This chapter aims to systematically outline the empirical and theoretical puzzles I seek to explain as well as the theoretical explanation I propose. To illustrate, I briefly contextualize the recent degradation of Taiwan’s press freedom in relation to Taiwan’s post-WWII history. Next, by systematically situating the Taiwanese case in the literature on human rights and press freedom, I then explain why existing scholarship is insufficient to account for it. Subsequently, I raise the book’s research puzzles by manifesting the paradox between the Taiwanese case and the dominant wisdoms from both comparative democratization and international relations perspectives. I elaborate my proposed theoretical explanation for press freedom’s evolution at the domestic and international levels, comprising the state’s economic role, economic dependence, and the four corresponding causal mechanisms. I also articulate the significance of the Taiwanese case and justify selecting Taiwan as the book’s focus. Moreover, I explain the applicability of the research approach (i.e. historical institutionalism), methods (i.e. multiple within-case comparisons and process tracing), and data (i.e. archives, interviews, and others) that I adopt to examine Taiwan in relation to the proposed theory.

Taiwan’s press freedom under China’s influence

Concerns have been growing about the potential impacts of China’s rise on liberal ways of life both in neighboring countries and the wider world. Take freedom of the press, for example. In America, Beijing blocked the Bloomberg and New York Times websites in 2012 due to their investigations into the large financial holdings of the families of Chinese leaders Xi Jinping and Wen Jiabao, causing both outlets to suffer great financial losses. In Europe, Chinese authorities spread China’s official view and encouraged self-censorship in film, art, and academic publishing by sponsoring newspaper supplements, promoting media cooperation agreements, and luring publishers with the Chinese market.1 In South Africa, one of the largest newspaper chains sold 20% of its stake to two Chinese government-linked entities in August 2013, increasing China’s control over local media in the region. In Cambodia, state-run media has tended to avoid reporting negatively about China since Cambodia began receiving considerable aid from China and its government formed a close relationship with Beijing.2 Recently, a new term “sharp power” was even coined by the US National Endowment of Democracy to represent the authoritarian influence with which China, as well as Russia, manipulate or distort information overseas, shaping public opinion and perceptions in targeted countries.3 In these circumstances, it is worth studying how the Chinese government stretches its media control beyond China’s borders. Taiwan, as a country in which China has particularly intense interest, is most likely to be the first affected should China exert its authoritarian influences abroad. Taiwan is, thus, a revealing case for examining China’s media control overseas, which deserves attention from broader academic and practical communities.

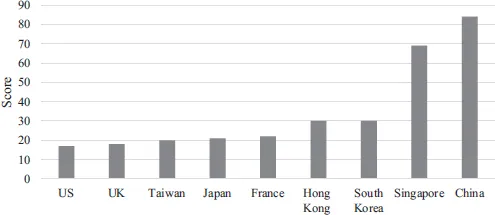

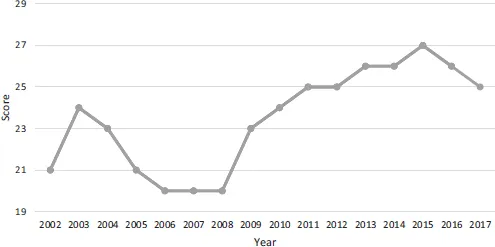

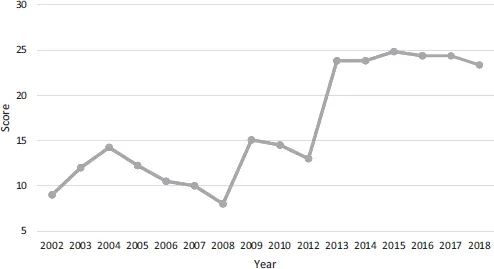

From a global comparative perspective, Taiwan is widely regarded as a successful third-wave democracy.4 However, Taiwan’s press freedom, which improved considerably from the late 1980s, is more recently considered to have begun eroding, starting from the late 2000s. Before 1988, Taiwan’s press freedom remained underdeveloped for over 40 years after World War II, as the press was actively repressed and muzzled under Kuomintang authoritarian governance. However, with press restrictions lifted in 1988 and a series of media liberalization policies implemented in the 1990s, Taiwan’s media freedom progressed significantly alongside economic liberalization and political democratization. As state power, which had controlled all aspects of society in the authoritarian era, was now curtailed by new democratic institutions, civil society as a whole enjoyed greater press freedom, though the public seemingly had less freedom to access complete information and mass media than private capitals, such as advertisers, media investors, and media conglomerates themselves.5 According to Freedom House,6 the level of Taiwan’s press freedom increased incrementally from the 1990s to the mid-2000s, then peaked in 2006–2008. For example, in 2008, Taiwan almost matched such old democracies as the US, the UK, and France. In East Asia, Taiwan was far ahead of another third-wave democracy, South Korea, and even slightly surpassed the mature democracy of Japan (see Figure 1.1). However, according to Freedom House7 and Reporters Without Borders,8 Taiwan’s press freedom has been deteriorating since 2008 (see Figure 1.2 and Figure 1.3). A particular concern is the “potential direct or indirect influence of the Chinese government on free expression in Taiwan” when the “commercial ties between Taiwan and mainland China deepened in 2010 with the signing of the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement.”9

Figure 1.1 Press Freedom Index, 200810

Figure 1.2 Taiwan Press Freedom Index by Freedom House

Figure 1.3 Taiwan Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders11

For instance, as a Taiwanese rice cracker maker basing its manufacturing and sales in China since 1992, the Want Want Group (旺旺集團) suddenly had a hand in the media market in Taiwan since the late 2000s, by purchasing the China Times (中國時報) in 2008, absorbing China Television (CTV) (中視) and Chung Tien Television (CtiTV) (中天電視) in 2009, and proposing to merge with China Network Systems (中嘉網路) in 2011. When growing into a cross-media conglomerate, it kept receiving subsidies from the Chinese government12 and started to accept embedded advertising from China’s State Council Taiwan Affairs Office (國務院台灣事務辦公室) and provincial/municipal governments.13 To protect its financial interests in China, the Group had a tendency to whitewash news and commentaries on the topics deemed sensitive to Beijing, such as the Tiananmen Incident (天安門事件), Tibetan or Xinjiang autonomy, and the Falun Gong movement (法輪功).14

Such a self-censorship phenomenon happened not only to pro-Chinese unification media, like the Want Want-China Times Media Group (旺旺中時媒體集團) but also to pro-Taiwanese identity media, such as the Sanlih E-Television (SET) (三立電視台). In particular, the SET started a business strategy to expand the sale of its Taiwanese dramas in the Chinese market in the late 2000s. The station not only strived to make its dramas accessible to Chinese audience via online video platforms such as Tudou.com (土豆網) since 2009, but it was also devoted to seeking approval from the Chinese authorities since late 2011 for its dramas to be aired on television in China. As a response to the request of China’s National Broadcasting Headquarters (廣電總局), the SET closed down the Big Talk News (大話新聞), a high-rating pro-Taiwanese identity, anti-Beijing political talk show in Taiwan for its business to go smooth in China.15 The examples of the Want Want Group and the SET revealed that Taiwanese media’s editorial autonomy and news diversity appeared to be eroding along with deepening commercial ties between Taiwan and China since the late 2000s.

The paradox of Taiwan’s press freedom

Many explanations have been provided regarding the condition and evolution of press freedom and other human rights. First, at the domestic level, the existing literature considers the state and the market as the fundamental determinants of press freedom. Some studies, drawing on classical liberalism, highlight the role of state power in determining the condition of press freedom. While authoritarian institutions enable state restrictions on the media’s free speech and activities through state ownership of the media,16 state control of economic resources,17 and state censorship,18 democratic institutions reduce state violations of human rights and press freedom through party competition,19 coordination among citizens under the constitution,20 and constraints on executive power.21 These studies may help to understand the underdevelopment of press freedom under the Kuomintang (KMT) authoritarian rule before 1988 as well as the improvements in media freedom along with the process of democratization after 1988. However, they are unable to explain why the public still had less freedom to access complete information and mass media than media companies themselves did when the media were already protected from state intervention under democratic institutions after 1988. These studies are moreover unable to explain why Taiwan’s press freedom started to be considered eroded after Taiwan experienced its second peaceful electoral alternations in 2008 which symbolized the consolidation of a nascent democracy from a comparative democratization perspective.22 Other research, taking market factors into consideration, is concerned about the potential impacts of corporate power on press freedom in a capitalist democracy through concentration of media ownership23 as well as profit-driven news biases that favor advertising providers,24 intended audiences,25 and media owners themselves.26 These studies may help to comprehend why the public’s full freedom to access unbiased information and mass media was still limited when media corporations were already relatively free from state control and operated under market mechanisms since 1988. However, these studies were still unable to explain the noticeable degradation of freedom of the press in Taiwan starting from 2008.

This raises the study’s domestic-level research puzzle: As Taiwan experienced political democratization and media liberalization from the late 1980s, state influences on press freedom were constrained while corporate influences persisted for two decades up to the late 2000s. Why did Taiwan’s press freedom progress steadily from 1988 only to suddenly decline from 2008 to the present? Are state power and corporate power sufficient to determine press freedom? If so, in what conditions do either of them enhance or diminish media freedom? If not, does foreign power play any role here? How do state power and corporate power interact with foreign power to influence press freedom?

Second, at the international level, and from the perspective of neoliberalism in internati...