Outline

On March 5, 1923, the morning edition of the Yomiuri shinbun (Yomiuri News) carried an article titled ‘Jidō no dokusho yoku to kinshi no hei’ (‘Children who read a lot risk short-sightedness’) (Anonymous 1923, p. 4).1 The editorial, submitted by an anonymous subscriber from Tokyo, warned readers of the adverse effects of small print used by Bunmeidō, an Osaka-based publishing company specialising in sokkibon (stenographical novels). ‘Didn’t the publishers know that the small print used in the pocket-sized novels was damaging to the eyes of the young?’ The author then launched a scathing condemnation of young people reading for pleasure. Instead of working, young ‘ruffians’ were taking up space on public trams indulging themselves in trite literature.

Our irate friend was referring specifically to the Tatsukawa bunko (Tatsukawa Library), a series of samurai novels and historical biographies, published during the Taishō era (1912–1926). These so-called novels were in fact transliterated versions of kōdan (classical narratives) rooted in the Japanese tradition of performative storytelling (Barbara Ruch in Ruch 1977, p. 286). Their author was Tamada Gyokushūsai II 二代目玉田玉秀斎 (1856–1921), a kōdanshi (classical storyteller) from the yose (vaudeville theatre). This monograph takes Tamada’s work published by Tatsukawa Kumajirō 立川熊次郎 (1878–1932) – owner of the Bunmeidō publishing company – as a focus for exploring key facets of the emergence of modern urban culture in pre-war Japan.

As indicated, the Tatsukawa bunko proved especially popular with young semi-educated readers (artisan apprentices, factory workers, labourers, and school-children). Collectively, this broad demographic was particularly vulnerable to the social inequities of the age. Frequently marginalised by society, these social groups are hard to locate in history. It is my hope, therefore, that in examining the series we might gain a clearer understanding of the literature’s place in Japanese cultural history and of the messages it conveyed to its audience.

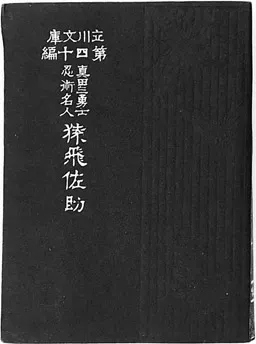

The materiality of the Tatsukawa bunko was exceptional, making it easy for anyone to identify any of the 190 or so works, even at a glance (Figure 1.1). The covers came in seven colours: deep red, cobalt blue, a lurid shade of yellow, olive green, black, indigo, and a rather fashionable shade of purple. The title of each jacket was embossed with crisp, white lettering; gilt edging decorated the spine (Figure 1.2). Inside, the books were equally lavish. Printed flowers roped together in spiralling patterns added another subtle dimension of colour before the colophon. But the crowning glory was a frontispiece by Hasegawa Sadanobu III (1881–1962), an acknowledged expert in contemporary ukiyo-e (lit. ‘pictures of the floating world’). Consequently, the books were highly prized as collector’s items (Figure 1.3).2

The chief protagonist of the Tatsukawa bunko is a fictional warrior named Sarutobi ‘monkey-jump’ Sasuke 猿飛佐助, vassal to the Toyotomi general Sanada Nobushige (1567–1615), more commonly referred to these days by his alias Yukimura. Historical evidence shows that there were established narratives within the kōdan community that mention Sasuke in connection with the Sanada clan from the 1880s onwards. For instance, a version of Sasuke appears briefly as a middle-aged warrior in Sanada sandaiki (Three generations of the Sanada: A Chronicle) published in 1888 (Ryūji 2004, pp. 300–301). This revelation has produced a great deal of controversy as to whether there was a real prototype for Sasuke or not.3

In 1960 a service was held in Osaka to celebrate the opening of a new museum dedicated to preserving artefacts from the city’s famous keep. Local historian Okamoto Ryōichi (1939–1988) worked on preparations for the event. Whilst cataloguing items located in the keep’s dungeon, Okamoto discovered an old manuscript from the eighth year of the Bunsei era (1818–1850) titled Shinsen jitsuroku taiheiki (Newly Selected Real-Life Accounts from the Tale of Great Peace).4 Further examination of the documents by Okamoto revealed that there was a person called ‘Sarutobi Sasuke’ hidden among the lists of Yukimura’s forces mustered at the ‘Summer War’ of Osaka in 1615. Sasuke’s rival Kirigakure ‘hidden-in-the mist’ Saizō 霧隠才蔵 also appears on the list of assembled warriors. (These events were recounted by Kitagawa Hiroshi (a local scholar) in the online edition of the Sankei shinbun in 2011; Minamimoto 2011, sec. Intabyū).

Figure 1.1 and 1.2 The original edition of Sarutobi-sasuke published in Osaka (1914). Bunmeidō used a diminutive form of 150 mm × 117 mm, something halfway between the Foolscap octavo (170 mm × 108 mm) and the Crown octavo (190 mm × 126 mm): both were standard book sizes during the 19th century

Takahashi Kei’ichi, a researcher working at Ehime University, heard of Okamoto’s discovery and was intrigued. Was it possible that two of Japan’s most celebrated fictional characters were real? And if so, why had they been mentioned in historical documents detailing the military campaigns fought by Japan’s national architect Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) during the Azuchi-Momoyama period (ca. 1573–1615)?

An expert in Edo literature, Takahashi decided to create a ‘genealogical study’ of the find. He found that the names of the two feudal mercenaries do indeed appear in the text. However, these references are hidden in the margins. They also use unfamiliar combinations of Chinese characters. Takahashi cites this as the reason for the historical oversight. Japanese scholars worked on a system of character adaption from very early on – hybrid works using variants of Chinese script exist from circa 596 CE, but the kana system of phonograms (written characters used to represent sound) that expressed local speech was not stable until the 9th century (Rabinovitch 1996, secs 2, 2.1, 3, 4, 4.1, 5, 5.2). The writing system has also undergone similar developments, hence the difficulty in verifying the two names. (For more, see Moretti 2010, p. 299.)

Takahashi takes this premise further. He argues that having seized power from the Toyotomi clan, the Tokugawa Bakufu (lit. ‘tent government’) banned any artistic interpretations associated with the historical event (Takahashi 2010, pp. 1–6). The measure was meant to prevent any seditious commentary that might cause another civil war. Given the draconian nature of censorship during the Edo era (1603–1868), Takahashi’s hypothesis is plausible.

Figure 1.3 Frontispiece showing Sasuke (bowing) before his teacher Tozawa Haku’unsai by Hasegawa Sadanobu III (1881–1962)

However, most scholars, critics, and fans of the Tatsukawa bunko accept Sasuke as a native literary adaptation of Sun Wukong, a monkey deity from the classical Chinese fable Xiyouji (Journey to the West).5 Thanks to the spread of Buddhism, the exuberant exploits of the mischievous immortal are common throughout Asia (Ohnuki-Tierney 1990, Meir 1992, Isobe 2011, pp. 212–229). In Japan he is known as Songokū. Like his transcultural counterpart, Sasuke possesses keen senses and great physical strength; he can also control the elements of fire and water using magic. There is one significant difference between the two characters: Songokū is an immortal, whereas Sasuke is not.

Tamada posits this fictional Sasuke as a proxy for Yukimura in a covert war fought against the Tokugawa clan. His journey ends with the Summer War of Osaka (1615), part of the Naniwa Wars (‘Naniwa’ is the old historical name for Osaka). During the last days of the conflict Ieyasu’s troops sacked the city, forcing the designated ruler of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyori (1593–1615), heir to Toyotomi Hideyoshi (ca. 1536–1598), to commit ritual suicide whilst the walls of Osaka Castle burned around him. Yukimura came to national prominence at this time as Hideyori’s guardian but died in the ensuing skirmish. Sasuke is supposed to have perished with him. After the carnage was over, Ieyasu saw that military and bureaucratic power was transferred to Edo. This tectonic shift profoundly affected local attitudes in the Kamigata region.

Mediated through the writings of Tamada, the Toyotomi clan and their associates (the Sanada) took on a subaltern hue. This is significant because Ichikawa Kōzō and Ozaki Hotsuki (1928–1999) have argued that contemporary audiences of the Tatsukawa bunko with an elementary level of education identified with Sasuke, mapping out new associations that resonated with their own longing for better living conditions. Juxtaposed with the political disturbances of the Taishō era, Sasuke’s desperate struggle for survival against greater forces took on new meaning. Initially this phenomenon was strongest in the industrial capital of Osaka, where the books were first published. Thanks to the success of the Bunmeidō series, this reading of Sasuke took hold nationally, only to become conflated with popular notions of the Minshū sōjoki (‘Era of Popular Violence’) that ran from 1903 to 1918.

Despite the controversy, all scholars concede that the Bunmeidō version of the tale Sanada yukimura san yūshi ninjutsu meijin sarutobi sasuke (Monkey-jump Sasuke: Three Renowned Ninja Heroes of Sanada Yukimura, 1914) remains the most influential account of the Naniwa Wars (Takahashi 2010, p. 6). But the narratives of the Tatsukawa bunko did little to challenge the notion that violence used to punish evil could be used for the social good; if anything, it accentuated the idea. These ‘hyper-masculine’ narratives were subsequently criticised by the press and politicians for encouraging anti-social behaviour and violence associated with anti-democratic movements, such as strike-breaking, criminality, and the like. Yet Sasuke’s reputation in the modern era remains untarnished, his recalcitrant nature cited as proof positive of his good intentions. It seems, therefore, that a mixture of cultural forces must be at work.

Contested territories

Print was initially the most powerful resource used to create the ‘imagined communities’ associated with the ‘nationalisms’ of Japan (Anderson 2006, chap. 6, Shimazu 2006, sec. Introduction). However, contemporary studies now question the perceived authority of text as a reliable and fixed source of information. As Adrian Johns states:

Any printed book is, as a matter of fact, both the product of one complex set of social and technological processes and also the starting point for another. In the first place, a large number of people, machines, and materials must converge and act together for it to come into existence at all. How exactly they do so will inevitably affect its finished character in a number of ways. In that sense, a book is the material embodiment of, if not a consensus, then at least a collective consent.

(Johns 1998, p. 3)

Narrative is also dependent on forces outside of an individual author’s remit. Time, place, and custom influence the production of any text, be it in the form of the spoken word, manuscript, film, or otherwise. Therefore, a work of art is not simply the product of a single imagination; it is a mediated response to a multitude of stimuli (Odagiri 2010, p. 202). Popular arts by their very natures have much to say about the culture that produced them (Desser 1983, p. 14). Accordingly, this work attempts to show that objects have their own complex histories and associations that linger, reform, and evolve – sometimes over centuries – to become powerful totems for certain groups within a society. It does so by highlighting the political and social complexities that existed in the realm of publishing during Japan’s industrial modernity.

During the first quarter of the 20th century, people in Japan felt politically disenfranchised. Since its formation in 1868, the Imperial Japanese State had been engaged in a protracted camp...