demonstrate a “goodwill” towards the rest of the world that will result in a highly exceptional effect provided that … your propaganda apparatus can establish an extremely subtle and sophisticated format that then would be presented to the whole world. [He ended with the old Dutch saying,] “The cost precedes the benefit.”1

What could have been motivating a railway employee from a small Dutch agricultural town to make such an impassioned suggestion? Times had changed, for one, as the following discussion shows, just eight years earlier, World War II had brought nearly 350 years of Dutch control of the East Indies to a bitter end.2

The end of Dutch colonial rule in the East Indies, 1942–49

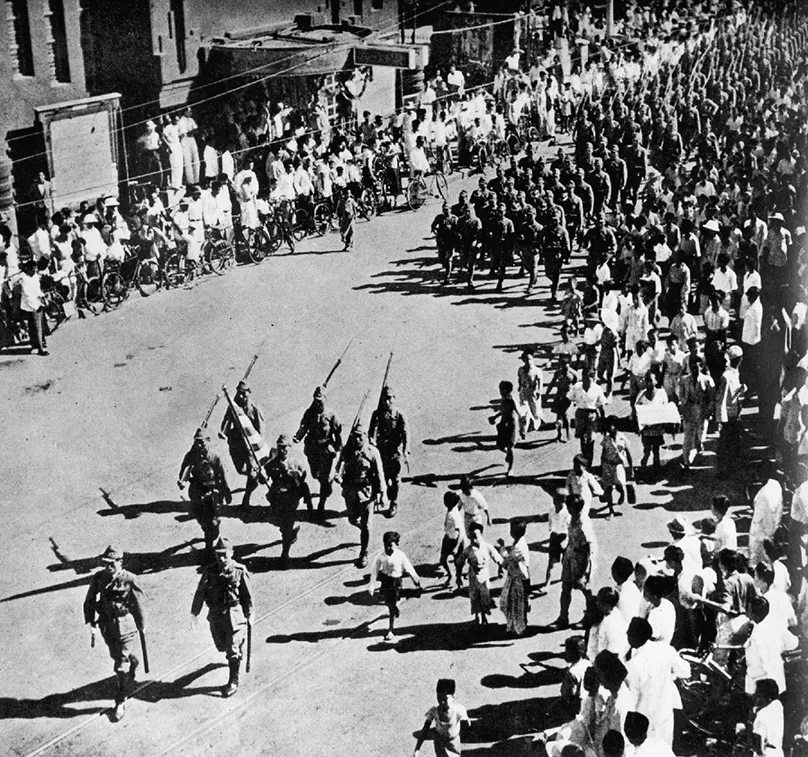

It began on January 10, 1942, soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese invasion and battle for the Indies lasted two months during which the Royal Netherlands Indies Army (Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger, or KNIL), as well as additional conscripts and Allied forces, were unable to defend the territory. Dutch forces surrendered on March 9, 1942, and the occupation would last for just over three years. Allied forces in Asia included Americans, British, Dutch and Australians, led by the British General, Archibald Wavell (1883–1950), tasked with defending the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, Burma and Thailand, which had also fallen to Japan. During the war, tens of thousands of European civilians and former soldiers were interned, or forced into labor, as Japanese officials sought to destroy “white prestige,” cultural influence and governance structures.3 With the capitulation, the failure of the KNIL to defend the colony made a lasting unfavorable impression on Indonesians. Under Japanese control, however, they were allowed to express what had been a suppressed nationalism in the inter-war period, and for the educated—including exiled nationalist leaders who were now freed—to attain high positions in the administration, concessions that were part of the Japanese strategy to secure local cooperation in the war effort.4

Figure 1.1 Japanese soldiers march through Batavia after the capitulation of the Netherlands East Indies government in World War II, March 8, 1942. National Archives of the Netherlands/Collection Spaarnestad/Photographer Unknown

Decades before the Second World War, Indonesian nationalism had emerged in the early twentieth century around a changing array of ideas and aspirations among Islamic groups, communists, and mass student associations.5 In 1912, for example, the Islamic League (Sarekat Islam, or SI) was founded by Muslim textile traders and soon expanded into a mass organization of over two million members. In 1920, the establishment of the Communist Association of Indonesia (Perserikatan Komunis di India, or PKI) alarmed Dutch colonial authorities and led to a crackdown on party leaders and agitators through forced exiles, imprisonments and “voluntary” emigrations. In 1927, as well, Indonesian students formed the Indonesian National Party (Partai Nasional Indonesia, or PNI), led by the charismatic Sukarno—known only by the one name as is traditional in Javanese culture—and geared toward mass solidarity and education for youths and adults. However, the PNI's larger goals included “the creation of one nation (Indonesia), one citizenship (Indonesian), one language (Malay), and, ultimately, Indonesian independence, none of which were to be obtained by cooperating with the Dutch.”6 In 1929, Sukarno and other PNI leaders were arrested as political threats, and the party disbanded two years later. The rising nationalist leaders Sukarno (1901–70), Mohammad Hatta (1902–80) and Sutan Sjahrir (1909–66) continued in the early 1930s to work toward an independent Indonesia. In early 1933, however, all activity perceived as subversive by colonial authorities was crushed on the orders of the Governor General, B.C. (Bonifacius Cornelis) de Jonge (1875–1954), in reaction to a mutiny staged by KNIL members on the cruiser, Zeven Provinciën. All Indonesian nationalists were arrested, and Sukarno, Hatta and Sjahrir were exiled to detention camps in the remote East Indies, where they were held until released by Japanese authorities in 1942. In the years following the crackdown, moderate Indonesian nationalists were more cooperative. Yet, throughout the decade before World War II Dutch officials rejected all political reform, even the mildest of proposals.7

For the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the loss of colonial rule in the East Indies, combined with German occupation at home, became a traumatic historical watershed.8 Yet, separation between metropolitan society and the colony during the war effectively increased the Dutch attachment to its colonial empire. In 1945, as war came closer to an end in Europe, there was widespread Dutch support for reestablishing colonial sovereignty in the East Indies. Despite an array of visions for reform—that had emerged across the political spectrum in the occupied Netherlands in the clandestine press, and in missives emanating from the Dutch government-in-exile in London—the coming end of German occupation in May that year turned the attention of Dutch leaders toward liberation of the East Indies in order to renew the country's colonial mission.9

For the Dutch railway employee in 1949, the biggest problem was not the end of colonial rule in the East Indies, per se, but rather, what had happened in the days and years following the war, since events on the ground quickly overtook discussions and plans for the colony. On August 17, 1945, two days after Japan's surrender to Allies, the popularly supported Indonesian nationalist leaders, Sukarno and Hatta—both of whom had been jailed in the inter-war period—unilaterally declared independence of the Republic of Indonesia.10 Hating Sukarno for having collaborated with the Japanese during occupation, Dutch officials refused to negotiate with him, preferring instead to meet with other nationalist leaders. However, Sukarno was appointed first president of Indonesia and held office from 1945 to 1967.

Figure 1.2 Sukarno after discussions with Sjahrir. Behind him, Mohammed Roem, November 15, 1946. National Archives of the Netherlands/Collection Anefo/NIGIS

The declaration of independence of the Republic of Indonesia by Sukarno and Hatta changed the course of events, upsetting especially Dutch plans for the East Indies. Having set their sights on establishing a Netherlands East Indies Civil Administration in the colony, Dutch officials rejected the declaration and refused to recognize Sukarno's authority and the new Republic.11 British forces, meanwhile, in late September, had landed in Batavia, the colonial capital on Java, and they soon began disarming and sending home Japanese troops, while also protecting Europeans and Eurasians who had been interned during the occupation. As Dutch and American troops slowly joined the Allied forces, they were incorporated under the command of British Lieutenant General Philip Christison (1893–1993). For his part, Christison allowed Republican forces to maintain their positions, and even to administer some territories in the absence of Allied control. At the same time, by late October 1945, revolutionary soldiers in the Indonesian People's Army, operating outside orders of the new Republic, had begun fighting Allied forces in east Java.12

In the Netherlands at this time, the Dutch parliament began debate on Indonesia and lawmakers affirmed the approach outlined by the Minister of Overseas Territories, H.A. Logemann, who declared the government's readiness to talk with “qualified” leaders in Indonesia, not Sukarno. To many Dutch leaders, Sukarno was seen as a traitor and a Japanese collaborator who deserved punishment for treason. While continuing to express a commitment to self-government in Indonesia, Logemann reinforced the idea that such autonomy would only take place within the wider Kingdom of the Netherlands, as declared on December 7, 1942, in a wartime speech by Queen Wilhelmina (1880–1962).13 Throughout 1945 and 1946, as well, as Dutch and Indonesian representatives began negotiating, any concessions officials attempted faced opposition at home. While the post-war political views on both sides were immensely complex, they can generally be understood in terms of a Dutch electorate determined to restore the pre-war colonial status quo, and an Indonesian nationalist republic demanding full sovereignty under Sukarno. In the Netherlands, any recognition of Sukarno and Hatta's independence declaration threatened Dutch lawmakers with massive popular disapproval at a period crucial to post-war reconstruction. At the same time, the Dutch hardline position risked setting off a resource-draining colonial insurrection, or worse, a full-scale colonial war.14

Figure 1.3 Queen Wilhelmina and Princess Juliana among soldiers, during a visit to Orange Haven (Oranjehaven), a club she established for Dutch exiles in London, September 11, 1944. National Archives of the Netherlands/Collection Anefo/Fotograaf Anbekend/Anefo

In May 1946, the new post-war Dutch government of Louis J.M. Beel (1902–77), of the Catholic People's Party (KVP), continued to reject recognition of Sukarno and his Republic of Indonesia. The Beel government negotiated with other Indonesian representatives, however. In early 1947, Dutch and...