo.15 The Leader’s Statement launching RCEP made important provisions for building off existing trade approaches outlined in the +1 FTAs. These base-building areas included “The General Agreement on Trade and Services (GATS) plus” components for services, investment opening and protection, and a general commitment to go beyond existing ASEAN+1 agreements. Most RCEP parties had, by 2012, engaged in various other FTA negotiations that included similar types of provisions, so there was reason to believe that getting a more comprehensive deal done in Asia should be achievable.

ASEAN-Led RCEP—a tough region for economic cooperation

RCEP was thus born as a regional experiment in coordination among 16 very diverse parties. The project and its negotiators began with a belief that coordination and the negotiation process had the potential to add significant value through synergistic negotiation efforts, the sharing of cost burdens between parties and the setting of high ambitions for quality outcomes.

High-quality outcomes could reconfigure the business environment, making it easier and less costly to do business in Asia. Larger regional agreements like RCEP held the promise of more useful trade rules than a collection of ASEAN+1 FTAs could achieve, since larger agreements were a better match for regionally integrated supply chains that dominate the member states.16

From the beginning, RCEP also had the potential to change political relations between members. ASEAN has been “in the driver’s seat” for the negotiating process. This has been a challenging position, however, to maintain, given ASEAN’s own institutional weaknesses and difficulties in arriving at common positions among ten quite divergent members.

Compounding the negotiating difficulties in reaching an agreement in RCEP has been the ongoing process in a parallel FTA, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Seven member countries in Asia are members of both RCEP and the TPP as shown in Figure 1.1 below. Balancing the demands of TPP and RCEP has required a delicate touch.

Several members (India, China and South Korea) are present neither in ASEAN nor in TPP. The strength of negotiating relationships that have been built-up across years are thus not as deep, nor are the country positions as well known with these three member countries.17 Of course, ASEAN had experience negotiating the +1 agreements with each partner country and some individual RCEP members, like China and Australia, had bilateral agreements in place between them. But overall, most of these experiences were not as long or as sustained as the ASEAN integration processes, nor as in-depth as TPP negotiations.18

China, as an example, appears to have seen negotiations in RCEP as an extension and formalization of a long history of relations with the South East Asian states. Even in the absence of RCEP, China has become the largest trade partner for nearly every member of the grouping. Hence, any additional trade benefits that flow from RCEP will likely solidify Chinese economic strengths in Asia—even if the final RCEP commitments are relatively weak.

Figure 1.1 Sorting out “The Noodle Bowl.”19

India has a more complicated relationship with RCEP. On the one hand, India has been following a “Look East” policy and what the then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh described as the “evolution of an open, balanced, inclusive and transparent regional architecture” with ASEAN.20 This approach, plus a strong desire to create a competitive, forward-looking domestic economy has pushed India to embrace part of the RCEP agenda, particularly centred on India’s traditional strengths in services. On the other hand, India’s difficulties in ensuring effective livelihood for farmers and problems with revving up the manufacturing sector have led to strong desires to keep out new imports from RCEP agricultural powerhouses like New Zealand and Australia and manufacturing giants like China or Japan.

The tensions within RCEP have proven challenging for ASEAN to manage. All participating states in RCEP are parties by virtue of their connection to ASEAN. RCEP negotiations take place in “rounds” with ASEAN negotiators central to discussions and negotiators from China, Japan, India, New Zealand, Australia and South Korea known as “ASEAN Foreign Partners” (AFPs). On the first day of negotiation rounds, all ASEAN members caucus separately from AFP members, who are not obligated to caucus concurrently...